The Hunt is a film about rich people (i.e. hunters) hunting less wealthy people (i.e. hunted) for sport. A text chat of the hunters talking about Manor House, the facility where The Hunt takes place, is the inciting incident for the film’s events. The first and second act contain the deaths of many characters, while giving hints to the hunter’s motivation. It comes a question of what is real and who is trustworthy. The film enters the 3rd acts as Crystal (the last hunted played by Betty Giplin) and Athena (the last hunter played by Hillary Swank), choose to fight to the death. The hunter’s motivation is revealed during their struggle. As it turns out, the public started theorizing about Manor House when the text chat was leaked to the public. The public had reason to believe that Manor House is a real place. Thus, Athena and her friends devised a plan to capture these “theorists,” and kill them at Manor House. In other words, the hunters joked about Manor House being real in the chat, therefore making it a reality because the public talked about it. As Athena explains it, they (her and her friends) made Manor House a killing ground (where before it was simply Athena’s vacation house) because the public (i.e. people posting about it online) wanted it.

|

By Sammi Shuma Coming out of the theater for this film, I couldn’t really remember what I just saw. Was I not paying attention or did the film’s message not grab my attention? I find that it’s the latter. There is some message The Hunt wants movie goers to engage in, but the film’s execution prohibits the intake of that message. This stems from a few things, mainly the characters and writing. These two elements make up the main chunk of any film, they are the foundation to creating a message. A film’s special effects and imagery can be impressive (as this film tends to be), however without proper writing and characters, movie goers leave the theater with a faded memory of the film. Please be advised that the remainder of this review will contain spoilers. The Hunt is a film about rich people (i.e. hunters) hunting less wealthy people (i.e. hunted) for sport. A text chat of the hunters talking about Manor House, the facility where The Hunt takes place, is the inciting incident for the film’s events. The first and second act contain the deaths of many characters, while giving hints to the hunter’s motivation. It comes a question of what is real and who is trustworthy. The film enters the 3rd acts as Crystal (the last hunted played by Betty Giplin) and Athena (the last hunter played by Hillary Swank), choose to fight to the death. The hunter’s motivation is revealed during their struggle. As it turns out, the public started theorizing about Manor House when the text chat was leaked to the public. The public had reason to believe that Manor House is a real place. Thus, Athena and her friends devised a plan to capture these “theorists,” and kill them at Manor House. In other words, the hunters joked about Manor House being real in the chat, therefore making it a reality because the public talked about it. As Athena explains it, they (her and her friends) made Manor House a killing ground (where before it was simply Athena’s vacation house) because the public (i.e. people posting about it online) wanted it. This reasoning, boiling down to “you wanted it, so I gave it to you,” makes no sense. Who in their right mind would think that people want a killing ground to be real? Just because people theorized and talked about it doesn’t mean they wanted it to be true. People theorize about horrible things all the time, but it only means they think it’s real, not that they want it to be real. The text chat was enough evidence for people to suspect the worst. Even if the theorists wanted Manor House (as the killing ground) to be real, what is motivating Athena to make their desire a reality? For a character to be compelling, they must be motivated by something that is relatable in some way. The audience doesn’t have to agree with how the character is driven if the audience can understand how that character reached their motivation. Athena doesn’t get anything out of hunting down these people. She isn’t doing this to get a reward, or money, she doesn’t get satisfaction from it either. Athena didn’t even earn the right to be vengeful (if that’s what the film is going for) because she didn’t struggle throughout the film. Why spend all these resources to hunt people who impact you in almost no way what so ever? This could be excused by Athena’s possible insanity, but all her friends were motivated by this reasoning too. Character motivation is crucial when filmmakers want us to care and relate to their characters. We don’t have to like a character or agree with a character’s motivation, we will care about what is happening in the movie if it makes sense. Throughout The Hunt, the audience has no idea why they are on a killing spree. Hints are given throughout, leading us down a path of mystery and intrigue. It gave viewers a reason to keep watching, as a means to understanding the “villains” of this movie. All hope of this film being interesting was lost when Athena explained her motivation. The Hunt’s story and characters have no time to be interesting. A large majority of the film’s characters die before the end of the first act. Meaning the audience never had a chance to care about half of the film’s characters. We had one scene of the hunters (not including Athena) talking before they were killed by Crystal. Again, nearly another half of the film’s characters are dead before we can care about them. Leaving Athena, Crystal, Gary, and Don. Athena is motivated by something that doesn’t make sense. Crystal is mistrustful, so she never discloses any of her personality on screen. Although she has the most screen time, her main character trait (i.e. not trusting others) prohibits the audience from understanding her. Gary and Don (men who accompany Crystal throughout the film) are caricatures of middle-aged American men and die before they can grow out of that stereotype. The film has too many dispensable characters, meaning a lot of screen time is wasted on things the audience doesn't care about. When a film focuses on characters they not relatable, the message is lost as well. If there was meant to be a message about American politics and a comment of how people treat each other, it was lost because the characters didn’t enforce that message in a meaningful way. In closing, this film is easily forgettable. It promised so much mystery, but its buildup fell flat. With no redeeming qualities in the film’s characters, I gave up. The visuals and special effects are impressive, they make the action and destruction in this film feel real. However, those are mere additions to the film and do not save the story. If you are looking for an action movie to watch on a Friday night, you're welcome to view this movie. All l I can say now is that you will leave the theater learning nothing and remembering The Hunt as if it were a distant memory.

By Ravi Ahuja Autumn de Wilde’s directorial debut is not getting a lot of mainstream attention, and that’s a shame. I never expect too much out of a first-time director, but I was intrigued when I saw the trailer for Emma, which seemed to promise Downton Abbey social politics with a Wes Anderson color palette. While the film does suffer from some slight clarity and pacing issues in the beginning, it does deliver on that promise with some truly carefully composed cinematography. The film centers around Emma Woodhouse (Anna Taylor-Joy), a 19th-century British socialite with a penchant for high society matchmaking. When her governess marries out of her house, she decides to take on Harriet Smith, a local orphan girl as her protege. Despite initially promising not to interfere with her love life, Emma can’t help but secretly manipulate things with the intent of helping. Through the consequences of her actions and the blossoming of her own love life, she matures into a more thoughtful and selfless young woman. Although this is Autumn de Wilde’s first feature film, she has been a photographer specializing in album covers for the past three decades, and it really shows with her set design and her establishing shots. The costumes are kept fresh and surprisingly fun throughout, with a wardrobe consisting mostly of pastels and primary colors. Throughout the film, there are a number of absolutely gorgeous long shots utilizing a mixture of natural settings and classical architecture to create a composition that feels straight out of a renaissance painting. In fact, Emma has a close connection with classical art in general, with several scenes featuring huge, room-size paintings prominently in the background, occasionally framing characters in the movie as a character in the painting. Of course, the classical soundtrack composed by Isobel Waller-Bridge deserves a mention as well. The neo-classical style at the beginning fits well with the charming and clever character that Emma is made out to be and slowly changes throughout the movie to be more emotional, melodic, and dramatic, maturing throughout the movie along with Emma. The movie does have some issues, primarily in the first act. While I do appreciate when a film doesn’t hold the audience’s hand and allows them to infer what is going on, the relationships between characters took longer to understand than it felt like was intended. It was especially hard to deal with due to the amount of social politicking taking place, so the true motivations of each character were a little confusing until later on in the film. While this may have been intentional to some extent, the first act felt just a bit needlessly confusing. Another slight issue was with the cinematography of the dialogue scenes. A large portion of the movie was scenes of characters just sitting down and talking to each other, and these scenes were far less visually inspired than the rest of the movie. Yes, it is harder to make a five-minute dialogue scene look as beautiful as an establishing shot, but the repetitive shot-reverse-shot structure of these scenes felt a little too generic for a film that is otherwise so beautiful. All in all, Emma is still worth checking out for anyone who likes social dramas, period pieces, or just a visually beautiful movie.

By Daniel Sison When it comes to Japanese Animation, otherwise known more commonly as “anime”, there is one genre that overshadows the rest. This genre is referred to as “Shonen”. After searching “top 10 anime” in Google, results show that eight of the ten anime listed by Google fall under the category of “Shonen”. But, what is this genre? And what is so special about it? The word “Shounen” (少年) in Japanese means “boy”. Similarly, the genre of shonen is specifically made for boys in their teens or younger. Because of this, shonen anime usually focuses around the theme of friendship, youth, and power. Most shonen anime depict their main character banding with a bunch of friends and coming together to defeat enemies. In other words, friendship and youth lets the main character gain enough power to defeat an even more powerful enemy. My Hero Academia (僕のヒーローアカデミア), directed by Kenji Nagasaki in 2014 is a Japanese animated TV series that falls right under the category of shonen. At the time of its release, it struggled since it had to compete with other shonen anime that were extremely popular. However, My Hero Academia quickly gained popularity since it was new, and many people who had never seen anime before began to watch this show. Like other anime shows, the series emphasized the following themes of friendship, youth, and power. Recently, Kenji Nagasaki directed a movie that explores a subplot within the realm of My Hero Academia. Released on February 26, 2020, thousands of My Hero Academia fans went to watch the movie - My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising. The movie, even more than the show, accentuates the classic shonen themes. It even follows the same plot techniques; the only difference is that the duration of the movie is about one hour and forty-five minutes, while the duration of the entire series combined is more than twenty-six hours. My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising follows the TV series, which takes place in a world where people have superpowers, called quirks. Quirks are vastly different and can be hereditary. Both the movie and the series focuses on the life of Deku, a student with green hair at U.A. Highschool, where superheroes are raised and trained. However, Heroes Rising takes place not at the school, but on the island of Nabu, where Deku and his classmates are posted for training. According to the teachers and the heads of U.A., no villain has appeared on the island for years. Unfortunately for the novice heroes, a group of villains appear on Nabu, and without any help from professional heroes, they have to find a way to stop them. What’s worse is that the main villain is extremely overpowered since he possesses six different quirks. The power system is what makes the shonen genre so exciting. In almost every shonen anime, the main character is extremely weak in comparison to the villain. In other words, the main character is usually the underdog. This power dynamic is what makes sports so interesting. For example, in football, if an underdog team wins the superbowl, all of the fans go crazy. Similar to sports, when something impossible becomes possible in a story, it becomes more interesting. This is why the antagonist of My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising fits so perfectly within the genre of shonen. With six different quirks, he seems unstoppable. In comparison, Deku is just a small, teenage boy aspiring to be a hero. As a child, Deku was one of the 20% of people born without a quirk. Since he was quirkless, he was bullied his whole life. This plot element allows the audience to empathize with Deku and cheer for him. Eventually, when he does receive a quirk, he has no mastery over it, so he has to learn how to use it. Against the seasoned veteran antagonist, Deku appears small and powerless. However, Deku has amazing mental fortitude. This characteristic is shared by main protagonists of other shonen anime, such as Haikyuu (Susumu Mitsukana, 2014), or Attack On Titan (Tetsuo Haraki, 2013). Whatever happens, the protagonists of these anime never let anything discourage them. In the same way, even when Deku was powerless and quirkless, he never gave up. This is why the shonen genre is so inspiring. Even when it seems hopeless, through hard work and positivity, the good guy always wins. In the second half of the Heroes Rising, Deku’s classmates split up into groups of four or less, and each team battles a villain. Again, there is an emphasis on the theme of “friendship”. With friendship and coordination, each team manages to pull out a miracle and defeat a powerful villain. However, the most powerful villain, Nine, ends up fighting both Deku and his childhood rival Bakugo at the same time. Both Deku and Bakugo use their most potent attacks, and as the audience thinks Nine is going to be defeated, he pulls out a hidden, secret ability and becomes even more powerful. Naturally, Deku and Bakugo must do the same in order to defeat their opponent. This is another classic shonen technique, in which the main character (or characters) are pushed to their absolute limit, forcing them to grow and increase in power. After Deku and Bakugo defeat Nine, the audience experiences the same effect as an upset victory in sports. The only difference is that almost everyone watching the movie is supporting the underdog, not the powerful villain.

The main reason the Shonen genre is so popular is because people of all ages are able to relate to it. For example, Marvel’s Avengers series is so popular because it follows the same kind of strategy Shonen anime does. The Avengers are just a collection of superheroes, who team up together to fight the powerful opponent, Thanos. In My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising, Deku and his classmates team up together and fight the powerful opponent Nine. This is why the movie was so successful. Just like the Avengers and other Shonen anime, My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising used techniques that older movies and TV shows have been using to entertain audiences for years. By Bill Friedell The seminal comic book series Watchmen, written by Alan Moore and drawn by Dave Gibbons, stood as a manifesto for the power of comic book storytelling by utilizing the most prevalent genre of comic books, the superhero genre. In doing so, Moore and Gibbons could explore contemporary fears of the 1980s, such as fear of nuclear war. In 2019, Damon Lindelof, along with a team of directors and writers delivered a sequel to Watchmen on HBO which shares the same name as the book. By utilizing the iconography and storytelling conventions of the comic, as well as building on top of them, Lindelof delivers a modern update to Watchmen that speaks to the modern landscape of 2019. HBO's Watchmen follows Angela Abar (Regina King), a police officer working under the alias Sister Night, as police officers in Tulsa Oklahoma wear masks and alter egos for safety reasons. The story is set into motion after the murder of Tulsa’s chief of police (Don Johnson). Angela, in her attempts to find out the truth over who murdered the chief of police, is pulled into a plot far bigger than she could have ever imagined. Like the comic book before it, Watchmen is structured with a mystery framing device that allows for deeper character studies of the characters engaged in the plot. The same goes for Lindelof’s Watchmen. While the mystery develops slowly in each episode, it is seldom the primary focus. Rather, the focus goes to its cast of characters, such as Angela Abar, Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias (Jeremy Irons), Looking Glass (Tim Blake Nelson), Lorrie Blake (Jean Smart), and many more. But the structural similarities don't stop there. The structures of many of the episodes also share similarities to structures of individual issues of the comics. The most glaring being the episode “A God Walks into Abar”, borrowing the nonlinear structure of issue four of the Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen, “Watchmaker”, as it replicates the nonlinearity of Dr. Manhattan’s perception of time. The purpose in both the comic and the TV show is to focus more on character than plot. Another aspect Lindeloff takes from the comic is the use of recurring symbols. While Lindelof and the other writers of the show do make use of these symbols, they find new spins on those symbols. There is a reference to the iconic smiley face button from the original comic twice in the first episode, “It’s Summer and We’re Running Out of Ice”. First, is a smiley face made of egg yolks. The second, when Captain Jud Crawford’s police badge gets blood dripped on it, a direct homage to the smiley face button of the Comedian, cementing the idea that Crawford is the Comedian of the TV show; the inciting incident that puts the story into motion. Another major recurring symbol from the comic is the use of clocks. Where a comic can visually show a clock, the show can use audio to indicate a clock. The ticking of a clock is referenced both in a message sent by the Seventh Kavalry in the video below and in the score composed by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. There is even a massive clock tower erected that plays a major role in the finale. The clock shares its meaning with the comic as it adds tension, especially through the common phrase, “tick-tock” that many characters say. The most common element of the clock motif between both the show and the comic is the counting down element. In the comic, it is counting down to nuclear destruction, where in the show, it points to a sort of racial reckoning that the Seventh Kavalry is attempting to enact due to a bill passed that pays reparations to minorities who have suffered from past injustices. Another component of Watchmen that is taken from the comic book is the roles and characteristics that the primary characters inhabit. The characters who inhabit the show have direct thematic ties to the characters of the original comic, those being Rorschach, Ozymandias, the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, Nite Owl, and Silk Spectre. Captain Jud Crawford inhabits the role of the Comedian served in the original comic and. His death acts as a catalyst for the story. Another character that fits into the role of the Comedian is Laurie Blake. In the original comic, she was the child of the original Silk Spectre and Comedian. She took up the mantle of her mother, but gave it up by the end of the original comics. In the TV show, she’s an FBI agent and is more callised than she was in the comic, resembling her father. Even her last name is a direct reference to her father, as Comedian’s real name is Edward Blake. Lindelof speaks about this on episode 1 of The Official Watchmen Podcast (2019). Both Looking Glass and Angela resemble Rorschach in that they are both heroes defined by trauma early in life. Angela also resembles the Silk Spectre in the way she is dealing with her legacy, as she is the granddaughter of the first vigilante in the world of Watchmen named Hooded Justice (Louis Gossett Jr). Lady Treiu (Hong Chau) fits into the role of Ozymandias, a hyper intelligent woman who is not only biologically related to Ozymandias, but also owns his company and is revealed to be the mastermind of the show, manipulating everyone, including the 7th Kavalry, towards her own ends. And even though these characters fit into these archetypes from the comic, these new characters are ultimately more than these archetypes. She also believes she is doing the right thing by enacting her plan, but in order to do what she wishes. Alternate history is another aspect of the Watchmen comic book series that he picks up and runs with. The biggest alternate history element that the TV show expands on involves Dr. Manhattan (Yahya Abdul Mateen II). As the only superpowered superhero in the world, he won the Vietnam War for the United States, making Vietnam a state. The show, like its comic book predecessor, explores the ramifications of superheroes in the real world. While the comic focuses on the Cold War and the potential of nuclear disaster, the show focuses on race and trauma, as stated in the third episode of The Official Watchmen Podcast (2019). Angela was raised in Vietnam, was born from two African Americans. In the first episode, she is seen wearing a Vietnamese outfit for a class presentation and in the pilot episode. Lindelof, on episode 1 of the Official Watchmen Podcast (2019), he compares Vietnam to Hawaii and how it is inspired by the colonial tendencies in America's past. We also see how politics have evolved since the original Watchmen, revealing that while superheroes are still illegal, cops are now allowed to wear masks to protect their identities due to a mass attack on the police in their own homes. The most thematically significant aspect of alternate history is in the exploration of the character Hooded Justice, the first masked vigilante in the Watchmen universe. In the comic, Hooded Justice is an enigma whose identity was never discovered. However, in the show, it is revealed that Hooded Justice was actually Angela’s grandfather, who hid his identity with a mask and face paint in order to keep his race a secret, as primarily shown in the episode, “This Extraordinary Being”, which showcases Angela learning about her grandfather by way of a drug called nostalgia which allows her to relive her grandfather’s memories. It also calls to mind the similarities they have, wearing face paint around their eyes (one black paint, the other white) as they also share similar trauma (losing parents at young ages), which is directly brought up by Craig Mazin, host of The Official Watchmen Podcast (2019) in episode 2.

HBO’s sequel series demonstrates a deep understanding of the source material from a construction standpoint while also not doing a repeat of the story of Watchmen. They take the story told in the original comic book series and found a way to not just build on top of the world that was established, but create their own path forward with their own twists and developments with both brand new characters and the characters from the original story in the comics. Even when rewatching episodes for the sake of this analysis, more layers that either point back to the comic or bits of foreshadowing were unearthed. By bringing in new characters, themes, and symbols to an established world and familiar archetypes, HBO’s Watchmen succeeds in creating a worthy follow up to the original comic. Works Cited HBO. “Episode 1.” The Official Watchmen Podcast, November 3, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiN5pR0nS80 HBO. “Episode 2.” The Official Watchmen Podcast, November 24, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G0RRDM_R8NY HBO. “Episode 3.” The Official Watchmen Podcast, December 15, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDe3iL052v0 Lindelof, Damon creator. Watchmen. HBO, 2019. Moore, Alan, and Dave Gibbons. Absolute Watchmen. DC Comics, 2011. By Daniel Sison Weathering With You, or Tenki No Ko, is a Japanese animated movie that has completely flown under the noses of the typical American viewers. This animated movie was directed by Makoto Shinkai, the man who created the animated film Your Name (2017), also known as, Kimi No Na, a movie that successfully entered highest grossing films in many countries other than the United States. In Japan, Your Name produced twenty-five billion dollars, which is just under Titanic and Frozen. The only other Japanese animated film that can compete with Makoto Shinkai’s works is the well known Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001). Weathering With You, or Tenki No Ko (which directly translates to “Weather’s Child”), is about a young, runaway high school student named Hodaka Morishima simply trying to live a normal life in Tokyo, Japan. Without any money, with no place to go, Hodaka eventually runs into a small-time publisher, who he begins to work and live with. One day, he sees a girl who had previously helped him surrounded by suspicious men. After he pulls her away from them, they slowly become friends, and she shows him her mysterious power - the ability to push the rain back and bring out the sun through prayer. Hodoka and the girl, Hina Amano, eventually start a business to clear the rain. This service immediately becomes popular because their city of Tokyo is being plagued by a never-ending chain of storms and downpour. The duo quickly realizes something is wrong when Hina begins to physically disappear. The story at first glance could fall under the category of fantasy, since the plot seems to revolve around a girl with super-powers. However, the movie actually uses the “fantasy element” to let realism shine. The movie focuses on the relationships of people, and how their daily lives can be affected. Although the concept of “bringing the sun out” is extremely simple, many complicated situations arise from simply possessing that power. The progression of the plot is also realistic - turning points do not happen faster than they need to, like many of the action movies showing today. Although the story is solid, it does not match in quality in comparison to the rest of the aspects of the film such as its art or sound. The plot was a little too simple and does not really stand out. Fortunately, the characters and the interaction between the characters is what made the movie so enjoyable. One example of character development can be found by observing Keisuke Suga. He is the forty-five year old writer who takes Hodaka into his own home because he sees his younger self in Hodaka. One day, when Hina Amano disappears, Hodaka does everything in his power to search for her, even going against the police. Keisuke sides with the police at first and tries to stop Hodaka. However, when Keisuke feels the blow of Hodaka’s passion, he remembers that he himself was once in Hodoka’s position, and eventually holds back the police to let Hodaka go. Hina Amano also receives her share of struggles. Her only mother passed away, leaving her and her brother to take care of the household. She had to work at various places in order to support what was left of her family. Then, after receiving the power to clear the skies, she had to come to terms with the fact that she would have to disappear forever and leave her brother behind as a result of possessing that ability. Unfortunately, the main character Hodaka does not undergo as much development as the other characters. Although he fights his own battles, he never really changes his ways or improves them. Instead, Hodaka is more of a character who causes change. He has his own goals, and with burning passion, he does not let anything stop him. The other characters catch onto his passion which allows them to change in their somewhat mediocre lives. The cinematography, along with the art and design of the movie is astounding. The character designs are pretty standard in the animated world, but what really stands out is the setting and atmosphere. It is almost difficult to believe that most of the art in the film has been hand-drawn by artists. Every time Hina Amano would clear the rain, each and every droplet would reverse its trajectory and begin to float towards the sky. Sound design is also a major contributor to the quality of the film. Paired with breathtaking scenes, the music and the sound quality can send chills down the viewer’s spine. The music from the movie was composed by Radwimps, a Japanese rock band. The band name Radwimps comes from the two English slang words “rad” and “wimps”. In other words, their name means “cool wimps”. They also created music for Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name, so he was already familiar with their style when he directed Weathering With You. There were two voice overs recorded for the film. Viewers are able to choose between “dubbed” or “subbed” showings. A dubbed anime means that the original Japanese voice acting has been replaced with English voice acting, while “subbed” anime means the film uses original Japanese voice actors accompanied by English subtitles. There are various pros and cons to each one. Viewers that watch the English version of the movie can fully experience the exquisite artistic ability of the creators. However, since the animation was originally created for Japanese voices, the “subbed” version fits much more naturally. Also, when translations go through, certain phrases and words come out different in English, since both languages are very different. A lot of times, watching the movie with a different set of voice overs can completely change it. Usually the English versions lack a lot of quality that many of the original Japanese versions have. However, in Weathering With You, the English version is done well. The voices match the characters and are well-edited. Overall, Weathering With You is an amazing animated film. The storyline was straightforward and realistic, while the characters were deep and complex. The art, animation, and music is extremely high in quality as well. However, like most Japanese films, this movie was overlooked by the general American audience. It may not be a mindblowing masterpiece like some of Makoto Shinkai’s other works, but it definitely is a hidden gem waiting to be discovered.

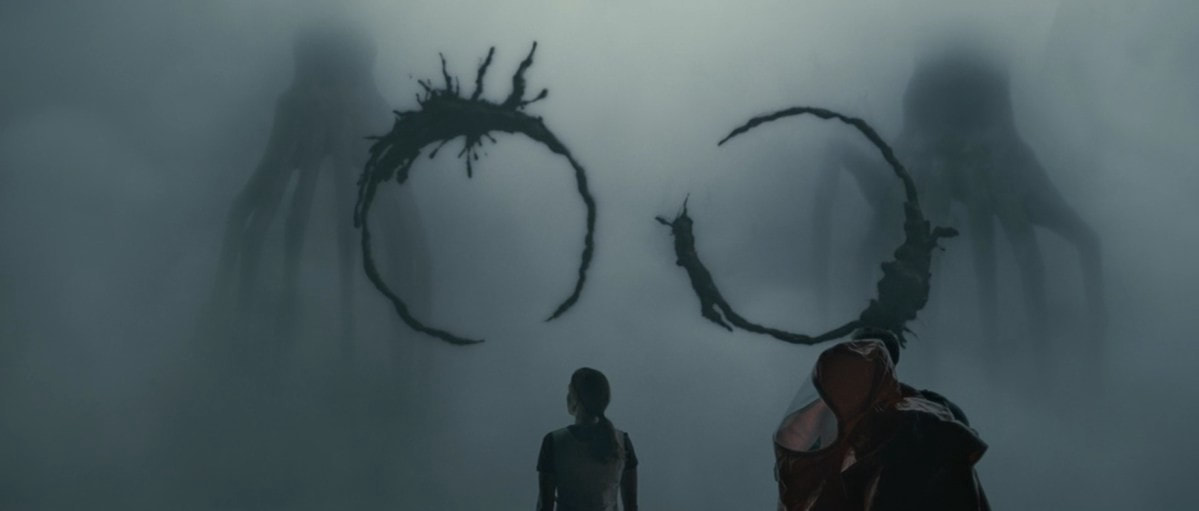

By Mason Leaver Dennis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) is a film which explores many topics and ideas. The film approaches the topics of extraterrestrial life, international communication, the loss of a child, and the concept of time with grace and subtlety. But the most intriguing topic that the film broaches is its conception of linguistics. Arrival explores this concept through the alien language of the heptapods, which teaches the main character how to think in new ways. By borrowing from philosophers like Kant, Nietzsche, and Sapir, Arrival presents an emergentist philosophy of linguistics, suggesting that the languages that we use change the construction of our cognition. Arrival’s story revolves around Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams), a linguistics professor who is called on to lead a team of scientists in learning an alien language. After 12 mysterious obelisks appeared in the sky, Banks and her team board one of these obelisks and discover it is a ship, and meet two aliens inside. These aliens are unlike any depiction of an alien previously seen in cinema. They are terrifying and strange; masses of dark flesh without clear form or distinction. These aliens are called heptapods, because of their seven legs. As Banks studies their language, she discovers that their sentences are written in a circle, and that they can be read starting anywhere in the circle. If we wrote our sentences that way, the phrase “I went to the store”, written circularly, could also be read as “Store. I went to the”, or any other combination. Banks becomes increasingly fascinated and engrossed in learning the language of the heptapods, until she eventually begins to even dream in their language. Eventually, she discovers the secret which the heptapods are trying to communicate with humans: that heptapods can see the future. Banks realizes that heptapods have a different conception of time than humans; one which is nonlinear. For heptapods, the future can be remembered just as easily as the past. When Banks realizes this, she also gains this ability, through the mastery of the heptapod language. The alien language reflects their circular conception of time, and learning this changes the way in which Banks conceptualizes time as well. The philosophy of the film is clear: the languages we speak can actually change the way that we think, including the way we think about time. But what sort of underlying beliefs does this philosophy have, and what are its implications? In order to properly understand the philosophy of language and of time which Arrival presents, we must first understand some underlying beliefs philosophers have formed about language and about time. One of the most famous philosophers of all time, Immanuel Kant, held that our knowledge of the future was knowledge which we could have without measuring it. This sort of knowledge is called “apriori” knowledge. Knowledge which we can only know after measuring it or proving it is called “aposteriori” knowledge. For example, our knowledge that 2+2=4 is apriori knowledge; just by thinking about it, we know it is true. However, the truth of something like “Oxygen’s atomic number is 8” is an example of aposteriori knowledge; we don’t know it just by thinking about it. Kant said that our knowledge of the future was apriori. We don’t need to measure or test the notion of the future to understand it. In even planning to test it, we would have already proven our understanding that there is a future. But in Arrival, the heptapod’s understanding of the future is fundamentally different from a human understanding of the future. For a heptapod, the future could be known apriori just as humans understand intuitively that there is a future. Arrival makes a bold claim: that our understanding of apriori knowledge is actually dependent on our language. In “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense '', Friedrich Nietzsche wrote about language, and what language is at a fundamental level. Nietzsche held that all language was, at its most basic level, a metaphor. He gives an example of a leaf. No two leaves are exactly the same. But by developing the concept of a leaf, we drop all of the differences between the two leaves. Words form metaphors by likening two things which are really quite different. By making these metaphors, “every concept comes into being by making equivalent that which is non-equivalent” (Nietzsche, 147). Over time, people forget that these metaphors are metaphors, and take them as literal truth, despite the fact that really, no two objects are the same. Nietzsche called this process of turning a metaphor into perceived literal truth as the process of conceptualization. When we perceive a particular object, we immediately conceptualize it into a word which does not capture the individual aspects of the object, but categorizes it with other things in the world. In the example of the leaf, we perceive this green thing on a tree, in all its individual intricacies, and immediately conceptualize it as “leaf”, and categorize it with all the other leaves we’ve seen. The interesting question which Arrival raises is in regards to the difference between the heptapod and human conceptualization of time. As Dr. Banks is learning the heptapod language, she has to understand time in an entirely different way. She finds the words and writing form extremely difficult to understand at first, and this makes sense. The heptapod language, including the circular way in which it is written, reflects a knowledge of both the future and the past. How are humans to understand the metaphors of the heptapod language when the words of the heptapod language conceptualize experiences which we’ve never had? How are we to understand another culture when even their written language serves as a metaphor for an experience which we can’t have? Arrival answers: by steeping ourselves in the culture and mindset of another, we can begin to understand experiences which we’ve never had. The final part of Arrival’s philosophy of language is actually addressed in the film. In one scene, Dr. Banks briefly refers to a concept called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Edward Sapir was a well known Emergentist philosopher of language. It is Emergentism’s “aim to explain the capacity for language in terms of non-linguistic human capacities: thinking, communicating, and interacting” (Stanford). Arrival holds to an emergentist approach to language: it’s concerned with how language affects our cognition. Emergentists, like Nietzsche, hold that language is a series of constructions (like the notion of time). According to Arrival, our human languages form a construction of time which is linear. Yet the heptapods hold an entirely different understanding of time. This raises the question: Which of these understandings is the proper one? Emergentists like Sapir hold to a concept called “cultural relativism”. Sapir expresses the notion of cultural relativism when he states “Language is primarily a cultural or social product and must be understood as such…” (Sapir 1929: 214). Cultural relativism, in the strict sense of the term, says that what is moral in one culture may be immoral in another culture, and vice versa. The Emergentist viewpoint of language expands this idea, saying that what is thinkable for you might depend on the language you know. Arrival answers the question of correct perception of time by answering the same way that Emergentists like Sapir would: Neither perception of time is correct or incorrect, but our languages determine what is thinkable or unthinkable for us. Nietzsche would agree with both Villeneuve and Sapir on this point. Nietzsche would say that the linear or the nonlinear view of time is arbitrary. It’s arbitrary which way you perceive the world, because there’s no criterion for that. We would need criterion for correct perception, which is nonexistent. How could we form such a judgment, about which perception of the world is correct? Instead, Nietzsche would say that by learning the metaphors of language used by the heptapods, Dr. Banks has learned new ways of conceptualizing the world, and in doing so, also discovered new ways of perceiving it. Works Cited Scholz, Barbara C., et al. “Philosophy of Linguistics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 1 Jan. 2015, plato.stanford.edu/entries/linguistics/. Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgement. A & D Publishing, 2018. Nietzsche, Friedrich, et al. The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011. For more from Cinemablography on Arrival, click here

|

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed