Existentialism’s question was formulated as the question: what is the individual to do, faced with being in the world? Existentialism’s question was that of Dasein, that of essence and existence, of Being and of action. The Enlightenment raised reason to the Absolute, modernity steamed forward with impersonal progress; existentialism was formed from necessity, bringing philosophy back to the question of the individual. Now, existentialism has disappeared. Deconstructed, rejected, left behind; such a grand individualist and humanist doctrine has no place amid the posthuman and the postmodern. Yet, in such a time as this, existentialism’s question still remains, even more pertinent today.

Hungarian director Béla Tarr’s 2011 film The Turin Horse poses existentialism’s fundamental question; it does this in the historical contextualization of existentialism’s necessary moment: Fredicrich Nietzche’s proclamation at the end of the nineteenth century that ‘God is Dead’. In analyzing The Turin Horse, I intend to offer two major readings of the film, one from Nietzsche, the perspective the film alludes to, and one from contemporary philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Both thinkers enable an existential reading of the film, yet both thinkers radically differ. Nietzsche affirms the end of Christianity and humanism, embracing an atheist form of existential self-overcoming, while Žižek turns the very notions of both Christianity and atheism on their heads, recovering the Christian legacy as a necessary existential stance in the postmodern world of The Turin Horse.

Hungarian director Béla Tarr’s 2011 film The Turin Horse poses existentialism’s fundamental question; it does this in the historical contextualization of existentialism’s necessary moment: Fredicrich Nietzche’s proclamation at the end of the nineteenth century that ‘God is Dead’. In analyzing The Turin Horse, I intend to offer two major readings of the film, one from Nietzsche, the perspective the film alludes to, and one from contemporary philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Both thinkers enable an existential reading of the film, yet both thinkers radically differ. Nietzsche affirms the end of Christianity and humanism, embracing an atheist form of existential self-overcoming, while Žižek turns the very notions of both Christianity and atheism on their heads, recovering the Christian legacy as a necessary existential stance in the postmodern world of The Turin Horse.

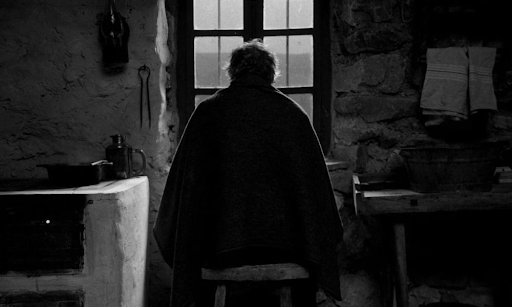

The exposition of The Turin Horse inflicts into the darkness of the opening shot the voice of narration. The narrator recites a story, a story from the history of philosophy. As it goes, in 1889 Friedrich Nietzsche stepped out of his door one morning onto the streets of Turin and went mad. As he walked toward the square, Nietzsche saw a cabman whipping his horse, he stopped him, throwing his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing and crying out “I understand you!” The exposition of The Turin Horse continues as the narration concludes, and the first real shot of the film opens on a horse drawing a cart, and a whip sitting next to the old driver. The following two and a half hours consist of thirty long, bleak takes in black and white, filled with single shot, ten minute long scenes of the old driver and his daughter repeating the same trivialities, again and again. The plot centres around their daily events in the same dark, stone house, set against the backdrop of desolate and empty farmland. The daughter helps clothe her old father, and he attempts in vain to get his horse to saddle up and move, resulting in long sequences of getting dressed and undressed, going in and out, eating and cleaning, and finally both the daughter and father sitting silently at the window looking at barren countryside, while the soundtrack repeats the same violin notes unendingly. Nietzsche is only mentioned explicitly at the very beginning, yet his reference echoes throughout the bleak imagery of the film. What the film depicts at its most basic level is the soul of man without God, the very essence of nihilism, and the very foundation for the question of existentialism.

Béla Tarr began making films in the ‘70’s. His arthouse, cinéma vérité style covers the mundane, the monotonous, and the nihilistic. The Turin Horse was his last film, and with it his last artistic message. In an interview on the film he recounts that he started out as a young filmmaker wanting to change the world. But, in his old age, he claims to realize that the same problems will always haunt us. For him then, The Turin Horse acts as his interpretation of Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return, that time is a flat circle, and all that has been done will be done before. In this way it would seem that the film bears no more than a hopeless message. But it must be clarified that, if this is taken as Tarr’s own interpretation of the film, it is a false one. Tarr is misreading Nietzsche’s concept. The eternal return for Nietzsche was the most profound existential revelation, not a nihilistic platitude. The eternal return was a concept that arose for Nietzsche when he asked what one would do if one was to live the same life again and again. This was his formula for self-overcoming, for existentialism: to live each moment always shifting, always creating, warlike and passionate, as if one had to repeat the same life willingly for eternity. The Turin Horse can be redeemed then from Tarr’s misinterpretation of Nietzsche. What Tarr does in the film is lay the foundation, through the bleakness of his visuals and through the minimalism of his script, for Nietzsche’s concepts to arise.

At the heart of the cinematic experience of the film is the aestheticization of Nietzsche’s infamous phrase ‘God is dead’. It is a visual and sensory depiction of all the mythopoetic historicity that is contained in that phrase, and it is this phrase that lies at the centre of Nietzsche’s anti-theological existentialism. We see in The Turin Horse that, before the death of God, man who lived in squalor could justify his toils by appealing to the backdrop of a God, but without God he is alone with his toils for the first time. The cinematography of the film shows the symbolic order structured by Christian values disintegrated, giving way to the drudgery of material existence. The important scene signaling the most explicit reference to Nietzsche is at the one hour mark. A neighbour comes to share a drink with the old driver. He sits at the table and ponders, saying that “everything has gone to ruin”. The neighbour explains ambiguously that there is talk of ruin and demise, rumours of the end of morals and a generation in despair. This makes an explicit reference to the death of God at the level of dialogue, and echoes the famous passage The Parable of the Madman from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, when a man comes to a village asking for God, but those he finds only inform him of His death. The literary consistency between this moment in The Turin Horse and The Parable of the Madman is a clear attempt by Tarr to reference Nietzsche both in style and text.

This poeticism in Nietzsche’s work, embodied in The Turin Horse, gives voice to what Nietzsche saw objectively in his time as the coming end of both Christianity and humanism in modernity. The background of the The Turin Horse is set against Nietzsche’s critique of these doctrines. For Nietzsche, there are a myriad of attempts in the western tradition to set man apart, or to confine him in some way. Christianity posited man as set apart from nature by God, and the Enlightenment posited man as set apart from nature by reason, sustaining the frame of Christianity while subtracting theism. This is a basic summary of the history of humanism. Nietzsche denies humanism, in his strongest posthumanist claim that

Béla Tarr began making films in the ‘70’s. His arthouse, cinéma vérité style covers the mundane, the monotonous, and the nihilistic. The Turin Horse was his last film, and with it his last artistic message. In an interview on the film he recounts that he started out as a young filmmaker wanting to change the world. But, in his old age, he claims to realize that the same problems will always haunt us. For him then, The Turin Horse acts as his interpretation of Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return, that time is a flat circle, and all that has been done will be done before. In this way it would seem that the film bears no more than a hopeless message. But it must be clarified that, if this is taken as Tarr’s own interpretation of the film, it is a false one. Tarr is misreading Nietzsche’s concept. The eternal return for Nietzsche was the most profound existential revelation, not a nihilistic platitude. The eternal return was a concept that arose for Nietzsche when he asked what one would do if one was to live the same life again and again. This was his formula for self-overcoming, for existentialism: to live each moment always shifting, always creating, warlike and passionate, as if one had to repeat the same life willingly for eternity. The Turin Horse can be redeemed then from Tarr’s misinterpretation of Nietzsche. What Tarr does in the film is lay the foundation, through the bleakness of his visuals and through the minimalism of his script, for Nietzsche’s concepts to arise.

At the heart of the cinematic experience of the film is the aestheticization of Nietzsche’s infamous phrase ‘God is dead’. It is a visual and sensory depiction of all the mythopoetic historicity that is contained in that phrase, and it is this phrase that lies at the centre of Nietzsche’s anti-theological existentialism. We see in The Turin Horse that, before the death of God, man who lived in squalor could justify his toils by appealing to the backdrop of a God, but without God he is alone with his toils for the first time. The cinematography of the film shows the symbolic order structured by Christian values disintegrated, giving way to the drudgery of material existence. The important scene signaling the most explicit reference to Nietzsche is at the one hour mark. A neighbour comes to share a drink with the old driver. He sits at the table and ponders, saying that “everything has gone to ruin”. The neighbour explains ambiguously that there is talk of ruin and demise, rumours of the end of morals and a generation in despair. This makes an explicit reference to the death of God at the level of dialogue, and echoes the famous passage The Parable of the Madman from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, when a man comes to a village asking for God, but those he finds only inform him of His death. The literary consistency between this moment in The Turin Horse and The Parable of the Madman is a clear attempt by Tarr to reference Nietzsche both in style and text.

This poeticism in Nietzsche’s work, embodied in The Turin Horse, gives voice to what Nietzsche saw objectively in his time as the coming end of both Christianity and humanism in modernity. The background of the The Turin Horse is set against Nietzsche’s critique of these doctrines. For Nietzsche, there are a myriad of attempts in the western tradition to set man apart, or to confine him in some way. Christianity posited man as set apart from nature by God, and the Enlightenment posited man as set apart from nature by reason, sustaining the frame of Christianity while subtracting theism. This is a basic summary of the history of humanism. Nietzsche denies humanism, in his strongest posthumanist claim that

no one gives man his qualities - neither God, nor society, nor his parents and ancestors,

nor he himself. (...) No one is responsible for man’s being there at all, for his being

such-and-such, or his being in these circumstances or in this environment. (...) Man is

not the effect of some special purpose, of a will, and end; nor is he the object of an

attempt to attain an “ideal of humanity” or an “ideal of happiness” or an “ideal of

morality.”

nor he himself. (...) No one is responsible for man’s being there at all, for his being

such-and-such, or his being in these circumstances or in this environment. (...) Man is

not the effect of some special purpose, of a will, and end; nor is he the object of an

attempt to attain an “ideal of humanity” or an “ideal of happiness” or an “ideal of

morality.”

From this quotation one can jump back into the world of The Turin Horse and see it reflected in the faces of the old driver and his daughter, stripped of their substantial meaning. Their characters contain no determination from God, nor any ideal. Their faces, pale as they lean upon the windowsill in the darkness, as they try in vain to saddle the horse, represent the universal image of man without ordained meaning. It seems as though Tarr’s interpretation of the film would leave the analysis here, but this is where Nietzsche answers this bleakness with a trumpet sound, a triumphant proclamation that with the expiration of the humanist doctrine

nobody is held responsible any longer, that the mode of being may not be traced back

causa prima, that the world does not form a unity either as a sensorium or as “spirit” -

that alone is the great liberation; with this alone is the innocence of becoming restored.

The concept of “God” was until now the greatest objection to existence. We deny God,

we deny the responsibility of God: only thereby do we redeem the world.

causa prima, that the world does not form a unity either as a sensorium or as “spirit” -

that alone is the great liberation; with this alone is the innocence of becoming restored.

The concept of “God” was until now the greatest objection to existence. We deny God,

we deny the responsibility of God: only thereby do we redeem the world.

For Nietzsche, the negation of a guaranteed, presupposed set of meanings for man was ultimately to be celebrated. The Turin Horse seems to dwell in this meaninglessness, but Nietzsche transcends this nihilism by turning it to a joyous acceptance of fate, amor fati.

In response to Nietzsche’s death of God existentialism, a Žižekian reading of The Turin Horse is needed. An examination of Žižek’s philosophy and its place in history, particularly Žižek’s reconceptualization of Christianity, will take the existential response to The Turin Horse further, making it even more relevant. Žižek agrees that Nietzsche’s death of God designates that Christian belief was in decay at the end of the nineteenth century, and that society was transitioning away from Christianity as the ultimate guarantee of subjective and cultural determination. But he does not regard Nietzsche’s open existentialism as the answer. In his affirmation of the death of God Nietzsche takes his existential stance on atheism. It is here that Žižek would make his critique. For Žižek, Nietzsche’s atheism is not the true atheism. Žižek is an atheist, yet unlike any other atheist he claims the only way to be a true atheist is to fully understand Christianity. Žižek not only sees the Christian legacy as holding an emancipatory political core, he also sees Christianity through a radical theological interpretation. According to his dialectical materialist reading of Christianity, in its retroactive historicity Christianity is actually profoundly atheist. It is this dimension that Nietzsche fails to see. According to scholars Dionysios Skliris and Sotiris Mitralexis

Christianity is for Žižek the religion of exiting religion; it is the last religion, and

Crucifixion, likewise, is not exactly a sacrifice but it is the sacrifice of all existing

sacrifices, the sacrifice which abolishes the sacrificial logic in its very depth.

Crucifixion, likewise, is not exactly a sacrifice but it is the sacrifice of all existing

sacrifices, the sacrifice which abolishes the sacrificial logic in its very depth.

For Žižek, Christianity ends the logic of religion. He posits this in his reading of Christ’s death. He sees the key to reading the atheism innate in Christianity particularly in the theological profundity of Mathew 27:26; Christ cries out “my Father, why have you forsaken me?” and it is here that Christ mirrors the heart of the human experience: we ourselves feel forsaken by God, and in this moment even God is forsaken by Himself; at this moment God Himself becomes an atheist. To Žižek this is the true death of God. The idea of God ‘up there’, the God of Beyond, the inaccessible, metaphysical conception of God, dies via the Crucifixion. In light of the Resurrection, the key passage for Žižek is Mathew 18:20 when Christ says to his disciples “wherever two or three shall gather, there I will be with you.” For Žižek, the second coming does not signify a physical return, but rather the Messianic course of world history as it points toward freedom. The Otherness of God is dead, Christ symbolically embodies and transcends the human experience, and the Holy Spirit is in fact just a metaphor for the community of believers alone with their freedom.

In this way, Žižek’s atheism does not reject Christianity as Nietzsche’s does, rather it sees as necessary the Christian experience and identification with Christ. Žižek turns Nietzsche’s existentialism on its head: Christ is the übermensch, precisely because he overcomes man, and we overcome ourselves via our identification with Christ. Through this identification we successfully pass through the curtain of belief to the freedom of true atheism. For Žižek, existentialism is embodied when we embrace the non-existence of absolute meaning, of God, accepting the concrete universality of our struggles in our particular historical moment. This dialectical logic cancels out Nietzsche’s unresolved and open existentialism.

In this way, Žižek’s atheism does not reject Christianity as Nietzsche’s does, rather it sees as necessary the Christian experience and identification with Christ. Žižek turns Nietzsche’s existentialism on its head: Christ is the übermensch, precisely because he overcomes man, and we overcome ourselves via our identification with Christ. Through this identification we successfully pass through the curtain of belief to the freedom of true atheism. For Žižek, existentialism is embodied when we embrace the non-existence of absolute meaning, of God, accepting the concrete universality of our struggles in our particular historical moment. This dialectical logic cancels out Nietzsche’s unresolved and open existentialism.

So how is the viewer to orient to The Turin Horse? In the last scene, the old driver and his daughter sit at their table as things fade to complete darkness. They do not touch the potatoes on their plates, succumbing to unspoken hopelessness. This final closing is the last bleak button on the film, representing what Nietzsche saw as a future leaning towards a collapse into nihilism. Through Tarr’s reading of the film, this moment is inevitable, the final fade into black signifies no final message. Through Nietzsche’s reading of the film, we must choose to accept this moment of nihilism or take it as an opportunity to go beyond this emptiness into an open existentialism. Žižek would refuse both these readings and put the imperative on the viewer: if we are to take the film as a radical metaphor for the contingency and meaninglessness of our lives under the consequences of history, we must refuse to accept our fate as the characters do. The characters in the end signify that they can no longer live with this negation of ultimate meaning, yet this is a mistake. In Žižek’s words,

although human subjectivity is not the origin of all reality, although it is a contingent

local event in the universe, the path to universal truth does not lead to the abstraction

from it (...) Since we are subjects, constrained to the horizon of subjectivity, we should

instead focus on what the fact of subjectivity implies for the universe (...) we are ‘universal

beings’ only in our fully particular engagements.

local event in the universe, the path to universal truth does not lead to the abstraction

from it (...) Since we are subjects, constrained to the horizon of subjectivity, we should

instead focus on what the fact of subjectivity implies for the universe (...) we are ‘universal

beings’ only in our fully particular engagements.

For Žižek, the radically existential stance of a Christian Atheist is to identify with the image of Christ, alienated from Himself on the cross, as we are alienated from ourselves, tarrying with the lack of guaranteed ultimate meaning. Universality is contained within our struggles, within our striving for Universality itself. Existentialism then is not the answer posited by The Turin Horse to the viewer, but the answer to The Turin Horse given by the viewer themselves.

Works Cited

Kohn, Eic. “Interview with Béla Tar”, Indie Wire, 2012

Nietzsche, Friedrich “The Portable Nietzsche”, edited by Walter Kaufmann, The Viking Press, 1954

Skliris, Dionysios, Mitralexis, Sotiris. “The Slovenian and the Cross” Slavoj Zizek and Christianity, Routledge, 2019

Žižek, Slavoj. “Afterword”, Slavoj Žižek and Christianity, Routledge, 2019

Kohn, Eic. “Interview with Béla Tar”, Indie Wire, 2012

Nietzsche, Friedrich “The Portable Nietzsche”, edited by Walter Kaufmann, The Viking Press, 1954

Skliris, Dionysios, Mitralexis, Sotiris. “The Slovenian and the Cross” Slavoj Zizek and Christianity, Routledge, 2019

Žižek, Slavoj. “Afterword”, Slavoj Žižek and Christianity, Routledge, 2019