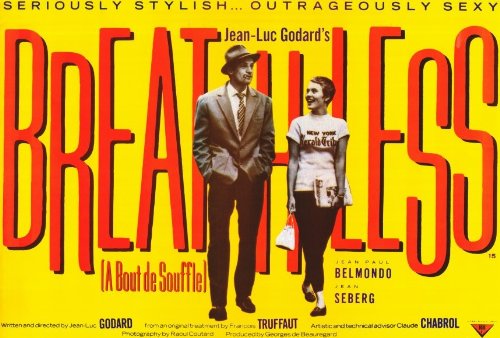

The film is not only revered for its intense plot, but for its stylistic acting and editing techniques too. Throughout, there are many long takes in which the actors improvise off of one another and, at times, it is edited with numerous jump cuts that cue “jump forwards” in time have occurred and that are able to create a rich and full story for the audience to dive into.

The strange and innovative techniques that were established in this film have given it the reputation of one of the classics of world cinema.

The opening frame of the film is dedicated to Monogram Pictures, a production company that is well-known for creating and releasing B-movies such as Montana Incident (1952, dir. Lewis D. Collins), a famous Western about two railroad surveyors, and Suspense (1946, dir. Frank Tuttle), a noir-drama about a man who works for an ice-skating magnate.

Godard could have included this frame for a multitude of reasons: he might have been paying homage to the company itself for releasing movies that could be seen as subpar and giving them the credit they deserve, or he might have also put it in as an Easter egg for film buffs, to make them excited about the story to come. Personally, I believe that Godard added these frames because of the former: Monogram Pictures was known for not making ground-breaking films, and its placement at the beginning of the movie could be a subliminal message. One of the most important aspects of watching a movie, in order to enjoy it, is by going into it with the right mindset. When people go into a Hollywood movie, they do so certain expectations, and if those expectations are not met, they will most likely leave the theater feeling disappointed.

By referencing a B-movie company right away, the director might have been trying to get the audience to subtly think of the film as being on the same level as a B-movie without them realizing or trying to make a commentary on B-movies in general. This way, the viewers would’ve gone into the movie with a lower set of expectations, causing its appeal to strike a wider audience.

If, however, it is the latter option, Godard might have just had a great deal of respect for cinema and Monogram Pictures in general, and wanted to show his appreciation by paying homage to it at the beginning of his own work.

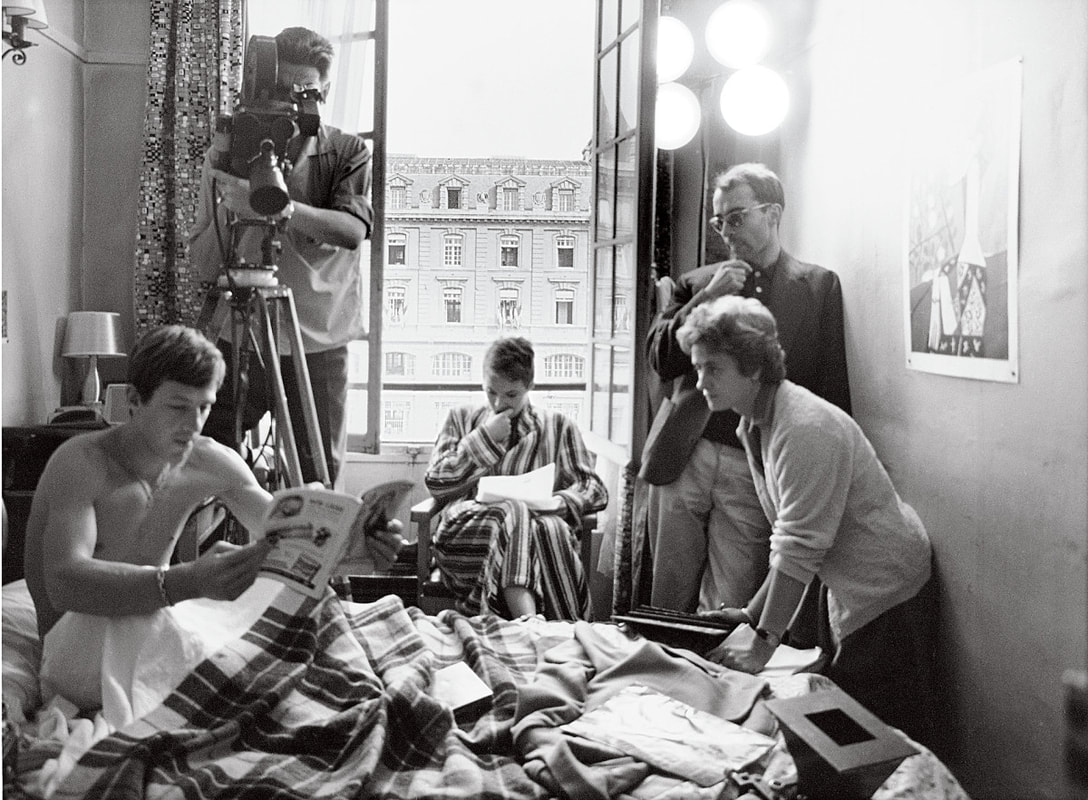

Overall, I do not believe that Godard went into creating this film with the goal of violating filmmaking conventions as a way of creating shock and surprise. If he wanted to do so, he could have gone and pushed the limit much further than how he ended up doing. However, as it turns out, it was not in Godard’s original plan to implement the editing technique that made Breathless so widely known. “His jump-cut technique […] like most innovations, it came about accidentally: the rough cut was too long, and Godard and his editors hit upon the idea of snipping out the extraneous linkages in storytelling” (Rainer 1).

Despite all the praise the film and those who had worked on it received, the jump cuts were never actually something that was planned, but rather decided upon in the last stage of post-production. So, Godard did not set out to try to purposefully mess with his audience: he did so in order to adhere to the runtime requirements. In the long run, the decision ended up being extremely productive for the crew due to the massive turnout the film has received over the years. They were able to create a new technique of filmmaking and a different take on storytelling while still keeping a cohesive plot.

The way in which Godard and his crew made this film incoherent-like almost reflects the way of the environment at the time: “[T]he French [...] tend to be drawn to ideas, while the English [United States] distrust them, with the result that English art is often less intellectually informed than one would wish” (Cohen). When viewing the film, keep this in mind: it makes sense for the plot and acting to not be always straight-laced, as they were never meant to be.

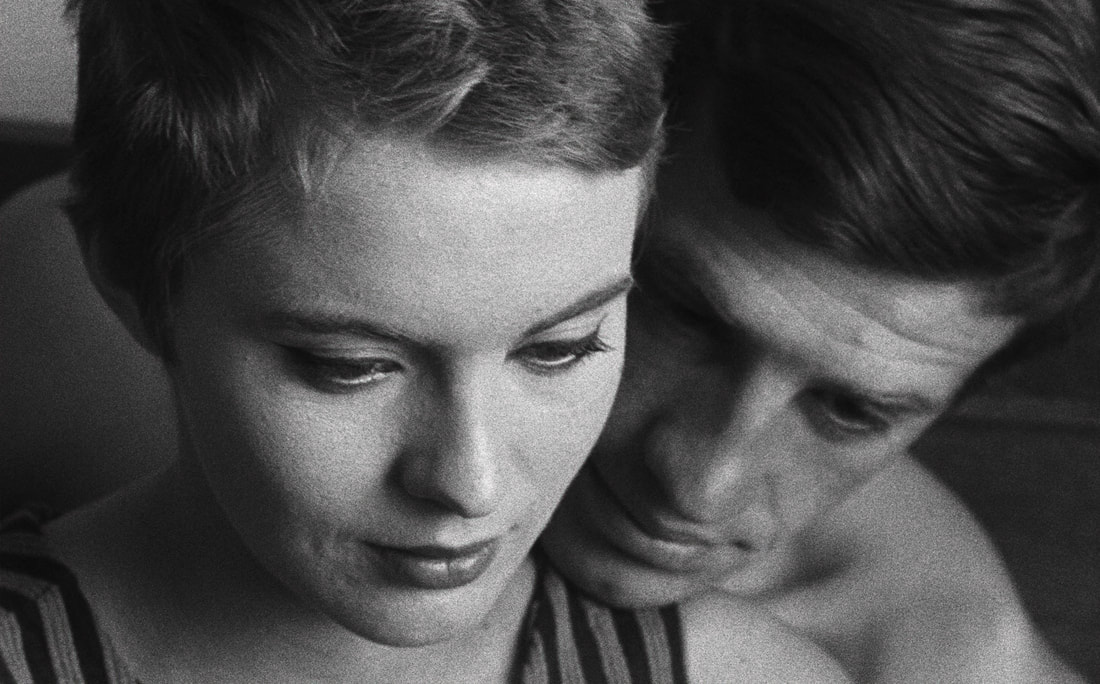

Similarly to the rough jump cuts throughout the film, the editing is not the only aspect of Breathless that stands out: the performances from the main actors are not what one would classify as following the traditional standard of characterization and acting.

The most obvious way in which the two actors depart from the standard of acting is that there are many scenes in which the two engage in improvisation. With improv, actors have little to no rehearsal because it is something that has to come in an instant. With the newly created lines, the other actor has to make split-second decisions on how to emote and what their next line should be. Without the use of a script, the activity is no longer “typical” acting, but whatever the actors can think up on their own. The dispensation of rehearsal in favor of improv causes two major problems that can make the acting unrealistic.

The second major problem that can result from doing improv is that there is no guarantee that what is said will connect to and support the plot. The greatness of screenplays is oftentimes based onto the fact that every aspect of it either factors or plays an important part in the story. If the actors have to improvise the majority of their lines, there is a good chance that all the acting will do is merely pad out the runtime while adding nothing meaningful to the plot.

On the other side of the argument, the improvisation might benefit the film in that it is not traditional and will make itself stand out amongst other films of that time (and even today).

However, while Godard allowed his actors to interpret their lines as they wished, he did have a plan to keep the story on track. “Coutard [the cinematographer] has stated that the film was virtually improvised on the spot, with Godard writing lines of dialogue in an exercise book that no one else was allowed to look at. Godard would give the lines to Belmondo and Seberg while having a few brief rehearsals on scenes involved, then filming them” (Matthew).

By giving his actors notes, Godard was able to keep a form of consistency to the plot while keeping that “natural” feel of improvisation.

Long takes are typically employed so that the audience can have a better understanding of the environment, the characters, and the plot while providing a more realistic take for the viewers, while jump cuts remove aspects from the plot, giving the impression that there is a hole in between shots, causing a sudden change that ignites feelings of confusion and agitation. By choosing to film and edit this way, Godard presents a stark contrast between the scenes in which these techniques are employed, and forces the audience to pay closer attention to what is and isn’t important.

When considering wherever Breathless contains anything realistic or not, the answer to that is definite: certain aspects of the plot are heavily influenced by real-life events. Francois Truffaut, a collaborator of Godard, “[H]ad been inspired by a true story that had fascinated tabloid France in 1952, when a man named Michel Portail, a petty criminal who had stolen a car, shot a motorcycle policeman who pulled him over, and then hid out for almost two weeks [...]. Portail had an American journalist girlfriend who he had tried to convince to run away with him” (Hitchman and McNett). So while the more specific details of what happened when portail was in hiding and the conversations he had with others may not be an exact replica of what truly occurred, the basic concept of the man is inspired by a news story from the time.

Godard’s fascination with the idea of life as depicted by the medias is what inspired the story based on real events mixed with fictional overdramatization. While the news does report on events, some tend to tell only the more dramatic aspects, overexaggerating them too in order to increase viewership, a style and tone of storytelling that Godard wished to replicate with his film.

Despite it being over sixty years old, Breathless should still be considered by today’s viewers an innovative and dynamic piece of cinema. Wheeler Winston Dixon claims that: “Seen today, Breathless seems primitive, classic, not at all the audacious ground-breaker it seemed to be in 1959. The jump cuts which were so radical then are now a staple of MTV.” There are many flaws that can be pointed out in Dixon’s argument. His reasoning as to why Breathless can no longer be seen as innovative hinges on the belief that, because the techniques that made the film stand above the rest during its time are now seen on the average television program and have become basic methods that are frequently utilized, then they make the film lose all the creativity and innovation it held in the past.

These films should not be insulted because their techniques have become mainstream, but praised for it. Because of the crews who worked on these films, people today have so many more tools in their arsenal to make great movies. Dudley Andrew makes an interesting point when he states that “Breathless belongs to that very short list of films that stunned audiences in their own time and continue to stun us today.” While the utilization of jump cuts is much more prominent in today’s time, I cannot recall a film or television show that has implemented them in the same way as Breathless. Watching this film was a bizarre and wonderful experience, and it still stuns me with the creative choices that were settled upon.

- Cohen, Paula Marantz. “The Potency of ‘Breathless’: At 50, Godard's Film Still Asks How Something This Bad Can Be so Good.” American Scholar, vol. 78, no. 2, 2009, pp. 110–114., https://doi.org/https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=4&sid=4e3b2825-f286-4a51-bce1-bf5edd6ce209%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=37155447&db=asn.

- Hitchman, S, and A McNett. “Breathless (a Bout De Souffle) - Jean-Luc Godard.” Newwavefilm, http://www.newwavefilm.com/french-new-wave-encyclopedia/breathless.shtml.

- Irwin, William. “What Is an Allusion?” Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism, vol. 59, no. 3, Mar. 2001, https://doi.org/https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=11&sid=cefa381d-2bc9-476b-bd80-cb4c2b483caf%40redis.

- Matthew. “Breathless (1960).” Classicartfilms, http://www.classicartfilms.com/breathless-1960.

- Rainer, Peter. “Breathless: Movie Review.” Christian Science Monitor, June 2010, p. 1.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed