Lorene Scafaria’s Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (Scafaria, 2012) combines two disparate genres; the disaster film and the romantic comedy. The psychological processes which bring out emotional responses from viewers are all at play here. The film uses music and color in particular to take viewers through the complete range of human feelings. It blends its two genres into an enjoyable experience but suffers from faults such as characterization problems and oversentimentality.

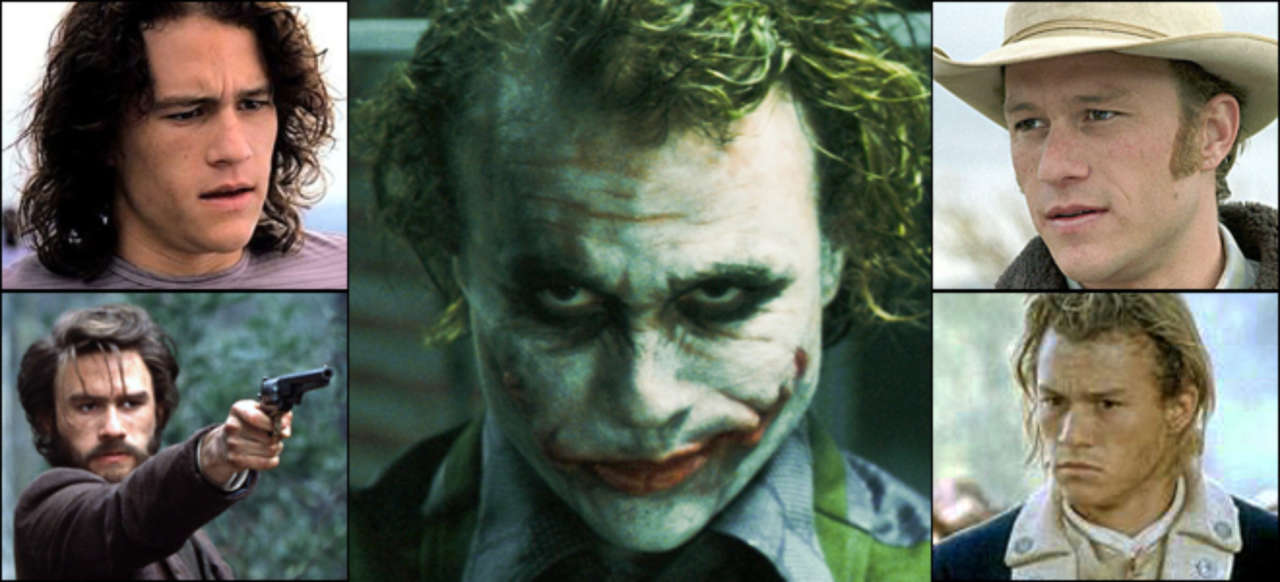

A photo collage of Ledger's most noteworthy roles (from Comicbook.com - http://comicbook.com/2015/01/22/heath-ledger-passed-away-7-years-ago-today/) By Megan Hess In 2018, it will be ten years since the passing of one of American cinema’s most promising foreign imports, a man whose career was characterized by variety. Over the near-decade Heath Ledger worked in the US, he dabbled in a variety of different genres - Shakespearian adaptations, historical dramas, biopics, and superhero films, to pick a few of the most notable genres in his filmography. In his biographical piece for New York Magazine written after Ledger’s death, Chris Norris calls him, “a probing and adventurous character actor—someone who said he had purposely “taken the blonde out of his career” - meaning, he wanted to distance himself from the “pretty-boy” image that his American debut, 10 Things I Hate About You (Junger, 1999), brought him (1). Despite the supposed randomness in his selection, Ledger seemed continually drawn to roles that dealt with the effects of hypermasculinity on men – parts that portrayed characters boxed in by the way society tells men they should be. He hardly ever played the regular guy, but always fell into overtly masculine archetypes: the juvenile delinquent, the cowboy, the soldier, the knight, the musician. These social roles influence what people think about men and how they perform gender. If gender and gender roles are a spectrum, as many believe, with “masculine” at one end, and “feminine” at the other, men who occupy these roles are expected to be all the way over on the “masculine” side, exemplifying manhood. That is why I use the term “hypermasculine” during my analysis. Ledger’s ultra-manly roles started before the two films he is most famous for, the ones which will be the primary focus here: Brokeback Mountain (Lee, 2005) and The Dark Knight (Nolan, 2008). In fact, his American breakout – the one which got him labeled as just another hunky young star - began the pattern. In 10 Things I Hate About You, a modernized teen adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, Ledger plays Patrick Verona, a tough young man shrouded by cigarette smoke and crazy rumors (“I heard he ate a live duck once,” one character says to another. “Everything but the beak and feet,” the other responds) - the basic teenage delinquent archetype complete with long hair and a black leather jacket. As such, the main male characters are afraid to approach him at first, but, as both the viewers and Kat Stratford (Julia Stiles), 10 Things’ female lead, discover, he is more capable of great sensitivity than sadism – a person to trust, rather than fear. Patrick's relationship with Kat (Julia Stiles) brings out his goofy, sweet, side (10 Things I Hate About You, Junger, 1999) The conversation about male identity that starts in 10 Things... carries over into Ledger’s later films. Brokeback Mountain exemplifies the archetype of hypermasculine man with a hidden\inaccessible emotional core, and is the most self-aware of the damage that comes from societal pressure, especially of this variety. Annie Proulx, who wrote the short story the film is based on, chafes against the “urban critics’’” description of the film as “a tale of two gay cowboys” (Proulx 131) because of how that label sidesteps the “destructive rural homophobia” Proulx believes is the pulse of the narrative– a “destructive rural homophobia” that goes so deep the characters inflict it on themselves (Proulx 130). After their first sexual liaison, Ennis (Heath Ledger) tells Jack (Jake Gyllenhaal) “It’s a one-shot thing we got going here” and “I ain’t no queer;” Jack responds to the latter with “Me, either” (McMurty and Ossana, 20). Neither character intends to take that sexual relationship off the mountain, but, as Proulx says “they both fell into once-in-a-lifetime love” – albeit a “once-in-a-lifetime love” they cannot express to the broader society (Proulx 130). Ennis and Jack are very much constrained by their culture and what it expects of them as men: both sexually and emotionally. Proulx praised Ledger’s performance, saying he “knew better than I how Ennis felt and thought” and his “intimate depiction of that achingly needy ranch kid builds with frightening power” (Proulx 137). While Jack is not unusually emotional for a man of that time, he is a little freer with his feelings than Ennis – partly because he’s more talkative. But for what Ledger’s character lacks in emotional expressiveness, he makes up in emotional intensity. Much like Lee Chandler, Casey Affleck’s Oscar-winning protagonist from Manchester by The Sea (Lonergan, 2016), Ennis is harboring a lot of deep and strong feelings, but has no idea how to bring them to the surface – at least, not in a healthy way. He channels them all through the conduit of anger, and goes from punching walls to other people. He never hits his wife, Alma (Michelle Williams) but drives her away with that same anger, expressed alternatively in words and silence. He uses it to keep Jack at a distance – always shutting him down when he tries to broach the idea of them getting a ranch together – and it almost brings their relationship to an end. Annie Proulx’s character – and Heath Ledger’s interpretation of him - may be a fiction, but the way he handles his emotions is all too true to life. Even when in the company of his greatest love, Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger, right) looks pensive - like he's feeling a thousand different things, but just doesn't want to emote them - and doesn't know how (Brokeback Mountain, Lee, 2005) Several years after Brokeback Mountain, Ledger picked up a role entirely different from those preceding it, and the one that would become his most iconic. Ennis Del Mar is driven by his fears, feelings, and relationships, but the Joker has no such motivations. As Alfred (Michael Caine) says in the film “some men just want to watch the world burn” (Nolan et al. 229). As a result, he has no ties. Most young male audience members can’t relate to the Joker, but they do admire him. He cares about nothing but himself, and, as a result, is unaffected by the culture and its requirements for those in male bodies. While the Joker possess many negative attributes that would be worrisome for viewers to aspire to adopt (mainly his total disregard for the value of other human lives), it also says a lot about the way our society is constructed that young men yearn to be like the Joker just to have his freedom. As the Joker, Ledger personifies chaotic apathy - and, therefore, the ideal of culturally constructed masculinity (The Dark Knight, Nolan, 2008) Hypermasculinity does not just affect the films that Ledger had made, but also the films he would have made. Little known to most, Ledger had directorial ambitions; the first film he wanted to make would have been an adaptation of Walter Tevis’s 1983 novel The Queen’s Gambit. As well as directing, Ledger also intended to star in the film…but he would not have been the lead. The Queen’s Gambit is the story of a young woman trying to make her way in the male-dominated world of chess. In that way, it both reflects the dominant themes in Ledger’s filmography, but yet subverts them. As one of the only women succeeding in chess at the time, Harmon is a pawn of toxic masculinity – a woman very aware of her femaleness in a predominantly male space - but she never lets it pull her under. How aptly this mirrors Ledger’s life! The exact circumstances of his death are murky even to this day; in her article for Wired on Ledger’s post-mortem medical examiner’s report, Kirsten Philipkoski calls the combination of drugs that killed him “unnecessarily dangerous,” and doubts a doctor would prescribe that many of those kinds of medications all at once (1). It is impossible to know how much the roles he had to play took a toll on him. Perhaps Ledger struggled with the very cultural push-and-pull he portrayed so well onscreen….

Regardless of his career’s impact on his personal life, the imprint Ledger left on the industry is clear. No actor living and working today displays the complications of manhood in quite the same way, nor quite so well. Works Cited -- “Brokeback Mountain: A Screenplay.” Proulx, pp. 29-128 Nolan, Jonathan and Nolan, Christopher. “The Dark Knight.” The Dark Knight Trilogy, edited by Christopher Nolan, Jonathan Nolan, and David S. Goyer, OPUS, 2013, pp. 167-323. Norris, Chris. “(Untitled Heath Ledger Project): Analyzing the Double Life of Heath Ledger” New York Magazine. 18 February 2008 http://nymag.com/news/features/44217/ Accessed 7 March 2017. Philipkoski, Kristen. “Unnecessarily Dangerous Drug Combo Caused Heath Ledger’s Death.” Wired. 6 February 2008. https://www.wired.com/2008/02/accidental-over/ Accessed 3 March 2017. Proulx, Annie, McMurtry, Larry, and Ossana, Diana, editors. Brokeback Mountain: Story to Screenplay. Scribner, 2005. -- “Getting Movied,” McMurtry and Ossana, pp. 129-138 David (Colin Farrell, far left) and the other Hotel guests on the bus to go hunting (Lanthimos, 2016). by Megan Hess We live in a world that encourages romantic and marital partnerships. Our entertainment media usually has romantic subplots, and books and movies focused solely on romance typically do very well. Married couples get legal, economic, and social rewards that couples who are only dating or living together do not. These and other factors contribute to the societal idea that people’s lives are better when they are in a monogamous relationship than seeing several people at once, or not seeing anyone at all. But, what if, instead of just implying that being romantically attached was superior, society directly discouraged singleness - if it offered up an ultimatum: find a mate in a prescribed amount of time, or lose your humanity? The Lobster (Lanthimos, 2016) operates on this spellbinding premise. Divorced or otherwise single people get shipped off to an upscale hotel designed for the purpose of obtaining a life partner. Once there, they have 45 days to find a compatible mate. If they do not accomplish this objective within the 45-day period, they will be turned into an animal of their choosing. Such a zany, captivating, premise could crumble if mishandled, but, as interpreted by Lanthimos and his team, it’s successful - an unflinching, dark-humored, cynical social commentary on romance and companionship. An innovative plot can only get a filmmaker so far. The Lobster persists beyond attention-grabbing summary because of its relatability. No matter how far it ventures into the bizarre, it remains true to life. The Lobster creates this effect from the beginning in myriad ways. Casting choice is a significant one. The main players are fringe names – actors who have been working in the industry a long time, but do not have the household presence or star power as, for example, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt do in America. Casting big names in a picture is usually a good marketing strategy, but it is not always the best artistic choice. In fact, it can often work against a director’s favor because the audience is unable to detach the stars from their previous roles. The Lobster does not have that problem. It has a wealth of great character parts, and the actors in those roles are well-suited to them. Rachel Weitz, as the Short-Sighted Woman, delivers a standout performance (The Lobster, Lanthimos, 2016) As well as avoiding Hollywood elites, The Lobster steps away from Hollywood body types…for the male characters, at least. All of the film’s major female characters except The Biscuit Woman (Ashley Jensen) are classically beautiful. I found this not only unrealistic, but at odds with the rest of the movie. The Lobster is not a film that celebrates beauty. Conversely, The Lobster wraps itself in bleak pessimism, with a scrim of discomfort. Happiness and love do not come easily. For some, they do not come at all. The Lobster does not fit all people’s definition of an enjoyable cinematic experience, but it is an important one – director\screenwriter Yorgos Lanthimos’ first film in English. I believe it was significant that Lanthimos chose not to make this film in his native language, Greek. The Lobster distinctly reflects American values and way of being. Lanthimos’ distance from American society allows him to see it with clearer eyes than an American director who’s enmeshed in the various cogs and gears might. He has created a rich, dark, unforgettable satire. David dances with the Nosebleed Woman (Jessica Barden), one of his potential matches (The Lobster, Lanthimos, 2016) Part of what makes The Lobster so memorable is all it leaves unknown. Unlike other dystopian dramas - both far-removed and recent - it does not provide exposition for why society picked up this practice. The process of turning humans into animals is never explained, either. The most irritating mystery is the specific details of David’s (Colin Farrell) revenge on a woman who has wronged him – second, of course, to its ending - which Entertainment Weekly calls “beautiful” and “elliptical” – (McGovern 1). The ending of the Lobster is reminiscent of a staple of high school English programs: Frank R. Stockton’s “The Lady or the Tiger?” – not in content but in its potential to provoke bewilderment in the viewer. As such, I would recommend not watching The Lobster unless you have a good half-hour or more to devote to developing your opinion of what happens after the final shot. For every argument, a potential counterpart emerges – but it’s a debate you won’t regret having, whether alone or with friends.

As highly as I praise The Lobster, I admit it might not be the best film for everyone. If you're a soft-hearted, easily nauseated, animal-loving, blockbuster fan, you might want to pass this one by. However, for those who choose to watch, it will be one of the best films you have ever had the chance to enjoy. The Lobster puts Lanthimos in the same class as Asghar Farhadi - a foreign director with crossover appeal, a talent too good to be hoarded by his home country. His next film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, comes out next year. Will it be as good as The Lobster? It's too soon to tell, but there's a good chance.... Works Cited McGovern, Joe. “The Lobster: Colin Farrell shares his (spoiler-free) thoughts on the film’s ending.” Entertainment Weekly. 16 June 2016. http://ew.com/article/2016/06/06/colin-farrell-lobster-ending/ Accessed 26 February 2017. By Perri Chastulik From conventions to fanfiction, fans of any TV, movie, or book series can engage in activities “outsiders” may find puzzling. One such practice is “shipping,” or wanting two characters who are not romantically involved (or sometimes not even from the same universe) to get together (Kircher, 2017). As Abby Norman’s enlightening article from The Mary Sue points out, analyzing forums like Tumblr proves even fans ask themselves if shipping makes them “weird” (Norman, 2015). However, there are psychological reasons for the phenomenon, which the 2013 film Hitch (Tennant, 2005) explores. |

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed