Forced to mask her true identity and instincts, Alexia begins her new life with Vincent, slowly learning how to take care of other people and how to let others take care of her as, under the weight of her sci-fi pregnancy, her body begins breaking down.

When Alexia is introduced, she is a child playing in the backseat of her father's car. Annoyed by the noises she is making, the man turns around to punish her and loses control of the vehicle, causing it to crash at the side of the road. Alexia, who was not wearing a seatbelt, hits her head against the window and is urgently brought to the hospital, where she has to undergo a surgical operation in which a titanium plate is welded onto her skull, leaving her with a gnarly scar and robbed of the innately human sense of empathy. "Watch out for any neurological signs," one of the doctors recommends the day of Alexia's discharge. Her mother and father both utterly fail to follow the advice, either because they are unable to recognize how differently their daughter is acting or because, to put it bluntly, they cannot bring themselves to care enough to notice. Their faulty parenting style, detached and unwilling to prioritize Alexia, is what brings to the catastrophic events depicted in the movie.

In the same way, Adrien's life too has been ruined by his father's inability to be a good parent: throughout the movie, it is hinted that the disappearance of the boy was caused by none other than Vincent, who was an inattentive father. The plot does not seek to give further information regarding what happened to the boy after he went missing: he is to be forgotten by all, even by the screenwriter.

Adrien is, in all senses and purposes, Alexia's mirror.

When Vincent picks Alexia, who is posing as Adrien, from the police station, a detective states that they are going to run a DNA test to guarantee that the person claiming to be the missing boy is, in fact, none other than the missing boy, Vincent stops him. "Think I can't recognize my own son?" he asks. It is left open for the audience to decide if the man was always aware that Alexia was tricking him, or if he deluded himself into thinking that the woman is actually his son. By the time he finds out, stumbling into Alexia fresh out of the shower and not yet wrapped in the oversized clothes that conceal her identity, Vincent declares that he does not care for her identity, or why she took Adrien's place: she is her son, and he loves her deeply.

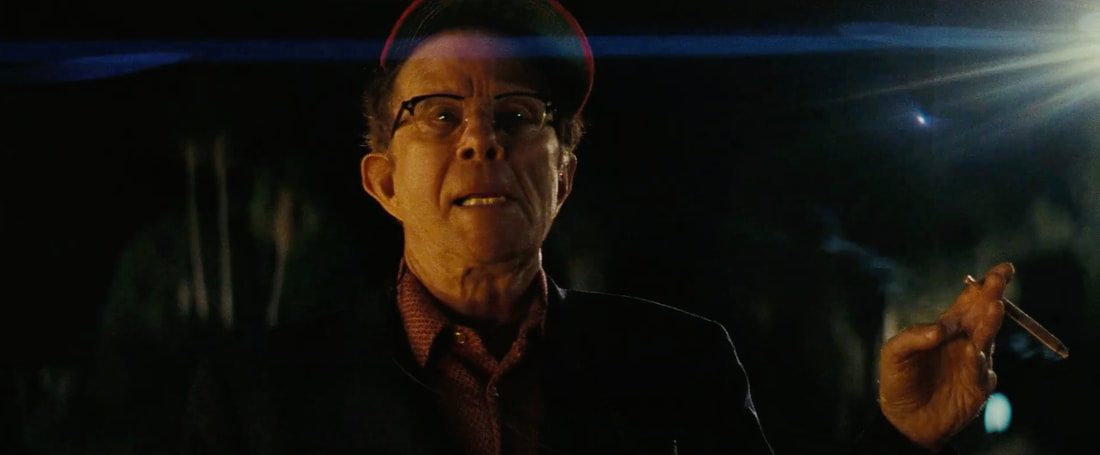

Finally offered this second chance at fatherhood, Vincent struggles to find a healthy place between his old and new ways. The old part of him inhabits the world of toxic masculinity: captain of the local firefighter station, he has become a gym rat with a steroid addiction in a desperate attempt to show the younger men that surround him that he is still superior to them, no matter how old he might get; while the new wants him to be soft-bellied, milk as milk, caring father he never was before. He wants to teach Alexia/Adrien how to shave their face, gives them a piece of titanium that will give their broken nose a more natural shape, employs them at the fire station and immediately ensures that the other guys will not pick on them for their weird looks and frail body, but also wants to keep his position of tough man.

In the world of Titane, women are ruthless serial killers always able to conjure back-up plans on the spot, and men are weak creatures who cower in front of difficult situations, unable to protect what they cherish the most, and haunted by the consequences of their own actions.

It is a story that depicts a desperate, incestuous kind of love, much like the one presented in Titane, in which the lines of what is acceptable and what is not are blurred. Per Ducournau's words, the baby Alexia conceived with the muscle car marks the birth of a new, monstrous humanity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed