Pan’s Labyrinth: Morality in Disobedience and Adulthood

By Nathan Rowe

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), by Guillermo del Toro, is a dark fantasy drama that follows a young Spanish girl as she comes of age in the aftermath of a war. Ofelia moves with her mother to the mill where her new stepfather, a leader of the oppressive Franco regime named Captain Vidal, is tasked with bringing to heel some freedom fighters living in the surrounding woods. Ofelia discovers a magical labyrinth and is tasked by a faun to complete three tasks to regain access to the magical underworld. The film features the Latin American tradition of magical realism, as well as del Toro’s blend of spiritual themes and creature design. Del Toro uses the magical and real aspects of the film to teach Ofelia about, and bring her into, womanhood. Ofelia discovers that adulthood brings an obligation to disobey, and to trust her sense of what is right in the face of injustice. While on her journey into adulthood Ofelia will see the adults around her follow their own sense of right and wrong, each teaching her a lesson about morality.

From the beginning of the film, del Toro’s symbolism shines through. We are introduced to Ofelia as a reader of fairy tales as she travels to a new home. Ofelia’s mother views her reading as childish, but the audience comes to learn that Ofelia’s love of fairy tales creates a connection to a magical world. Ofelia finds the missing eye of a statue with a gaping mouth and repairs it, thus allowing a fairy to come out of it. The film uses both eyes and mouths as motifs, symbolizing moral vision and greed for power. The gaping mouth is left behind once sight is restored, thus magic, symbolic of pureness, is able to reenter the world. In one scene within the first five minutes of the film, del Toro’s symbolism has conveyed all of the themes of the film, and Ofelia’s role of forcing those around her to act on what they think is right.

Ofelia’s other journey in the film, besides gaining and restoring moral sight, is to come into womanhood. She has two juxtaposed maternal figures, her own mother, Carmen, and the head maid of the house who is an ally to the rebels in the woods, Mercedes. Broadly, these two women represent a repressed femininity and an empowered femininity, though both are positive maternal figures for Ofelia in some aspects, and have something to teach her. Carmen represents a repressed femininity. This is expressed in several ways, including the way that she interacts with Ofelia and her new husband, Captain Vidal. Captain Vidal can be described as an oppressive force in the film, and this applies especially to his new wife, Carmen and her daughter Ofelia. We see that the oppression of Carmen’s femininity and independence come from her desire to please Captain Vidal. She sits in a wheelchair despite knowing she was strong enough to walk to satisfy Vidal’s desires, as well as tells flattering stories about her interactions with Vidal around the dinner table.

We see Carmen’s desire to please Vidal also in how she treats Ofelia. She is often kind to Ofelia, sleeping in the same bed as her and asking her to read stories to her unborn brother. However, the womanhood that Carmen attempts to bring Ofelia into is one in which Ofelia’s duty is to satisfy men. Carmen constantly comments on qualities of Ofelia that she is dissatisfied with, including Ofelia’s reading as an adolescent behaviour, and her unwillingness to call Captain Vidal her father. The most excited we ever see Carmen is the moment in which she is preparing to dress Ofelia up for a dinner party Captain Vidal is having. She states that the captain would be pleased to see her looking like a proper lady. Notably, we do not ever see a positive reaction from Carmen when Ofelia does wear the dress, that role is reserved for Mercedes, who compliments her, but does not do so in a way that implies Ofelia’s appearance is to pleasure a man.

From the beginning of the film, del Toro’s symbolism shines through. We are introduced to Ofelia as a reader of fairy tales as she travels to a new home. Ofelia’s mother views her reading as childish, but the audience comes to learn that Ofelia’s love of fairy tales creates a connection to a magical world. Ofelia finds the missing eye of a statue with a gaping mouth and repairs it, thus allowing a fairy to come out of it. The film uses both eyes and mouths as motifs, symbolizing moral vision and greed for power. The gaping mouth is left behind once sight is restored, thus magic, symbolic of pureness, is able to reenter the world. In one scene within the first five minutes of the film, del Toro’s symbolism has conveyed all of the themes of the film, and Ofelia’s role of forcing those around her to act on what they think is right.

Ofelia’s other journey in the film, besides gaining and restoring moral sight, is to come into womanhood. She has two juxtaposed maternal figures, her own mother, Carmen, and the head maid of the house who is an ally to the rebels in the woods, Mercedes. Broadly, these two women represent a repressed femininity and an empowered femininity, though both are positive maternal figures for Ofelia in some aspects, and have something to teach her. Carmen represents a repressed femininity. This is expressed in several ways, including the way that she interacts with Ofelia and her new husband, Captain Vidal. Captain Vidal can be described as an oppressive force in the film, and this applies especially to his new wife, Carmen and her daughter Ofelia. We see that the oppression of Carmen’s femininity and independence come from her desire to please Captain Vidal. She sits in a wheelchair despite knowing she was strong enough to walk to satisfy Vidal’s desires, as well as tells flattering stories about her interactions with Vidal around the dinner table.

We see Carmen’s desire to please Vidal also in how she treats Ofelia. She is often kind to Ofelia, sleeping in the same bed as her and asking her to read stories to her unborn brother. However, the womanhood that Carmen attempts to bring Ofelia into is one in which Ofelia’s duty is to satisfy men. Carmen constantly comments on qualities of Ofelia that she is dissatisfied with, including Ofelia’s reading as an adolescent behaviour, and her unwillingness to call Captain Vidal her father. The most excited we ever see Carmen is the moment in which she is preparing to dress Ofelia up for a dinner party Captain Vidal is having. She states that the captain would be pleased to see her looking like a proper lady. Notably, we do not ever see a positive reaction from Carmen when Ofelia does wear the dress, that role is reserved for Mercedes, who compliments her, but does not do so in a way that implies Ofelia’s appearance is to pleasure a man.

Carmen’s pregnancy is another aspect of her repressed femininity. We see that her pregnancy is making her sick, she gradually worsens as the film progresses. As her health worsens, Captain Vidal makes it clear on multiple occasions that he is less concerned for the wife that he married than he is for the son she is carrying. The film frames Carmen’s pregnancy in such a way that it seems more like a curse than a blessing, almost as if Captain Vidal has poisoned her with his child. This association is further exacerbated by Ofelia’s first trial, in which she must cleanse a tree in the forest of a monstrous toad who is living in its roots and poisoning it. The entrance in which Ofelia goes under the tree is vaginal in shape, and the branches of the tree resemble fallopian tubes. The tree and its poisoning by the greedy toad is representative of Carmen and her pregnancy. Vidal’s impregnation of Carmen, to serve his own ego and extend his legacy, has effectively poisoned Carmen (Perschon).

In contrast, Mercedes is a much more positive maternal figure for Ofelia. While Mercedes is the head of Captain Vidal’s household, we find that she isn’t serving the oppressive fascist, but rather using her position to aid in his downfall. Mercedes’ journey to bring down VIdal parallels Ofelia’s journey through her magical tasks. Mercedes steals the key to the food storage area to feed the rebels, and hides a knife in her clothes to defend herself if she is captured. Ofelia must retrieve a key and a dagger in her first and second tasks respectively. The key and the knife are both used by Mercedes to provide and protect, to continue life, and Ofelia has to make the decision not to use her knife to take life (Smith). Mercedes is more representative of the maternal aspect of protection than the physical aspect of maternity like Carmen. When Ofelia asks Mercedes to sing her a lullaby, Mercedes admits to only knowing one, and not even knowing the words. This isn’t a problem for Ofelia though, and doesn’t make Mercedes a less maternal figure, nor less of a woman.

The underworld of magic is largely symbolic of Ofelia’s journey into womanhood as well. Her first task from the faun is highly symbolic of Ofelia’s physical transformation into adulthood too, not just of Carmen’s pregnancy. Ofelia enters into a series of tight, tube-like spaces under a tree through a hole that is vaginal in shape. She has to leave the dress her mother gave her to please the captain behind, and kills the toad which was blocking the growth of the tree. This task is symbolic of puberty, something in both her body and the tree has changed and now both are able to grow, flourish, and “bear fruit.” The undergrowth of the tree being muddy and full of bugs is representative of the childhood or perhaps masculine view of the female anatomy, especially the menstrual cycle, as being gross or unclean. The toad who was blocking her growth into womanhood, can be understood to represent oppression of femininity, and its defeat as a feminine liberation. After she comes out from under the tree, she finds that the dress that she was meant to wear for Captain Vidal had been dirtied beyond presentability. This is symbolic of her newfound womanhood that requires her to reject the idea of her femininity being used to please men, and that her femininity is not a source of oppression. The oppressed femininity that her mother and Captain Vidal had tried to press onto her can not now be applied to her.

Del Toro also uses the aspects of the story that deal with Ofelia’s journey into womanhood to intertwine the magical and real worlds. After completing the first task, a magical book that was given to Ofelia by the faun bleeds in the shape of the female reproductive system, soon covering the entire page. While this is again symbolic of Ofelia entering adolescence, it is also more literally what is happening outside the door, as Carmen’s uterus bleeds and she stumbles around for help. The faun’s solution for Carmen’s sickness is to place a mandrake root under her bed in a bowl of milk and feed it blood. The mandrake being in the shape of a small human, and the two fluids being largely associated with the birthing process and being a mother are not coincidental. The magic seems to work as well, as Carmen improves greatly, until Vidal finds the mandrake. Carmen awakes for the first time in weeks as Vidal rages at Ofelia, representing Carmen’s motherly instinct. However, instead of defending Ofelia, Carmen destroys the mandrake root, and immediately goes into labor. The death of the mandrake precedes her death so closely that the audience knows that Carmen effectively killed herself by destroying it. The symbolism of Carmen destroying the root, a feminine symbol, in an effort to please Captain Vidal, and dying for it, is not lost on the audience. However, the mandrake root is evidence to the audience that the magical and real worlds are intertwined, and that the magical world is not just a figment of Ofelia’s imagination. The mandrake which was given to Ofelia by the faun clearly exists, as Carmen and Vidal both interact with it. The ability of the magical to affect the physical is also without doubt, as Carmen’s health improves while the mandrake is cared for, and fails so rapidly when the mandrake is destroyed (Smith).

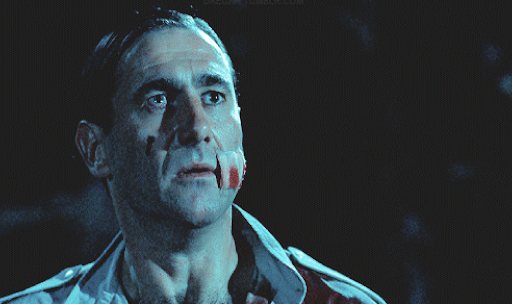

Captain Vidal is a character that represents absolute oppression, and this oppression is visible in the two main themes of the film, womanhood and moral responsibility. From the first scene he is in, Captain Vidal forces his wife to sit in a wheelchair, denying her the right to operate independently. Captain Vidal is overly concerned with his legacy, and is oppressing Carmen’s independence in favor of protecting his child inside her. He doesn’t care for her as a person, he is only concerned with something her body can do for him (Perschon). We see this as well in the dinner scene. Carmen tells a sweet and flattering story about how they met, and Vidal rebukes her in front of all of his guests. He then without hesitation stands for her as she leaves the table, forcing the rest of the guests to follow suit. This action is not the result of some hidden secret respect for her, but rather an example of Vidal’s pride. Though he doesn’t respect her as an individual, his ego requires her to be respected in regards to the part of her that she owes to him. He stands out of respect for her position as a Captain’s wife, his wife, forcing the rest of the guests to acknowledge her position as well. Vidal standing for Carmen’s exit is not a sign of respect for her, but rather a ploy to remind all of his guests of the power that he wields.

Captain Vidal is a character that represents absolute oppression, and this oppression is visible in the two main themes of the film, womanhood and moral responsibility. From the first scene he is in, Captain Vidal forces his wife to sit in a wheelchair, denying her the right to operate independently. Captain Vidal is overly concerned with his legacy, and is oppressing Carmen’s independence in favor of protecting his child inside her. He doesn’t care for her as a person, he is only concerned with something her body can do for him (Perschon). We see this as well in the dinner scene. Carmen tells a sweet and flattering story about how they met, and Vidal rebukes her in front of all of his guests. He then without hesitation stands for her as she leaves the table, forcing the rest of the guests to follow suit. This action is not the result of some hidden secret respect for her, but rather an example of Vidal’s pride. Though he doesn’t respect her as an individual, his ego requires her to be respected in regards to the part of her that she owes to him. He stands out of respect for her position as a Captain’s wife, his wife, forcing the rest of the guests to acknowledge her position as well. Vidal standing for Carmen’s exit is not a sign of respect for her, but rather a ploy to remind all of his guests of the power that he wields.

The captain is also a source of moral blindness in the film. The captain owns a broken watch that once belonged to his father, symbolizing his fear of death and his desire to extend his legacy. The care that he expresses for his son’s well being is not out of fatherly love, but rather an obsession with his own ego not unlike his interaction with Carmen in the dinner scene. His son is a symbol of his legacy, and for him to pass on his watch to his son would be his way of extending his life and legacy past death, as his own father did. We see an example of Vidal’s self-absorption when Vidal disregards the doctor’s concern for Carmen and says “A son should be born where his father is.” Several scenes represent Vidal’s immense pride, including the scene in which he murders a pair of farmers. Vidal simply looks bored with the questioning until the farmer’s son says “if my father says he was hunting rabbits, then he was hunting rabbits.” It is this phrase that sends Vidal to murder the farmers, not any evidence that he finds. This is due to the implications of the statement, that the farmer is deserving of some level of respect from Vidal, that he is honorable or important enough to be taken at his word. The idea that someone deserves Vidal’s respect is an affront to his pride, and sends Vidal into a murderous rage. Vidal’s obsession with hunting the rebels is another example of his immense pride. For someone to oppose him in the first place is an affront to his pride, but the fact that they continue to evade him speaks to an ineptitude on his part, an inability to punish those who disobey. The ridiculous brutality of this scene is an example of how Del Toro uses magical realism. The extremely dark scene is almost too gory to watch, and how casually Vidal treats the violence creates leaves the audience in shock. Vidal treats the violence as if it were normal, while the audience reels at something that is so out of the ordinary that it seems unreal. The brutality of the scene makes something that is firmly grounded in reality, Vidal and his violence, seem supernatural (Perschon).

The two characters that Ofelia sees as stand in parental figures, the doctor and Mercedes, also teach her the importance of moral disobedience. The doctor kills one of the rebels out of mercy for him, after Vidal orders the doctor to heal the rebel in order to torture him more. Vidal asks the doctor why he would do this, when he knows that life would be harder for him for it, and the doctor’s reply is that “only men like you can obey without thinking.” While the doctor speaks against violence on multiple accounts, he is willing to take a life in order to spare it further suffering. He has a better conscience than any other character in the film, represented by his glasses, as he is the only character to wear them. Men like Vidal, morally blind men, cannot understand the decisions of morally sighted men like the doctor. The doctor knows that he will die for his disobedience, but he is willing to die to follow his sense of right and wrong. The doctor and Captain Vidal are also mirrored by their watches. The doctor’s works, and he uses it only to aid him in his healing work, while Vidal’s is broken, and he hides it from everyone else. The doctor’s working watch is symbolic of his good character, and his ability to help others with it, while Vidal’s watch is symbolic of his corrupted ethics.

Mercedes teaches Ofelia justified disobedience in a different way, in a more maternal way. While it’s likely that Mercedes would disagree with Vidal and oppose him regardless, she mainly opposes Vidal because her brother is one of the rebels in the woods. Her familial tie to Vidal’s opponents compels Mercedes to oppose him, and Mercedes’ opposition to Vidal is different from the doctor’s. While the doctor provides services of healing to follow his conscience, Mercedes steals supplies from Vidal’s camp to aid the rebels, and later joins the rebels directly and fights alongside them. Mercedes can even be seen as a leader of the group, giving direction towards the end of the film. It is Vidal’s sexism that allows Mercedes to succeed in this task, not Mercedes’ shrewdness. We know this because Vidal is able to figure out that Mercedes’ works with the rebels, in a scene in which he outsmarts her at every turn and traps her. Mercedes’ escape is due largely to Vidal’s sexism. Even after knowing she is a rebel spy, he insists he does not need help torturing her because she is a woman, dismissing his guards. Since they are alone, Mercedes is able to escape her bonds and permanently disfigure Vidal with a knife. She very symbolically inserts a phallic weapon into an abuser’s mouth, and cuts it open unnaturally wide. This both disrupts Vidal’s male domination and marks him with a permanently gaping maw, symbolic of his greed (Stewart).

Much of the magic in the film is concerned with this theme of moral disobedience that the doctor and Mercedes mirror for Ofelia. The labyrinth itself is a symbol of life and virtue, being full of twisted and confusing decisions, and the entrance of it being crowned with a eyeless statue with an open mouth. All of the magical creatures that Ofelia meets are carnivores, and eat something on screen, pairing with their dark and creepy design to ground them in reality. The faun is Ofelia’s guide through her magical trials, but even he and his fairies are shown to be intentionally deceitful. The fairies lie to her about which door she must open in the Pale Man’s room, and Ofelia is forced to disobey them and follow her own instincts. The faun also lies to her about how she must complete the final trial. He tells her that she must kill her brother, as shedding the blood of the innocent will save her. Ofelia by now has gained moral sight though, and refuses to kill her brother, even though she knows Vidal will kill her if she is caught. The true task was to die to protect an innocent life, not to take one, and Ofelia gains eternal life in the underworld as reward. The magic of the underworld teaches Ofelia not to obey, she has to disobey in order to complete her tasks. It is not obvious to her that she is being taught to disobey, that the real “test of the purity of her soul” is in fact testing her ethics, that she knows when it is right to disobey. The faun even makes her promise to “obey without question,” the same phrase the doctor uses to condemn Captain Vidal. To gain eternal life, Ofelia must be willing to follow her instincts, no matter who she is defying, even to the point of death.

The two characters that Ofelia sees as stand in parental figures, the doctor and Mercedes, also teach her the importance of moral disobedience. The doctor kills one of the rebels out of mercy for him, after Vidal orders the doctor to heal the rebel in order to torture him more. Vidal asks the doctor why he would do this, when he knows that life would be harder for him for it, and the doctor’s reply is that “only men like you can obey without thinking.” While the doctor speaks against violence on multiple accounts, he is willing to take a life in order to spare it further suffering. He has a better conscience than any other character in the film, represented by his glasses, as he is the only character to wear them. Men like Vidal, morally blind men, cannot understand the decisions of morally sighted men like the doctor. The doctor knows that he will die for his disobedience, but he is willing to die to follow his sense of right and wrong. The doctor and Captain Vidal are also mirrored by their watches. The doctor’s works, and he uses it only to aid him in his healing work, while Vidal’s is broken, and he hides it from everyone else. The doctor’s working watch is symbolic of his good character, and his ability to help others with it, while Vidal’s watch is symbolic of his corrupted ethics.

Mercedes teaches Ofelia justified disobedience in a different way, in a more maternal way. While it’s likely that Mercedes would disagree with Vidal and oppose him regardless, she mainly opposes Vidal because her brother is one of the rebels in the woods. Her familial tie to Vidal’s opponents compels Mercedes to oppose him, and Mercedes’ opposition to Vidal is different from the doctor’s. While the doctor provides services of healing to follow his conscience, Mercedes steals supplies from Vidal’s camp to aid the rebels, and later joins the rebels directly and fights alongside them. Mercedes can even be seen as a leader of the group, giving direction towards the end of the film. It is Vidal’s sexism that allows Mercedes to succeed in this task, not Mercedes’ shrewdness. We know this because Vidal is able to figure out that Mercedes’ works with the rebels, in a scene in which he outsmarts her at every turn and traps her. Mercedes’ escape is due largely to Vidal’s sexism. Even after knowing she is a rebel spy, he insists he does not need help torturing her because she is a woman, dismissing his guards. Since they are alone, Mercedes is able to escape her bonds and permanently disfigure Vidal with a knife. She very symbolically inserts a phallic weapon into an abuser’s mouth, and cuts it open unnaturally wide. This both disrupts Vidal’s male domination and marks him with a permanently gaping maw, symbolic of his greed (Stewart).

Much of the magic in the film is concerned with this theme of moral disobedience that the doctor and Mercedes mirror for Ofelia. The labyrinth itself is a symbol of life and virtue, being full of twisted and confusing decisions, and the entrance of it being crowned with a eyeless statue with an open mouth. All of the magical creatures that Ofelia meets are carnivores, and eat something on screen, pairing with their dark and creepy design to ground them in reality. The faun is Ofelia’s guide through her magical trials, but even he and his fairies are shown to be intentionally deceitful. The fairies lie to her about which door she must open in the Pale Man’s room, and Ofelia is forced to disobey them and follow her own instincts. The faun also lies to her about how she must complete the final trial. He tells her that she must kill her brother, as shedding the blood of the innocent will save her. Ofelia by now has gained moral sight though, and refuses to kill her brother, even though she knows Vidal will kill her if she is caught. The true task was to die to protect an innocent life, not to take one, and Ofelia gains eternal life in the underworld as reward. The magic of the underworld teaches Ofelia not to obey, she has to disobey in order to complete her tasks. It is not obvious to her that she is being taught to disobey, that the real “test of the purity of her soul” is in fact testing her ethics, that she knows when it is right to disobey. The faun even makes her promise to “obey without question,” the same phrase the doctor uses to condemn Captain Vidal. To gain eternal life, Ofelia must be willing to follow her instincts, no matter who she is defying, even to the point of death.

Ofelia’s second trial, that of the pale man, is the most striking of the three. Ofelia takes two grapes from his table, and the pale man attempts to eat her as punishment. Parallels between the pale man and Captain Vidal are easy to draw. The pale man appears at the head of the table, and his eyes are in his hands used for grasping, and only uses his eyes when he wants to punish. Captain Vidal appears at the head of a feast earlier in the film, and during it they discuss how they will cut rations of food to the poor outside the wall of the mill. When the rebels come and take some of the food, Vidal hunts down those guilty of helping them. Both Vidal and the pale man have an abundance of food but refuse to share it, and both pursue and punish those who take from them (Perschon). Ofelia disobeys the faun when she takes food from the pale man’s table, and almost dies because of it. It is not morally wrong for her to take food from one with so much, it isn’t a sign of Ofelia’s greed to eat two grapes. It is rather a reminder of the cost of moral disobedience, that one must be willing to risk one’s life to disobey on moral grounds. Ofelia did not know that she was disobeying the faun on moral grounds, but we know that she was from the statement, “I didn’t think anyone would notice two missing grapes.” This is an acknowledgement that Ofelia was aware of the over-abundance that the pale man had, and that one who has so much should not be afraid to lose so little.

Ofelia is rewarded with eternal life at the end of the film. This is in contrast to Vidal, who dies without leaving any remnant of his legacy. Vidal dies because of his moral blindness, his sexism and his obsession with his legacy. He follows Ofelia into the labyrinth and kills her instead of fighting with his men. Ofelia also impairs his ability to function with the medicine her mother was using, symbolically poisoning the father with the medicine of the mother, as he poisoned Carmen with his child. Before Vidal is killed by Mercedes’ brother, again a maternal tie proving to be Vidal’s downfall, Mercedes tells him that his son will not even know his name. He is shot knowing that all the oppression he has caused and all the people he has killed will be for nothing, and that he will leave no legacy. His moral blindness is confirmed even in his death, as after he is shot his right eye rolls back and fills with blood.

Ofelia gains eternal life, and Vidal is damned to be forgotten. Her magical trials were all meant to see if her “soul remained intact,” were all meant to test her moral sight. She must learn to trust her own soul, not the instructions of others, in order to gain it. The faun tells her that the trials “go on” even though her mother is sick, pointing to how the struggle to follow your moral compass does not stop for and cannot be swayed by personal struggles or loss. When Ofelia does enter the underworld, she is wearing a dress bearing the rose of eternity, described in a fairy tale she read to her brother earlier. The rose offered eternal life to any who plucked it, but was surrounded by a field of thorns that caused immense pain, and thus went unplucked. This story is symbolic of how the life that leads to eternal life is difficult, and requires great personal sacrifice, so great that few pursue it. Ofelia has taken this path though, and has earned eternal life in the magical underworld. Her eternal rose, a symbol of growth, stands in opposition to Vidal’s broken watch, emblematic of being trapped in time, lost and pointless. She was willing to die in order to follow her conscience, and gained eternal life through it.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) is a spiritual journey. Del Toro’s magical realism teaches Ofelia and the audience about the necessity of disobedience, and the price and rewards of such disobedience. It condemns those who oppress others, and lifts up those with kind hearts and the will to oppose tyranny. The two worlds work together seamlessly to teach a moral lesson, but also to teach about growing up, and the struggles of adulthood. Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth is a great example of how magical realism allows the themes of both the magical and real worlds to intertwine and come through clearly to the audience. The realistic elements of the magical world and the dramatized, magical aspects of the real world combine to tell a seamless story that would otherwise be impossible.

Perschon, M. (2015, March 24). Embracing the Darkness, Sorrow, and Brutality of Pan's Labyrinth. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://www.tor.com/2011/05/25/the-darkness-of-pans-labyrinth/

Smith, P. J. (summer 2007). Pan's Labyrinth. Film Quarterly, Vol. 60(No. 4). Retrieved May 6, 2020, from https://filmquarterly.org/2007/06/01/pans-labyrinth/

Stewart, S. (2009, August 04). Pan's Labyrinth – A Psychological Analysis. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://www.sdentertainer.com/arts/pans-labyrinth-a-psychological-analysis/

Ofelia is rewarded with eternal life at the end of the film. This is in contrast to Vidal, who dies without leaving any remnant of his legacy. Vidal dies because of his moral blindness, his sexism and his obsession with his legacy. He follows Ofelia into the labyrinth and kills her instead of fighting with his men. Ofelia also impairs his ability to function with the medicine her mother was using, symbolically poisoning the father with the medicine of the mother, as he poisoned Carmen with his child. Before Vidal is killed by Mercedes’ brother, again a maternal tie proving to be Vidal’s downfall, Mercedes tells him that his son will not even know his name. He is shot knowing that all the oppression he has caused and all the people he has killed will be for nothing, and that he will leave no legacy. His moral blindness is confirmed even in his death, as after he is shot his right eye rolls back and fills with blood.

Ofelia gains eternal life, and Vidal is damned to be forgotten. Her magical trials were all meant to see if her “soul remained intact,” were all meant to test her moral sight. She must learn to trust her own soul, not the instructions of others, in order to gain it. The faun tells her that the trials “go on” even though her mother is sick, pointing to how the struggle to follow your moral compass does not stop for and cannot be swayed by personal struggles or loss. When Ofelia does enter the underworld, she is wearing a dress bearing the rose of eternity, described in a fairy tale she read to her brother earlier. The rose offered eternal life to any who plucked it, but was surrounded by a field of thorns that caused immense pain, and thus went unplucked. This story is symbolic of how the life that leads to eternal life is difficult, and requires great personal sacrifice, so great that few pursue it. Ofelia has taken this path though, and has earned eternal life in the magical underworld. Her eternal rose, a symbol of growth, stands in opposition to Vidal’s broken watch, emblematic of being trapped in time, lost and pointless. She was willing to die in order to follow her conscience, and gained eternal life through it.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) is a spiritual journey. Del Toro’s magical realism teaches Ofelia and the audience about the necessity of disobedience, and the price and rewards of such disobedience. It condemns those who oppress others, and lifts up those with kind hearts and the will to oppose tyranny. The two worlds work together seamlessly to teach a moral lesson, but also to teach about growing up, and the struggles of adulthood. Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth is a great example of how magical realism allows the themes of both the magical and real worlds to intertwine and come through clearly to the audience. The realistic elements of the magical world and the dramatized, magical aspects of the real world combine to tell a seamless story that would otherwise be impossible.

Perschon, M. (2015, March 24). Embracing the Darkness, Sorrow, and Brutality of Pan's Labyrinth. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://www.tor.com/2011/05/25/the-darkness-of-pans-labyrinth/

Smith, P. J. (summer 2007). Pan's Labyrinth. Film Quarterly, Vol. 60(No. 4). Retrieved May 6, 2020, from https://filmquarterly.org/2007/06/01/pans-labyrinth/

Stewart, S. (2009, August 04). Pan's Labyrinth – A Psychological Analysis. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://www.sdentertainer.com/arts/pans-labyrinth-a-psychological-analysis/