As I watched Adam McKay’s Don’t Look Up (2021), I felt a certain sense of deja-vu. Where had I seen this before? The final scene of the film, as humanity awaits its inevitable destruction, had me especially feeling reminded of some scene I had seen previously. As I reflected on it, I realized that I was reminded of the 2011 film by Lars Von Trier, Melancholia. Similar to Don’t Look Up, Melancholia focuses on the imminent destruction of the earth due to a collision with a rogue planet. However, Melancholia’s plot is more grounded than Don’t Look Up, offering a much more somber tone than the recent film. Ultimately, I believe that Melancholia’s legacy will far outlast that of Don’t Look Up, because of how the earlier film takes the questions it faces with the utmost sincerity and seriousness. Additionally, the film is not only concerned with death, but also with the despair that can befall the human experience (that is, melancholia). Melancholia is a film which deals with the fundamental elements of the human condition, including the overwhelming nature of free will, choice, and the knowledge of our deaths, and its examination of these elements create an Existential mood which pervades throughout the film.

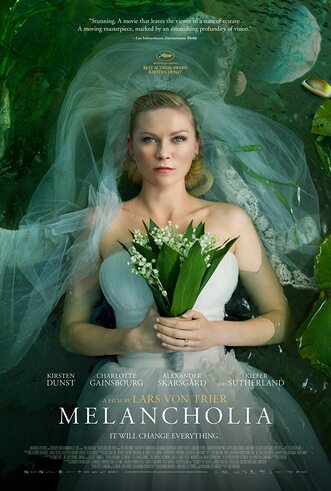

The narrative of Melancholia is split into several sections. In the opening minutes of the film, we are shown an apocalyptic vision of what is to come. Strange images of destruction of nature, the main characters, the collision of Earth with the rogue planet Melancholia. Additionally, we see Justine (Kirsten Dunst), one of the main characters, in her wedding dress, floating peacefully in water. These images offer a premonition of what is to come. We understand that the destruction of Earth is inevitable and fast approaching. Additionally, we know that Justine’s marriage is seemingly not at peace, that it is in some way troubled, as she flees through the woods in her tarnished dress. We then are brought into Part One: “Justine”.

The narrative of Melancholia is split into several sections. In the opening minutes of the film, we are shown an apocalyptic vision of what is to come. Strange images of destruction of nature, the main characters, the collision of Earth with the rogue planet Melancholia. Additionally, we see Justine (Kirsten Dunst), one of the main characters, in her wedding dress, floating peacefully in water. These images offer a premonition of what is to come. We understand that the destruction of Earth is inevitable and fast approaching. Additionally, we know that Justine’s marriage is seemingly not at peace, that it is in some way troubled, as she flees through the woods in her tarnished dress. We then are brought into Part One: “Justine”.

Part One follows the story of Justine on her wedding day. Justine is to be married to Michael (Alexander Skarsgard), the son of a wealthy family. The couple are to be married at a castle belonging to Justine’s sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and brother-in-law John (Kiefer Sutherland). While things initially seem to be going well for the couple, the events of the evening quickly dissolve into chaos. Justine suffers with extreme depression, and finds herself no longer caring about her marriage. This apathy seems to come from two simultaneous conditions. The first is that Justine suffers from an acute case of medical depression. However, she also attributes much of her suffering to what is expected of her. On her wedding night, Justine’s boss gives her a promotion that she does not feel that she wants, and then expects her to create a slogan, that is, to do her job, that very night. Simultaneously, Justine feels a great deal of pressure to be married, made obvious by the harsh directions given to her by her parents. Many aspects of Justine’s life have been decided on her behalf. She now finds herself stuck in a miserable situation, and this misery is compounded by her preexisting mental health issues.

The first chapter of Melancholia highlights two significant Existentialist themes. The first is the inescapable nature of choice. Soren Kierkegaard, the father of Existentialism, frequently discussed the nature of freedom, and how human freedom could become overwhelming when faced with a choice. Additionally, Kierkegaard believed that we are always, at all times, faced with choice, and as such, if we were fully aware of this constant horizon of possibility, we could become paralyzed by options. In his essay Either/Or, Kierkegaard describes the tension that Justine experiences as she decides whether or not to carry through with her wedding. “I see it all perfectly,” Kierkegaard writes, “there are two possible situations — one can either do this or that. My honest opinion and my friendly advice is this: do it or do not do it — you will regret both… Marry or do not marry, you will regret it either way.” What Kierkegaard recognizes in Either/Or is that the constant human condition (that is, the condition of human existence, hence ‘existentialism’) is always inundated with choice. What’s worse, we cannot know the outcome of our choices until after we have made them. Even worse still is the fact that we never truly know what might have happened had we chosen otherwise, thus leading us to “regret it either way”. Kierkegaard understood that refusing to make a choice is itself a choice - to remain where one is. Because of this non-choice being itself a choice, we are truly trapped in our freedom. As Jean-Paul Sartre put it, humanity is “condemned to be free.”

On the one hand, Justine finds herself to be overwhelmed by the choice of whether or not to marry. Her family expects her to marry, yet her heart is not in it. At the same time, her employers give her positions and task her with duties which she does not care about, and at times which are entirely inappropriate and inconvenient. At her wedding, Justine finds herself thrust into roles which she is expected to fill, yet these roles are those which she cares nothing about. Justine is then, as Kierkegaard recognizes, faced with the choice between fulfilling what is expected of her on the one hand, and defiance and rebellion, an act of her own will, on the other. This is a commonly recognized existential mode of being. Kierkegaard described this tension between the expectations placed on one and the infinite possibility of human freedom as a tension between the finite (one’s current conditions) and the infinite (the horizon of possibility). Jean-Paul Sartre similarly recognized this tension, describing the conditions of our thrownness (where we are born, our neurochemistry, our pre-existing beliefs) as our “facticity” and the human experience of infinite freedom as our “transcendence” (the ability to transcend our facticity to generate a new reality). Both Sartre and Kierkegaard would see Justine’s situation as an existential one, and one which every human must face. There is always a tension between where we are and where we could be. If we become too limited by the roles thrust upon us, losing sight of possibility, we become lost in our facticity. On the other hand, we might become so paralyzed by the infinite horizon of choice that we simply make no choice at all (which, as Kierkegaard says, is itself a choice) and become lost in our transcendence.

When we become overwhelmed with these two poles of our reality, unable to make a choice to commit ourselves to either our facticity or to our transcendence, we fall into a sense of despair. Despair is an important existential theme, playing a central role in the philosophical movement. While despair means slightly different things to different philosophers, it can generally be described as a sort of death-before-death that comes from a breakdown of one’s self-identity. This breakdown comes from a recognition of the limits of one's self without the strength to transcend these limitations. In Justine’s case, her despair (in the existential sense) comes from a simultaneous recognition of the limitations imposed on her by her family, friends and employers (facticity) and a recognition of her lack of will to transcend these limitations. Because of this, Justine enters a state of melancholic despair in which she can barely function.

It is significant that this inward death, the death-before-death, occurs before the greater outward death of the rogue planet. Justine seems to have a sort of premonitory power, as she receives visions of the approaching apocalypse. This vision, as seen through the symbolic lens of Existentialism, is simultaneously a contributing factor to her despair (that is, the knowledge of her inevitable death leads to despair) and is simultaneously grounded by that despair. Put in non-symbolic terms, Melancholia seems to suggest that our state of despair is grounded in the knowledge of our death, but that the premonitory knowledge of our impending death is itself grounded in despair. There is a symbiotic relationship between the premonitory knowledge of death and the experience of despair - both ground and produce the other. Paradoxically, it is only after this premonition and despair that Justine is able to transcend the fact of her death and come to accept her death boldly.

The first chapter of Melancholia highlights two significant Existentialist themes. The first is the inescapable nature of choice. Soren Kierkegaard, the father of Existentialism, frequently discussed the nature of freedom, and how human freedom could become overwhelming when faced with a choice. Additionally, Kierkegaard believed that we are always, at all times, faced with choice, and as such, if we were fully aware of this constant horizon of possibility, we could become paralyzed by options. In his essay Either/Or, Kierkegaard describes the tension that Justine experiences as she decides whether or not to carry through with her wedding. “I see it all perfectly,” Kierkegaard writes, “there are two possible situations — one can either do this or that. My honest opinion and my friendly advice is this: do it or do not do it — you will regret both… Marry or do not marry, you will regret it either way.” What Kierkegaard recognizes in Either/Or is that the constant human condition (that is, the condition of human existence, hence ‘existentialism’) is always inundated with choice. What’s worse, we cannot know the outcome of our choices until after we have made them. Even worse still is the fact that we never truly know what might have happened had we chosen otherwise, thus leading us to “regret it either way”. Kierkegaard understood that refusing to make a choice is itself a choice - to remain where one is. Because of this non-choice being itself a choice, we are truly trapped in our freedom. As Jean-Paul Sartre put it, humanity is “condemned to be free.”

On the one hand, Justine finds herself to be overwhelmed by the choice of whether or not to marry. Her family expects her to marry, yet her heart is not in it. At the same time, her employers give her positions and task her with duties which she does not care about, and at times which are entirely inappropriate and inconvenient. At her wedding, Justine finds herself thrust into roles which she is expected to fill, yet these roles are those which she cares nothing about. Justine is then, as Kierkegaard recognizes, faced with the choice between fulfilling what is expected of her on the one hand, and defiance and rebellion, an act of her own will, on the other. This is a commonly recognized existential mode of being. Kierkegaard described this tension between the expectations placed on one and the infinite possibility of human freedom as a tension between the finite (one’s current conditions) and the infinite (the horizon of possibility). Jean-Paul Sartre similarly recognized this tension, describing the conditions of our thrownness (where we are born, our neurochemistry, our pre-existing beliefs) as our “facticity” and the human experience of infinite freedom as our “transcendence” (the ability to transcend our facticity to generate a new reality). Both Sartre and Kierkegaard would see Justine’s situation as an existential one, and one which every human must face. There is always a tension between where we are and where we could be. If we become too limited by the roles thrust upon us, losing sight of possibility, we become lost in our facticity. On the other hand, we might become so paralyzed by the infinite horizon of choice that we simply make no choice at all (which, as Kierkegaard says, is itself a choice) and become lost in our transcendence.

When we become overwhelmed with these two poles of our reality, unable to make a choice to commit ourselves to either our facticity or to our transcendence, we fall into a sense of despair. Despair is an important existential theme, playing a central role in the philosophical movement. While despair means slightly different things to different philosophers, it can generally be described as a sort of death-before-death that comes from a breakdown of one’s self-identity. This breakdown comes from a recognition of the limits of one's self without the strength to transcend these limitations. In Justine’s case, her despair (in the existential sense) comes from a simultaneous recognition of the limitations imposed on her by her family, friends and employers (facticity) and a recognition of her lack of will to transcend these limitations. Because of this, Justine enters a state of melancholic despair in which she can barely function.

It is significant that this inward death, the death-before-death, occurs before the greater outward death of the rogue planet. Justine seems to have a sort of premonitory power, as she receives visions of the approaching apocalypse. This vision, as seen through the symbolic lens of Existentialism, is simultaneously a contributing factor to her despair (that is, the knowledge of her inevitable death leads to despair) and is simultaneously grounded by that despair. Put in non-symbolic terms, Melancholia seems to suggest that our state of despair is grounded in the knowledge of our death, but that the premonitory knowledge of our impending death is itself grounded in despair. There is a symbiotic relationship between the premonitory knowledge of death and the experience of despair - both ground and produce the other. Paradoxically, it is only after this premonition and despair that Justine is able to transcend the fact of her death and come to accept her death boldly.

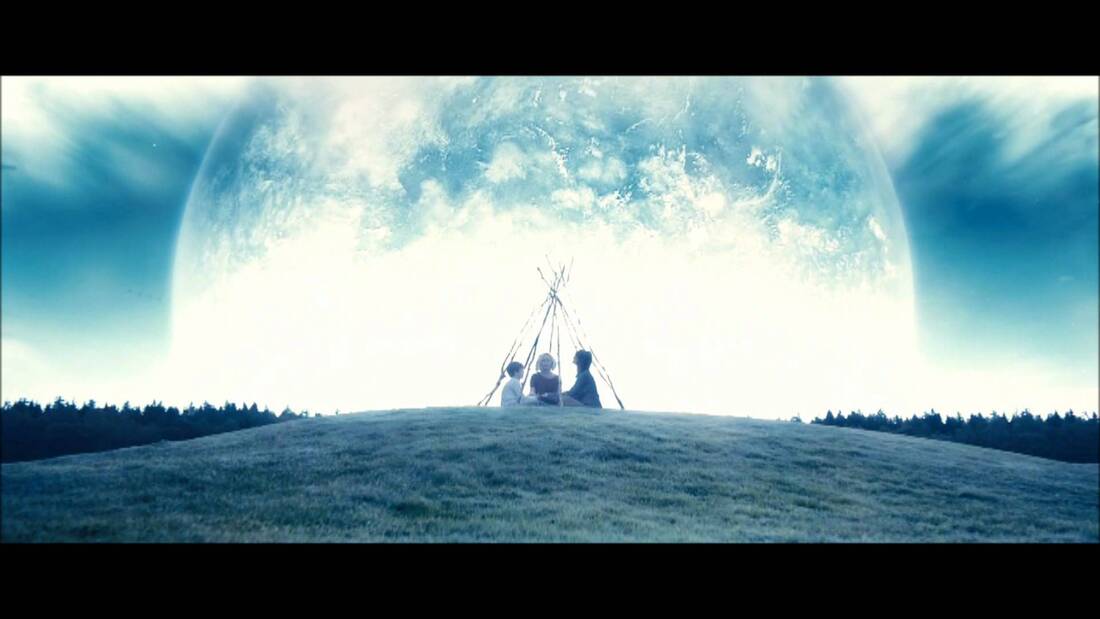

Part of Justine's premonitory vision

The second half of Melancholia focuses on Justine’s sister Claire, and her discovery of the imminently approaching rogue planet Melancholia. Throughout this chapter, we are presented with a variety of stages of grief. John begins by denying the threat at all, insisting that scientists are certain there will be no collision. The couple bickers as tensions rise, bringing us to anger. Claire then begins to move into the state of despair, leading into the moment of depression. John and Claire both engage in bargaining, as John attempts to prepare for the event by purchasing gas and food. Claire, meanwhile, attempts to run from the catastrophe, taking her son on a golf cart with her, with no destination available to her for escape. In a second step of bargaining, John commits suicide. I say here that John’s suicide is not a moment of acceptance, but instead bargaining, because John is still attempting to control the moment of his death in order to escape the ultimate death which is the extinction of humanity. The act of suicide is well explored by existentialist thinkers, especially by Albert Camus, who saw suicide as the fundamental philosophical question. It is only Justine who is able to fully accept her death, facing it bravely and choosing to help her nephew to face his death as well, through the use of the “magic fort”. Here, the magic fort can be seen as the absurd attempt at meaning-making in the face of death. That is, we are able to make our constructions which help us to face our deaths, while simultaneously recognizing, as Justine does, that these are merely constructions.

The knowledge of the approach of one’s death is at the heart of Existentialism. More significantly, the focus of existential thinkers is not just on the claim “All people die” but on the deep, personal knowledge that “I will die” which is simultaneously inescapably obvious and unthinkable. This knowledge of my death specifically, as opposed to any other person’s death, is often seen as the foundation of the human experience. Human experience, as understood through this impending death, is closely tied with anxiety. Philosopher and theologian Paul Tillich, in his work The Courage to Be, described the most fundamental anxiety as an ontological anxiety. Ontology is concerned with existence or being, that is, about what exists and what doesn’t. Therefore, ontological anxiety is about a Being’s necessary knowledge and fear of non-being. Tillich suggests that humanity needs a suitable courage in order to be able to face the ontological anxiety of non-being. He called such a courage a “courage to be”, or an ontological self affirmation. As Tillich puts it, the courage to be is “the ethical act in which man affirms his own being in spite of those elements of his existence which conflict with his essential self-affirmation.”

Likewise, Heidegger, an extremely influential philosopher of existentialism and phenomenology (the study of what it is like to be human) recognized an anxiety towards death as fundamental to the human experience. Heidegger associated Dasein (the human way of being) with what he called a “Being-toward-death”. Being-toward-death refers to a sense of engaging in the world with a constant foresight or premonition of one’s death. And this foresight gives us a more genuine understanding of the world and how to be and behave within the world. At the same time, the Being-toward-death is a state of being which is directed towards the unimaginable. As Dasein is being, it is impossible for being to imagine the possibility of non-being. Non-being is the possibility for Dasein which is also impossible, as it cannot be conceived of, cannot be experienced, and cannot be compared with any other experience. This is where Heidegger differentiates between anxiety and fear. Fear has an object which it is directed towards, such as a fear of spiders, or of heights. However, anxiety has no object. Anxiety is towards something vague, not any particular thing, indeed, it is towards nothing. The unknown nature of death and our Being-toward-death can cause an anxiety from the unknown.

The knowledge of the approach of one’s death is at the heart of Existentialism. More significantly, the focus of existential thinkers is not just on the claim “All people die” but on the deep, personal knowledge that “I will die” which is simultaneously inescapably obvious and unthinkable. This knowledge of my death specifically, as opposed to any other person’s death, is often seen as the foundation of the human experience. Human experience, as understood through this impending death, is closely tied with anxiety. Philosopher and theologian Paul Tillich, in his work The Courage to Be, described the most fundamental anxiety as an ontological anxiety. Ontology is concerned with existence or being, that is, about what exists and what doesn’t. Therefore, ontological anxiety is about a Being’s necessary knowledge and fear of non-being. Tillich suggests that humanity needs a suitable courage in order to be able to face the ontological anxiety of non-being. He called such a courage a “courage to be”, or an ontological self affirmation. As Tillich puts it, the courage to be is “the ethical act in which man affirms his own being in spite of those elements of his existence which conflict with his essential self-affirmation.”

Likewise, Heidegger, an extremely influential philosopher of existentialism and phenomenology (the study of what it is like to be human) recognized an anxiety towards death as fundamental to the human experience. Heidegger associated Dasein (the human way of being) with what he called a “Being-toward-death”. Being-toward-death refers to a sense of engaging in the world with a constant foresight or premonition of one’s death. And this foresight gives us a more genuine understanding of the world and how to be and behave within the world. At the same time, the Being-toward-death is a state of being which is directed towards the unimaginable. As Dasein is being, it is impossible for being to imagine the possibility of non-being. Non-being is the possibility for Dasein which is also impossible, as it cannot be conceived of, cannot be experienced, and cannot be compared with any other experience. This is where Heidegger differentiates between anxiety and fear. Fear has an object which it is directed towards, such as a fear of spiders, or of heights. However, anxiety has no object. Anxiety is towards something vague, not any particular thing, indeed, it is towards nothing. The unknown nature of death and our Being-toward-death can cause an anxiety from the unknown.

The planet Melancholia, about to impact the Earth

The film sharply draws our attention to this anxiety of non-being, as demonstrated by the rogue planet on its course for Earth. As both Tillich and Heidegger suggest, an awareness of our death is fundamental to the human experience. Heidegger suggests that our death is such a fundamental part of our life that “as soon as man comes to life, he is at once old enough to die”. The knowledge of our death is the very ground by which we find our being in the world. Melancholia represents this with the montage at the beginning of the film, which is constantly in the back of our minds throughout the film. It provides the grounds of our anxiety.

Melancholia’s premonitory vision of the coming non-being provides the grounds for the despair of indecision in Chapter 1. It begins by demonstrating this indecision in Justine. It then moves into the more fundamental question of the threat of non-being. In a sense, the first half of the film may be seen as an examination of the anxiety of being, that is, the anxiety of being in the world. This is juxtaposed with the ontological question of non-being, which is more fundamental and more significant than the anxiety of being depicted in the first chapter. The weight of the ontological threat of non-being is not just discussed abstractly - it is felt. Indeed, it is only after engaging with the feeling of anxiety that we can begin to discuss that anxiety; without first recognizing this feeling, how do we even know what we are speaking about? The anxiety of choice which is at the heart of the first chapter feels insignificant compared with the anxiety of the second chapter, and we feel this significance deep in our bones. Melancholia’s greatest achievement is in drawing out and making explicit the anxieties which are most often repressed and merely implicit in our experience.

Melancholia’s premonitory vision of the coming non-being provides the grounds for the despair of indecision in Chapter 1. It begins by demonstrating this indecision in Justine. It then moves into the more fundamental question of the threat of non-being. In a sense, the first half of the film may be seen as an examination of the anxiety of being, that is, the anxiety of being in the world. This is juxtaposed with the ontological question of non-being, which is more fundamental and more significant than the anxiety of being depicted in the first chapter. The weight of the ontological threat of non-being is not just discussed abstractly - it is felt. Indeed, it is only after engaging with the feeling of anxiety that we can begin to discuss that anxiety; without first recognizing this feeling, how do we even know what we are speaking about? The anxiety of choice which is at the heart of the first chapter feels insignificant compared with the anxiety of the second chapter, and we feel this significance deep in our bones. Melancholia’s greatest achievement is in drawing out and making explicit the anxieties which are most often repressed and merely implicit in our experience.