A Woman's Perspective:

Gender, and Identity in Ryna and Child’s Pose

by Jessica Cizauskas

This study evaluates the films Ryna (Zenide, 2005) and Child’s Pose (Netzer, 2013) in light of how women in Romanian films are currently viewed, their gender roles, their expectations as mothers and how female directors are treated. This analytic is helpful in revealing how complicated the inequality is in current and previous social arrangements. Therefore, social-realist films like Ryna and Child's Pose can highlight the reality of gender roles, patriarchy, female directors, and identity in Romania and how far they are from equality.

The Romanian New Wave brought world attention to the country’s cinema starting in the 2000s, when a generation of directors started to create productions that were different from the Romanian films produced during the communist regime (Nasta 123). Often the films that are part of this wave are realized with small budgets and feature long and wide shots, diegetic sound, minor scene editing, real-time sequences, hand held cameras, a minimalist style, and a simple/straightforward storyline that rarely follows the dictations of mainstream cinema. These films are committed to rendering on-screen realism because they represent how Romania evolved after 1989. These directors could also be seen as rebelling against the “the artistic compromises of films released during communism. The lies promoted through cinema by communist propaganda triggered the drastic commitment of this new generation to telling the truth, and, hence, to getting as close as possible to reality in storytelling and filming techniques” (Adina and Mădroane 101). Often the themes in the films address subjects like absurdism, gender, identity, patriarchy, motherhood, cinematic reenactments of past events, transmediality, and multimediality (the osmotic interplay between cinema, radio, television, and digital media). These films create a great opportunity to observe how gender roles, power relations, and the relationship between the state and the individual are revealed through cinematography. However, the film world in Romania is still quite male dominated and there aren't many female directors that are well known. The YouTube channel BEAST International Film Festival offers a view of women that are part of the Romanian film industry; in the video presented, three women discuss how gender dynamics are treated in the European film industry, focusing their gaze specifically on Romania.

The Romanian New Wave brought world attention to the country’s cinema starting in the 2000s, when a generation of directors started to create productions that were different from the Romanian films produced during the communist regime (Nasta 123). Often the films that are part of this wave are realized with small budgets and feature long and wide shots, diegetic sound, minor scene editing, real-time sequences, hand held cameras, a minimalist style, and a simple/straightforward storyline that rarely follows the dictations of mainstream cinema. These films are committed to rendering on-screen realism because they represent how Romania evolved after 1989. These directors could also be seen as rebelling against the “the artistic compromises of films released during communism. The lies promoted through cinema by communist propaganda triggered the drastic commitment of this new generation to telling the truth, and, hence, to getting as close as possible to reality in storytelling and filming techniques” (Adina and Mădroane 101). Often the themes in the films address subjects like absurdism, gender, identity, patriarchy, motherhood, cinematic reenactments of past events, transmediality, and multimediality (the osmotic interplay between cinema, radio, television, and digital media). These films create a great opportunity to observe how gender roles, power relations, and the relationship between the state and the individual are revealed through cinematography. However, the film world in Romania is still quite male dominated and there aren't many female directors that are well known. The YouTube channel BEAST International Film Festival offers a view of women that are part of the Romanian film industry; in the video presented, three women discuss how gender dynamics are treated in the European film industry, focusing their gaze specifically on Romania.

Based on this discussion with those involved in the Romanian film industry, the reason there are more male directors and producers rather than female ones in the film industry has to do with how women are treated in Romania and their expectations in society. Also, knowing that the majority of directors in Romania are males begs the question: how exactly are women represented in this new wave of cinema?

Although Romanian law recognizes the equality of chances between men and women, families are traditionally patriarchal, and tradition still places the woman in a lower position than the man. Women are expected to be stay-at-home mothers and run the household, while the men are the main providers. Essentially: “a sacrificial role of women across regimes, and continues the idea that motherhood was and still is considered to be the most important female “duty”, as a result of societal values and asymmetrical power relations. Which was a narrative used during communism in Romania, the only difference being that currently the subject of total devotion is only the child, not the nation as well.” (Letitia 109). Romanian women generally have a lot of authority in their households as mothers, and have a deep pride in their cooking. They are also expected to maintain a feminine look that is well groomed because Romanians generally possess strong conceptions regarding standards, as well as what is feminine and what is masculine. Women and girls are still pressured to be mothers, especially in rural areas where it often ends up being their life-goal; if they don’t fulfill this standard by marrying within a certain age, they could be considered to be immoral human beings or “less of a woman”. The women who refuse to follow these traditions and decide to join the workforce tend to dominate low-status/low-paying jobs, are sexualized in their communities and at work, and don't occupy as many leadership positions, especially in politics (Pier). These traditionally patriarchal ideals contribute to the lack of female directors and limiting gender to what society is expecting of them, ultimately impacting the potential of the development of the country.

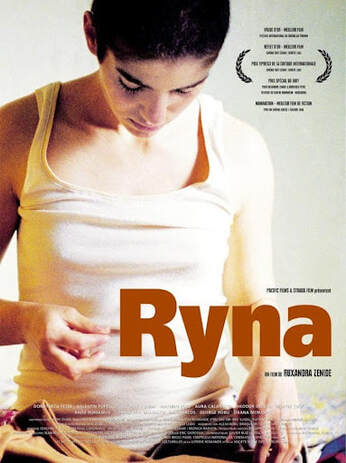

The women who are labeled as aggressive, strong-willed, independent, lacking empathy, ambitious, modern, and are willing to fight their way up the social hierarchy are considered ‘manly women’. These are the women who are considered to be causing the emasculation of the men around them, and sometimes those men resort to violence as a desperate act to reaffirm their masculinity, which is a prominent theme in the film Ryna, by female director Ruxandra Zenide. This coming of age film follows the story of Ryna (Dorotheea Petre), a 16-year-old girl who lives in a rural town, and her search to find her identity and femininity within the canons allowed by Romanian society. However, as her father (Valentin Popescu) wanted a son, he forces her to look and act like a boy; although Ryna is not subjected to the expectations Romanian society imposes on its women and is not allowed to express her true gender identity, this doesn’t stop men of the town from sexualizing her. Because of her upbringing, Ryna lives in a limbo in which she is not permitted to act like a woman, and at the same time has to fulfill her father’s wish of becoming a mechanic, pushing aside her goal of becoming a photographer.

Although Romanian law recognizes the equality of chances between men and women, families are traditionally patriarchal, and tradition still places the woman in a lower position than the man. Women are expected to be stay-at-home mothers and run the household, while the men are the main providers. Essentially: “a sacrificial role of women across regimes, and continues the idea that motherhood was and still is considered to be the most important female “duty”, as a result of societal values and asymmetrical power relations. Which was a narrative used during communism in Romania, the only difference being that currently the subject of total devotion is only the child, not the nation as well.” (Letitia 109). Romanian women generally have a lot of authority in their households as mothers, and have a deep pride in their cooking. They are also expected to maintain a feminine look that is well groomed because Romanians generally possess strong conceptions regarding standards, as well as what is feminine and what is masculine. Women and girls are still pressured to be mothers, especially in rural areas where it often ends up being their life-goal; if they don’t fulfill this standard by marrying within a certain age, they could be considered to be immoral human beings or “less of a woman”. The women who refuse to follow these traditions and decide to join the workforce tend to dominate low-status/low-paying jobs, are sexualized in their communities and at work, and don't occupy as many leadership positions, especially in politics (Pier). These traditionally patriarchal ideals contribute to the lack of female directors and limiting gender to what society is expecting of them, ultimately impacting the potential of the development of the country.

The women who are labeled as aggressive, strong-willed, independent, lacking empathy, ambitious, modern, and are willing to fight their way up the social hierarchy are considered ‘manly women’. These are the women who are considered to be causing the emasculation of the men around them, and sometimes those men resort to violence as a desperate act to reaffirm their masculinity, which is a prominent theme in the film Ryna, by female director Ruxandra Zenide. This coming of age film follows the story of Ryna (Dorotheea Petre), a 16-year-old girl who lives in a rural town, and her search to find her identity and femininity within the canons allowed by Romanian society. However, as her father (Valentin Popescu) wanted a son, he forces her to look and act like a boy; although Ryna is not subjected to the expectations Romanian society imposes on its women and is not allowed to express her true gender identity, this doesn’t stop men of the town from sexualizing her. Because of her upbringing, Ryna lives in a limbo in which she is not permitted to act like a woman, and at the same time has to fulfill her father’s wish of becoming a mechanic, pushing aside her goal of becoming a photographer.

This aspiration of becoming a photographer means that Ryna has no intentions of sacrificing her desires to fulfill her father’s dream and live the rest of her life as a boy, but at the same time is not willing to follow the societal expectations for women and becoming a mother.

She begins to use her femininity to rebel against her father, growing her hair to be longer in order to attend a local fair, considered to be a rite of passage for young ladies. However, every attempt to embrace her femininity is undermined: she attempts to pierce her ears, but ends up in the hospital because she is hemophiliac; when she attempts to grow her hair to attend the fair she receives the full support of her mother (Aura Calarasu), but the woman is too physically and emotionally weak to face her husband. Thus, causing Ryna’s father to shave her head himself and forbid her from going to the local fair. Essentially, she is punished each time she tries to assert herself as a woman. When her father shaves her head, her overalls are down and a group of young men spy on her because she is half naked. Several men from the town begin to develop sexual interest in Ryna, and her family ultimately fails to protect her. These men include the mayor (George Custura) and a French foreigner (Matthieu Rozé) who, to quote director Ruxandra Zenide: “Is almost a dream, an idealization of something different: economically, politically, socially. As an emigrant you might gain freedom, but you always lose something: culture, roots, identity,” (Pfeifer and Ribeiro).

Both Ryna and her mother perform acts of rebellion: her mother abandons her family to moves in Bucharest with her sister, while Ryna goes to the fair wearing a pink dress, openly flirts with the French foreigner, goes for a walk with him, and kisses him; surprisingly, he respects her decision to go home after they kiss. Immediately after, Ryna goes back to the town to find her drunk father. She finds him with the mayor, who proceeds to lead her father in a field and waits for him to pass out before going back to Ryna and raping her. Because the family’s gas station needs a permit from the mayor to keep running, she doesn’t turn her rapist over to the police. Frustrated by her situation, Ryna, in one last act of rebellion, leaves the town to meet her mother in the capital city. The last scene is a metaphor for how Ryna, by following her mother’s steps, is also leaving behind the roles set by the society for women. They both were victims of an environment dominated by men, and sadly the Romanian countryside is still like this as of today.

Ryna deals with gender and identity in Romanian society, but it also “asks broader political questions. For the filmmaker, Ryna became an allegory of Romania itself. Like Ryna, Romania is a country torn between archaic political obscurantism, and the strong will to adapt to transparent democratizing standards” (Ribeiro). Ryna’s identity is something that the people around her shape, and much of the plot is spent with her trying to figure out who she wants to be while still struggling to leave behind traditions and her father’s desires. She tries her hardest to go against societal and gender norms and in doing so she is punished. Ryna can only exist within the canons of what other characters put into her: they are all responsible for her rape and in her final decision to leave the paternalistic society, or the ‘men’s world,’ of her rural town behind.

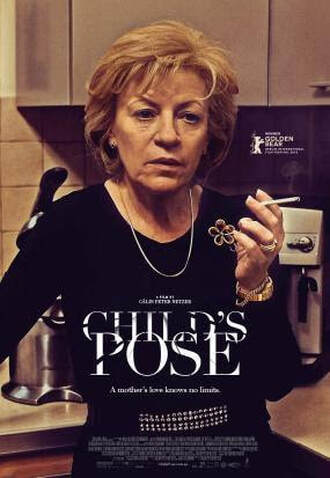

As mentioned above, motherhood is a concept that drives women in Romanian society. In the film Child’s Pose by male director Călin Peter Netzer, the main character is Cornelia (Luminița Gheorghiu), a well-connected and wealthy architect who is also a traditionally overprotective and suffocating mother who pampers Barbu, her son, to no end. One day she learns that Barbu (Bogdan Dumitrache), with whom she already has a very rocky relationship, was involved in a car accident and killed a young boy. The plot revolves around the concept of an overbearing mother who is ready to do anything to protect her son - up to and including: bribing witnesses, falsifying police reports, and pressuring the family of the dead boy to not press charges. Alongside her motherly preoccupation comes the theme of male entitlement, as she seems to be doing everything to protect her son from facing the consequences of his own actions and decides to believe him to be innocent even if he is clearly in the wrong.

Just like Ryna, Cornelia can be considered a ‘manly woman’: she is an aggressive, ambitious, authoritarian, and ferocious, someone who does whatever is necessary to protect her beloved son. Also, both male characters in the film are portrayed as weak, especially if compared to the strong personality of Cornelia. Her husband (Florin Zamfirescu) lives in his wife’s shadows, which is strange in a patriarchal society like the Romanian one. Even though he is the breadwinner of the household, he is portrayed in a way that makes him seem like he resents his wife, as he can’t control her to the point of having lost all of his power to her. Barbu experiences the same situation: he can't find his own path, is dependent on his parents (mostly his mother), and lacks confidence. “This is an inversion of traditional Romanian gender stereotypes, where the female protagonist represents the authority. Cornelia’s lack of empathy situates her in antagonism with the image of the traditional woman (weak and subordinated), basically contradicting what social norms usually dictate” (Letitia 121).

One of the hardest scenes to watch in the movie is early on, when Cornelia rushes to the police station where her son is being questioned, and shows herself to be fully ready to protest against the accusations against Barbu that she thinks are unjust.

She begins to use her femininity to rebel against her father, growing her hair to be longer in order to attend a local fair, considered to be a rite of passage for young ladies. However, every attempt to embrace her femininity is undermined: she attempts to pierce her ears, but ends up in the hospital because she is hemophiliac; when she attempts to grow her hair to attend the fair she receives the full support of her mother (Aura Calarasu), but the woman is too physically and emotionally weak to face her husband. Thus, causing Ryna’s father to shave her head himself and forbid her from going to the local fair. Essentially, she is punished each time she tries to assert herself as a woman. When her father shaves her head, her overalls are down and a group of young men spy on her because she is half naked. Several men from the town begin to develop sexual interest in Ryna, and her family ultimately fails to protect her. These men include the mayor (George Custura) and a French foreigner (Matthieu Rozé) who, to quote director Ruxandra Zenide: “Is almost a dream, an idealization of something different: economically, politically, socially. As an emigrant you might gain freedom, but you always lose something: culture, roots, identity,” (Pfeifer and Ribeiro).

Both Ryna and her mother perform acts of rebellion: her mother abandons her family to moves in Bucharest with her sister, while Ryna goes to the fair wearing a pink dress, openly flirts with the French foreigner, goes for a walk with him, and kisses him; surprisingly, he respects her decision to go home after they kiss. Immediately after, Ryna goes back to the town to find her drunk father. She finds him with the mayor, who proceeds to lead her father in a field and waits for him to pass out before going back to Ryna and raping her. Because the family’s gas station needs a permit from the mayor to keep running, she doesn’t turn her rapist over to the police. Frustrated by her situation, Ryna, in one last act of rebellion, leaves the town to meet her mother in the capital city. The last scene is a metaphor for how Ryna, by following her mother’s steps, is also leaving behind the roles set by the society for women. They both were victims of an environment dominated by men, and sadly the Romanian countryside is still like this as of today.

Ryna deals with gender and identity in Romanian society, but it also “asks broader political questions. For the filmmaker, Ryna became an allegory of Romania itself. Like Ryna, Romania is a country torn between archaic political obscurantism, and the strong will to adapt to transparent democratizing standards” (Ribeiro). Ryna’s identity is something that the people around her shape, and much of the plot is spent with her trying to figure out who she wants to be while still struggling to leave behind traditions and her father’s desires. She tries her hardest to go against societal and gender norms and in doing so she is punished. Ryna can only exist within the canons of what other characters put into her: they are all responsible for her rape and in her final decision to leave the paternalistic society, or the ‘men’s world,’ of her rural town behind.

As mentioned above, motherhood is a concept that drives women in Romanian society. In the film Child’s Pose by male director Călin Peter Netzer, the main character is Cornelia (Luminița Gheorghiu), a well-connected and wealthy architect who is also a traditionally overprotective and suffocating mother who pampers Barbu, her son, to no end. One day she learns that Barbu (Bogdan Dumitrache), with whom she already has a very rocky relationship, was involved in a car accident and killed a young boy. The plot revolves around the concept of an overbearing mother who is ready to do anything to protect her son - up to and including: bribing witnesses, falsifying police reports, and pressuring the family of the dead boy to not press charges. Alongside her motherly preoccupation comes the theme of male entitlement, as she seems to be doing everything to protect her son from facing the consequences of his own actions and decides to believe him to be innocent even if he is clearly in the wrong.

Just like Ryna, Cornelia can be considered a ‘manly woman’: she is an aggressive, ambitious, authoritarian, and ferocious, someone who does whatever is necessary to protect her beloved son. Also, both male characters in the film are portrayed as weak, especially if compared to the strong personality of Cornelia. Her husband (Florin Zamfirescu) lives in his wife’s shadows, which is strange in a patriarchal society like the Romanian one. Even though he is the breadwinner of the household, he is portrayed in a way that makes him seem like he resents his wife, as he can’t control her to the point of having lost all of his power to her. Barbu experiences the same situation: he can't find his own path, is dependent on his parents (mostly his mother), and lacks confidence. “This is an inversion of traditional Romanian gender stereotypes, where the female protagonist represents the authority. Cornelia’s lack of empathy situates her in antagonism with the image of the traditional woman (weak and subordinated), basically contradicting what social norms usually dictate” (Letitia 121).

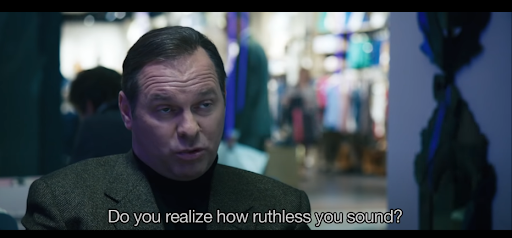

One of the hardest scenes to watch in the movie is early on, when Cornelia rushes to the police station where her son is being questioned, and shows herself to be fully ready to protest against the accusations against Barbu that she thinks are unjust.

When she gets there she has to sit in the waiting room with the family of the dead child. At this moment she knows that she has to appeal to the victims' family by paying for the funeral and paying a condolence visit, even though her main objective is to pull as many strings as possible to keep her son out of jail. “Her canny navigation of a system that still runs on favors and bribes represents an almost atavistic return to Soviet-era form in a society that’s still in the painful throes of defining workable forms of civility and accountability” (Hornaday). Cornelia could be seen as being a metaphor for the lingering effects left by Mother Russia: an overbearing and oppressive mother. The worst part of the matter is that her entitled son doesn’t accept her help and keeps insisting that he’s going to take care of the situation himself while simultaneously doing nothing both because he’s still in shock over having killed someone and because he’s too dense to try to dig his way out.

Cornelia even sits down with the witness to bribe him to lie about the accident in favor of her son, which is a glimpse into the social order in which everything is a potential commodity, including justice and truth.

The defining moment of the film is the ending, in which Cornelia pays her condolences to the family of the boy her son killed, while Barbu stays in the car, too much of a coward to take responsibility for his actions and apologize to the family directly.

Once again, Cornelia does everything she can to protect her son, and to quote the movie, she says: “I came here on behalf of my boy. He’s outside and couldn't come in the poor thing. He’s suffering terribly. He didn't mean it. He wanted to tell you and me too. What can I tell you. I’m so sorry… When they told me: ‘Barbu was in an accident,’ I thought the world had ended. And that’s nothing compared to what you’re going through. It’s nothing... No one was guilty, yet here's the terrible misfortune. Your child wasn't meant to die, and my child didn’t mean to do harm” (Netzer).

The film Child’s Pose showcases the role of a mother who protects her son and the different gender roles in an unequal social structure. Although Cornelia did conform to the societal norm of being a mother, she did take her role in the household to a new level by being the authority figure over both of her male family members. Women are still represented in the film as being sacrificial; however there is this shift from mothers being heroic to being perceived as monstrous and maddening, and Cornelia is a prominent example of this. Throughout the process of trying to save her son from going to jail, Cornelia is rejected both as a mother and a wife, losing her sense of self.

Overall, gender inequities are still an issue in Romania, and are represented in this new wave of cinema. Women can either be ‘manly women,’ who are trying to enjoy the same privileges as men, or ‘ideal women,’ who refute all of their dreams in order to become stay-at-home mothers and wives who run the household and let their husbands be the main providers. The fall of communism solidified the image of self-sacrificial women, a common gender stereotype too. The inequality showcased in the Romanian new wave films is still present; the only hope is that more and more women will join the film industry to help balance the representation of their gender in cinema while also using their position to tell the stories of women who haven’t escaped their traditionally oppressive roles yet.

The film Child’s Pose showcases the role of a mother who protects her son and the different gender roles in an unequal social structure. Although Cornelia did conform to the societal norm of being a mother, she did take her role in the household to a new level by being the authority figure over both of her male family members. Women are still represented in the film as being sacrificial; however there is this shift from mothers being heroic to being perceived as monstrous and maddening, and Cornelia is a prominent example of this. Throughout the process of trying to save her son from going to jail, Cornelia is rejected both as a mother and a wife, losing her sense of self.

Overall, gender inequities are still an issue in Romania, and are represented in this new wave of cinema. Women can either be ‘manly women,’ who are trying to enjoy the same privileges as men, or ‘ideal women,’ who refute all of their dreams in order to become stay-at-home mothers and wives who run the household and let their husbands be the main providers. The fall of communism solidified the image of self-sacrificial women, a common gender stereotype too. The inequality showcased in the Romanian new wave films is still present; the only hope is that more and more women will join the film industry to help balance the representation of their gender in cinema while also using their position to tell the stories of women who haven’t escaped their traditionally oppressive roles yet.

Works Cited

Baya, Adina, and Irina Diana Mădroane. “‘Should I Stay or Should I Go?’ The Promise of Europe and Female Identity in Francesca (2009).” Gender Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2019, pp. 96–112., doi:10.2478/genst-2020-0008.

Hornaday, Ann. “'Child's Pose' Movie Review: Romanian Thriller Is Compelling, Complex and Confounding.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 13 Mar. 2014, www.washingtonpost.com/goingoutguide/movies/childs-pose-movie-review-romanian-thriller-is-compelling-complex-and-confounding/2014/03/12/d39ebaea-a864-11e3-8599-ce7295b6851c_story.html.

Letitia, Manta. “Gender Representation across Political Regimes: a Comparative Analysis of Romanian Films”. Analyze: Revista de studii feminesite 6 (20):108-127

Nasta, Dominique. Contemporary Romanian Cinema: The History of an Unexpected Miracle. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Netzer, Calin Peter, director. Child's Pose. Parada Film Productions, 2013.

Pfeifer, M., Ribeiro, A. (2018, December 27). Ruxandra Zenide on Ryna. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://eefb.org/interviews/ruxandra-zenide-on-ryna/

Pier. “Romanian Culture - Family.” Cultural Atlas, 2021, culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/romanian-culture/romanian-culture-family.

Ribeiro, Ana. “Ruxandra Zenide's Ryna (2005).” East European Film Bulletin, 8 Dec. 2017, eefb.org/retrospectives/ruxandra-zenides-ryna-2005/.

Hornaday, Ann. “'Child's Pose' Movie Review: Romanian Thriller Is Compelling, Complex and Confounding.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 13 Mar. 2014, www.washingtonpost.com/goingoutguide/movies/childs-pose-movie-review-romanian-thriller-is-compelling-complex-and-confounding/2014/03/12/d39ebaea-a864-11e3-8599-ce7295b6851c_story.html.

Letitia, Manta. “Gender Representation across Political Regimes: a Comparative Analysis of Romanian Films”. Analyze: Revista de studii feminesite 6 (20):108-127

Nasta, Dominique. Contemporary Romanian Cinema: The History of an Unexpected Miracle. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Netzer, Calin Peter, director. Child's Pose. Parada Film Productions, 2013.

Pfeifer, M., Ribeiro, A. (2018, December 27). Ruxandra Zenide on Ryna. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://eefb.org/interviews/ruxandra-zenide-on-ryna/

Pier. “Romanian Culture - Family.” Cultural Atlas, 2021, culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/romanian-culture/romanian-culture-family.

Ribeiro, Ana. “Ruxandra Zenide's Ryna (2005).” East European Film Bulletin, 8 Dec. 2017, eefb.org/retrospectives/ruxandra-zenides-ryna-2005/.