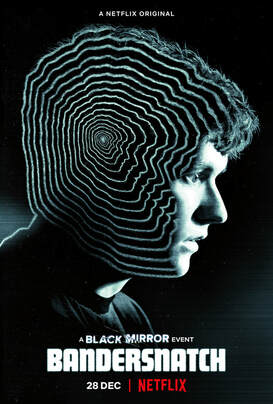

| Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) is an interactive film from the British science fiction series Black Mirror, and it is available exclusively on Netflix. The audience can now determine the character’s destiny through making various decisions for them. The plot is entirely customizable, meaning that there are multiple different endings to the film. Your experience will probably differ from someone else’s because your unique set of choices will lead to a specific outcome. Normally we would include a spoiler warning, but in this case there are many different endings that you may encounter, so reviews and opinions regarding this film are coming from specific experiences which you may not have yourself from viewing. In general, this is an entirely new way to consume content if you don’t consider it a video game, which it almost is. |

|

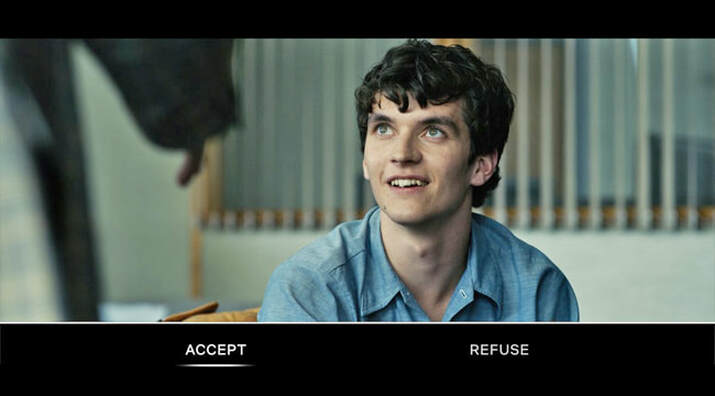

Let’s focus on analyzing this film in comparison to a video game, and what this different approach offers to the future of entertainment, and the film industry, in general. While Netflix has had this feature for some time, writer Charlie Brooker viewed it as an opportunity to make this season different. While initially seeming quite groundbreaking and revolutionary, this seems to be more of a proof of concept given that there are several dead ends in the script. It was disappointing to many viewers that their choice brought them back to the same point in the film, forcing them to make the “correct” choice which the filmmakers planned for. If this is true for every fork in the road that approaches, then what’s the point of involving the audience on this level at all? The actual premise of the film relates to the interactive concept, as the main character is a computer programmer from the 1980s who is coding a video game that allows you to do the same exact thing: make decisions for the character. He is inspired by a book titled "Bandersnatch" which also utilizes this concept. To what extent is this implemented? At first, just to get the viewer familiar with the interface, you are given the options between two different cereals which he can eat for breakfast, and then music tracks he can listen to on the bus. But after this, it comes down to more important decisions, such as a huge job offer for the main character, as seen in the image above. Choices like this are so significant that they have the potential to alter the entire plot. Why would you not choose the offer? Some viewers might just choose “refuse” to see the alternative, which ends up driving everything off of the script’s path. Sometimes, like mentioned before, you just end up going in a circle back to square one, which defeats the purpose of incorporating an external source. At one point, the character even acknowledges that there is something throwing him off of logical decisions, depending on what you choose. Netflix is even an option to communicate to him, which due to the time period, he doesn’t understand. Could this be the writers themselves recognizing that this feature has its limitations? Is this a game, or a film? To what extent should the audience intervene in a film in order to maintain its intended meaning? These questions are important to raise, because the acceptance of this feature may guide future films towards adapting it as well. Is this perhaps a way to draw towards Netflix as opposed to going to a theater? This is a much more personal experience, one that can not be replicated in a theater. Of course, as we all know, theaters offer certain immersive advantages that can not be achieved through a home entertainment system. However, this interactive element is something unique to a streaming service, and could not be a part of a theater due to the size of the audience. The decisions are meant to be made by a smaller group, or individuals. One can only imagine the complexity of the screenwriting process, considering the multiple paths that you can encounter in the plot. This also relates to the production since they had to film all of the different paths, which is probably the reasons why they opted for a single feature length episode this season instead of multiple. Besides just dwelling on the film’s flaws, let us admire its creativity and appreciate the addition effort that had to go into finessing multiple storylines into a single cohesive set of circumstances. Giving the audience more power is an interesting way to market a film. However, it is definitely refreshing to see more experimentation from a popular series which has very high expectations from viewers. It seems ironic for Black Mirror to be the first to implement this feature in this particular, because it already has a futuristic nature, and the pushes for innovation in the depicted stories. Only time will tell if this will actually catch on as a normal medium of films, or general entertainment as Netflix and home streaming becomes more popular. Written by: Dylan Delaney

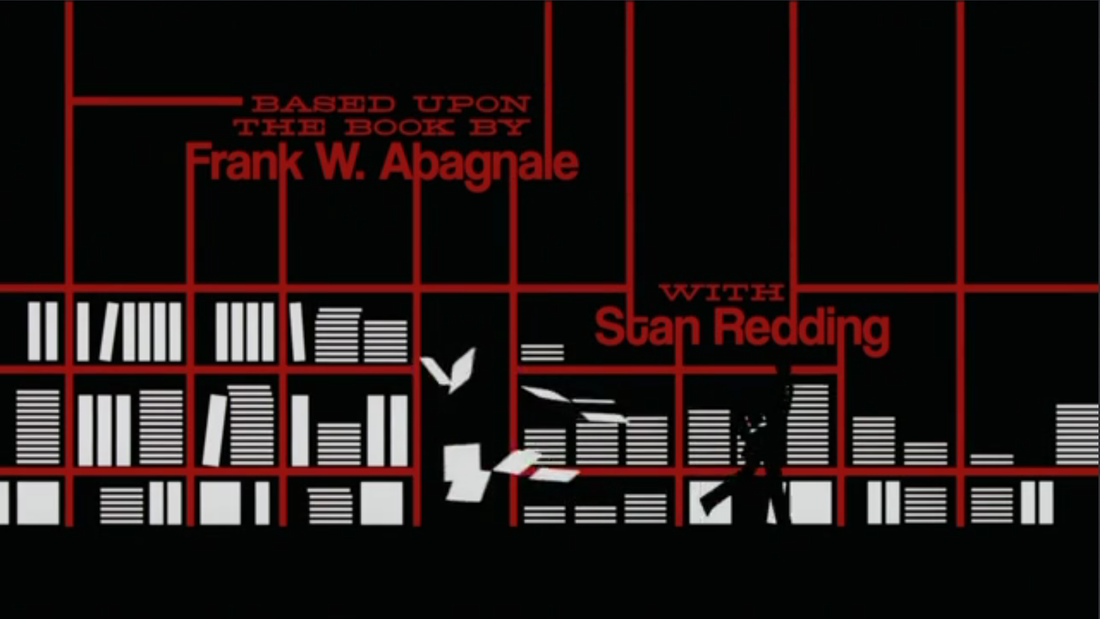

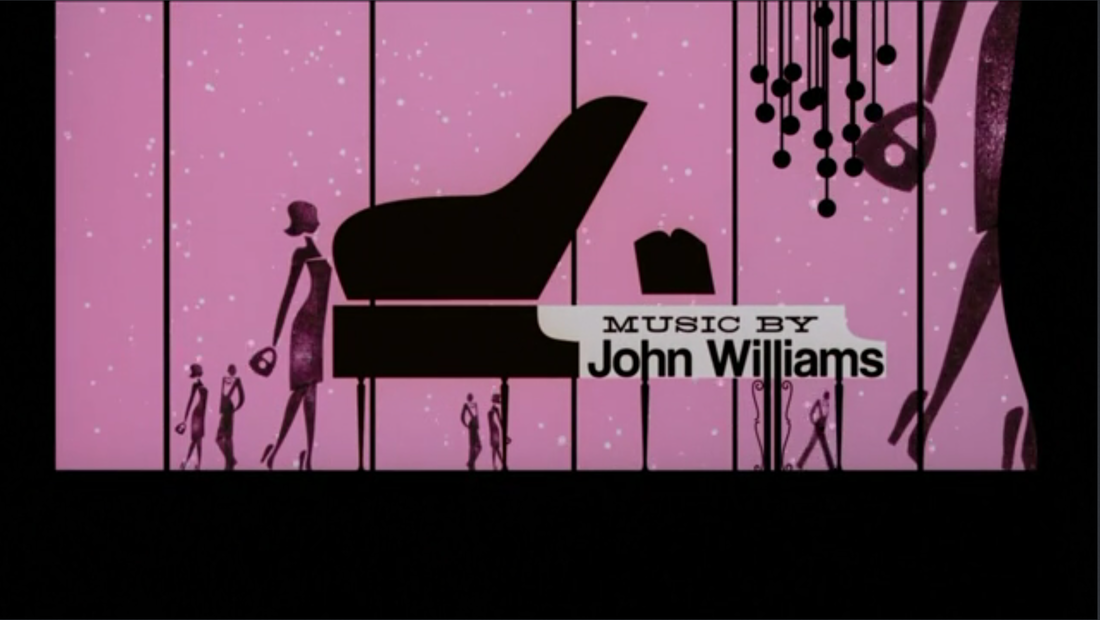

A whimsical jazz melody fills the air as a man scurries throughout the sequence, taking on different appearances as he is being stalked by a detective. The screen is filled with compelling typography and linear shapes extending throughout as the man tries to make his escape. In this title analysis we explore how the title sequence for Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me if You Can utilizes these details as a captivating homage to the legendary designer Saul Bass. The sequence begins with a silhouetted character moving throughout a blue background. As text for the credits shifts, airplanes begin to appear. The mysterious man watches intently at the pilots and stewardesses which emerge. He moves through a line on the screen, surfacing in a pilot uniform. As he does this, a huge silhouette of a detective is revealed as the space zooms out. The mysterious man is unknowingly watched by the detective as he moves throughout. As the main title appears the sequence transitions to a yellow resort background with a pool which the man swims through. As he reappears and passes by a large heel transforms into a doctor’s uniform. He meets a nurse and chats with her on an elevator until scurrying away as the detective gets closer. He switches to a business suit and is suddenly chased by the detective, moving throughout dynamic scenes of typewriters and archives of papers. He makes his final outfit transformation into a tuxedo as he attempts to escape from the pursuing detective. Him and the detective travel through a dark screen with lights sometimes appearing to shine on them, before entering into a scene of the night sky. As the detective finally begins to catch up with the man the screen fades to black and the film begins. The building blocks of Catch Me If You Can’s narrative are clearly laid out for unknowing viewers in the title sequence. This film is based on the true events of famous conman Frank Abagnale Jr.’s early life. After his father’s financial demise and parent’s divorce, Frank is compelled to run away from home. He quickly discovered that he his people skills gave him a natural ability to imitate personas of esteemed professional positions. He is successfully able to fool people into believing he is an airplane pilot, a doctor, and lawyer, while also gaining a knack at forging checks. This film is told through a series of flashbacks which envelop FBI detective Carl Hanratty’s pursuit to capture Frank. Designed by Oliver Kuntzel and Florence Deygas, hyperextended smooth lines drive the objects and typography of the title sequence. Lines move in and out of the screen, drawing audiences’ attention to the appearance and disappearance of the credits. In this same way the lines are used as entrances and exits for characters as they move throughout the screen. The characters also interact with the lines, hiding behind them, watching them, using them as a straw, a ladder, etc. These lines are always moving as if being chased in the same way Frank Abagnale is always on the run from Detective Hanratty. In order to “capture the spirit of Leonardo DiCaprio’s character” the designers chose to use an animation style which did not rely on the use of high-end technology. (artofthetitle) The characters were created in stamp form much like Abagnale’s use of stamps. The characters on screen are the designers original attempt, capturing the crudeness of his actions in the film. The playful score of this title sequence is a tune which captures the mischievous nature of Frank Abagnale Jr. and detective Hanratty’s sly pursuit after him. An original composition by John Williams, the instrumental gives off an old-fashioned jazz beat to the clever movement of text and objects on the screen. This score introduces a prominent leitmotif which appears several more times throughout crucial moments within the narrative of the film. Catch Me If You Can has a prominent focus on the sound track, utilizing this score (most noticeably Christmas music) to evoke certain emotions from the audience. It is in this same way that the nervousness that is stimulated by the title sequence is reformed to a quite different sentiment by the end of the film. The inspiration for the aesthetic for this sequence comes from the age in which its events take place. The goal of Kuntzel and Deygas’s was to give off a retro vibe and bring back audiences to the time frame of the film’s events (the 1960s). In doing this they found that there was no better way to do this than to implement a stylistic nod to Saul Bass’s minimalist design work. Looking at some of his posters for films such as Vertigo, The Man with the Golden Arm, and The Shining, there is a clear inspiration to the minimalist design of these pieces. This is especially evident in the character designs for the sequence. The title sequence for Catch Me If You Can utilizes fundamental minimalist designs which capture the audience through its musical tone and the short narrative depicted throughout it. The flashes of Saul Bass’s inspiration produce the 60’s vibe which encapsulates the film. Sometimes less is more and that is certainly the case with the notable design of this title sequence. Work Cited

https://www.artofthetitle.com/title/catch-me-if-you-can/ Written by Bill Friedell In a year where major franchises such as Star Wars and the Marvel Cinematic Universe are reaching end-points in some form or another, it is exciting to see the birth of something new and refreshing. Shazam! (David Sandberg, 2019), while harkening back to adventure films like The Goonies (Richard Donner, 1985), brings a refreshing point of view not seen in most superhero films: a genuine sense of wonder. Combining drama, heart, humor, and unapologetic visuals, Shazam! brings flavor all its own and tells a beautiful story about family. Shazam! follows Billy Batson (Djimon Hounsou), a foster child with a chip on his shoulder, who struggles with being adopted into a new family because he believes he can still find his birth mother. Meanwhile, Dr. Thaddeus Sivana (Mark Strong) searches for the power of the seven deadly sins of man. Unable to protect the world from the deadly sins, the wizard Shazam (Djimon Hounsou) must pass on his power to a champion before it is too late. Billy is chosen, becoming a fully adult superhero with strength, speed, and other amazing abilities and must stop Sivana and the seven deadly sins. The acting overall is really strong, especially from the child actors. Asher Angel as Billy Batson and Jack Dylan Grazer as Freddy Freeman (one of Billy’s new foster brothers) particularly stand out as they are given the most to do (Grazer in particular). Their friendship and bond which develops throughout the film is the heart and rock which the film is built upon. Freddy, a superhero fan, guides Billy in terms of discovering his abilities which also beginning to heal the chip on Billy’s shoulder. But they don’t shy away from the reality of Freddy’s handicap, allowing for amazing moments of drama. Asher too shines as he deals with finding his birth mother and interacts with his new foster family. He perfectly plays a teenager who has been through a lot but is still ultimately good. He believably interacts with everyone in the cast and perfectly shows the progression his character must make in order to grow. He’s not perfect (far from it), but nobody is, and he has the potential to become great. That is why he is chosen, despite not being an ideal pick for a superhero. Zachary Levi (playing Billy’s adult alter ego, inheriting the name Shazam) also delivers, bringing a child-like disposition while also developing alongside Asher as Billy, balancing perfectly between the two actors. While at first, it may appear that Levi is playing the part too comically, considering Billy’s initial coldness towards his foster family and place in life. However, Levi’s performance paradoxically captures a kid becoming an adult and regaining his childhood. By engaging with a child-like fantasy, he gains a sort of playfulness that any kid in his situation would have, playing with his powers in immature ways to learn more about them, such as putting them on Youtube. From a directorial standpoint, David F. Sandberg brings a balance of darkness and light that complement rather than weaken each other. Coming from the horror genre, he employs his horror toolbox with Dr. Sivana’s scenes, creating a threat with true weight because of the filmmaking, supporting the story being told. Sivana is the perfect foil for Billy, being the product of a family who didn’t support him and belittled him. He and Billy share a sense of loneliness as per their family situation. The difference is their response. Sandberg also handles the action well. While the scale is relatively small in comparison to other DC Universe movies, the action is shot coherently and finds inventive ways to use their powers and riff on tropes of superhero fights. One of the major set pieces of “action” is Billy rescuing a bus from falling from a bridge. While some might say these scarier Savanna scenes may be too much for younger audiences, the film is PG-13, so there is warning that this isn’t for little kids. And none of these scenes are gory, just intense imagery or savage attacks from the Seven Sins. While the film’s humor comes from playing with superhero tropes, such as learning about what superpowers you have and the fact that Billy and Freddy come from a world where Superman, Batman, Womder Woman, and the Justice League exist. While Deadpool (Tim Miller, 2016) does this, it takes a more wonderous approach, instead of the more mean-spirited attitude of Deadpool. While Deadpool is a mostly cynical film with a hidden heart underneath, Shazam! The overall cinematography and use of color are a lot more mature and overall better looking than most superhero films today. While there is a lot of grey winter weather, Sandberg and cinematographer Maxime Alexandre make excellent use of the color red, making it easier to follow Billy as himself and as an adult. Even the bright yellow lightning bolt logo makes tracking the character in action sequences at night a million times easier. Shazam! Is perhaps the most thematically well-handled film since Wonder Woman (Patty Jenkins, 2017). By focusing Billy’s arc around letting himself be open to family outside of those directly related to him, contrasted by Sivanna’s hate and dismissal of his own family, the film powerfully shows the joy and power in a family standing together in a truly unique way (I won’t divulge how, seeing as that contains spoilers). The foster parents and other foster kids: Freddy, Eugene (Ian Chen), Mary (Grace Fulton), Pedro (Jovan Armand), and Darla (Faithe Herman) are all unique from each other in appearance and personality, sharing great chemistry with each other, making it satisfying to see each other bond and accept Billy into their self-made family. Thanks to its excellent talent, from acting, directing, cinematography, writing, and production, Shazam! creates a refreshing blend of humor and heart. It doesn’t shy away from the darkness and drama in the story but finds balance in the humor and hope. It’s the kind of superhero film that can make even the oldest of moviegoers feel like a kid again.

Written By: Joseph Naguski Mirai is the latest film from Japanese film director and animator Mamoru Hosoda and his first to be nominated for an Oscar. The film presents to audiences a fantasy-driven tale of a young boy learning about his family through traveling within the past and the future. The film revolves around a four-year-old boy named Kun who loves trains and the struggles he and his family go through with the introduction of a new baby girl in their lives. On one day unexpected to Kun, his mother presents to him an unwanted new member of the family, his little sister Mirai. This new family member throws the house into chaos as Kun becomes filled with envy as the family’s attention shifts to his new baby sister. One day after throwing a tantrum Kun goes into his family’s garden and encounters a strange man claiming to be the prince of his house. The man whines about the attention he lost when Kun was born in the same way that Kun had been complaining about his sister. Kun realizes that the man is actually his dog. He ends up connecting with the dog and complains to his parents about the way they treat the dog. Throughout the film Kun encounters different versions of his family members in situations, including a version of his sister as a middle schooler from the future. These engagements help him learn more about those members and teaches him how to sympathize with them more. After getting lost at a train station in his fantasy world Kun must find a way back home or risk being lost forever. The character design of the film distinguishes the film. The way Kun is portrayed is exceptionally realistic to how many boys his age act in real life. His bratty nature is very relatable if you know any kids that age. In some circumstances he is shown to be too violent but he is a great protagonist to follow because of the way his character develops throughout the film. The rest of the family all have their own characteristics explored through Kun’s engagements with them in the fantasy world. This generates emotion from the audience as they invest in the characters. The animation coming from Hosoda is significant. Its combination of CGI and hand painted backgrounds bring the gorgeous world of Mirai to life. The film score is another proponent which makes its narrative so successful. From whimsical and adventurous melodies to somber and scary tunes the music throughout the movie really helps drive certain emotions into the audience. This is most prevalent in the scenes in which Kun travels from his home to another fantasy land. I watched the film dubbed in English as that was the only option available. I am usually not a fan of English voiceovers in foreign films because I feel like a certain aspect of the original emotion and meaning is lost. However, I think Mirai’s voice actors did a sufficient job of portraying the emotion of the scenes. Mirai’s heartwarming tale is a great film for both kids and parents alike. Its mixture of realism and fantasy does a good job of keeping viewers engaged in the story. This film can entertain a wide variety of audiences and should definitely be watched by fans of Japanese animated features.

By Bill Friedell It wasn’t until after my first viewing of the academy award winning Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018) that it dawned on me how few theatrical animated superhero films we have. While there have been some, such as The Incredibles (Brad Bird, 2004 ), The Lego Batman Movie (Chris McKay ,2017), and Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (Eric Radomski, Bruce Time, Kevin Altieri, Boyd Kirkland, Frank Paur, Dan Riba, 1993), most animated superhero films tend to be based on pre-established animated tv shows or franchises, and most tend to revolve around offshoots of Batman. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse showed audiences something that other animated superhero films could potentially employ better than live action films could: replicate the style of comic book storytelling. Not only by adapting this unique storytelling style does this film distinguish itself in the realm of animation, it also serves the very story it tells. Animation seems to be the perfect genre for incorporating comic book storytelling because like it too is an animation built on the foundation of illustration. The stylized visual elements of comics seem much more at home in a drawn environment because both art forms stem from illustration. To see an example of this style attempted in live action (with very different results) is Hulk (Ang Lee, 2003) and Scott Pilgrim vs the World (Edgar Wright, 2010). Hulk’s use of panel transitions comes off as distracting and overall doesn’t fit the aesthetic set out by the film. It distracts rather than enhances. Scott Pilgrim vs the World establishes a world in which the comic book and videogame aesthetics can coexist. Down below are some examples of how Hulk and Scott Pilgrim vs the World utilized this style.

One of the major techniques used to create this comic book feel in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse is the frame rate utilized by the animators. The film was shot on “twos.” This means that every other frame of character movements is used. This helps exaggerate the movements and allows actions to pop in the same way a comic book character does on a page. But it can also help sell the story beats in a really subtle way. In the sequence where Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) and Peter B. Parker (Jake Johnson) are running from armed scientists, Miles needs to learn how to web swing. Peter is a master of web swinging, so he is shot on a different frame rate, smoothly swinging. Miles, shot on twos, is out of sync with Peter. As he gets better, he and Peter match frame rates, showing Miles and Peter finally working well together and revealing both character’s progression without any dialogue. Perhaps the most prominent use of comic book storytelling techniques takes place when Miles goes through school after being bitten by a radioactive spider. For the most part, when following Miles, the comic book flourishes are restricted up until this point (with the exception of when he makes his graffiti art, which will be important later). Once he wakes up after being bitten, it acts as an onslaught. His thoughts are louder, written in thought boxes. His senses are enhanced, which is shown through beautiful multi-panel closeups of people talking about him. This use of the style displays his progression by the very placement of the comic book style storytelling. This is also seen in the mirrored scenes shown when he tries to swing between buildings. In the beginning of the film, he starts on a small building and falls, nearly dying, with a large “AHHHHH!” graphic following him. Later in the film, now believing in himself and sporting his own Spider-Man suit, he falls from upward (based on the camera position) and succeeds, with a “WHOOOO” graphic rising with him. These choices mean something in the greater context of the film by charting Mile’s growth and overall serving a purpose in the story. Nothing is superfluous. Another major part of the comic book storytelling aesthetic is the celebration of artistic diversity. Just as the various Spider heroes come from various backgrounds, genders, races, and universes, the art styles in which they are drawn are distinct and diverse from each other. Peni Parker (Kimiko Glenn) represents an anime/manga art style with exaggerated movements and poses. Spider-Man Noir (Nicolas Cage) is drawn in black and white, reflecting film noir. Spider-Ham (John Mulaney) resembles the slapstick simplicity of the Looney Tunes. Spider-Gwen (Hailee Steinfeld) has an elegance movement style and comes from a water colored world, reflecting her own hit comic book. By showcasing the various Spider-Men and Women in different art styles, it serves two purposes. One, it reflects Miles’ journey of self-discovery, seeing as he spray paints a Spider-Man costume to reflect his own style, mirroring his earlier graffiti art. Miles adopts a hip hop graffiti aesthetic, finally coming into his own as Spider-Man of his universe. But this diverse mixing pot of styles reflects the diverse art styles and stories that comic books, animation, and film can accomplish. Very few comic books in the market look alike, ranging from cartoony, to realistic, to impressionistic, to retro, and so much more. By each of these styles being put in a mixing pot, it celebrates the diversity and potential refreshment that new styles can bring. When you look at Spider-Man movies of the past, many share similar stories, particularly, the retelling of Spider-Man’s origin, which is a constant joke throughout the film. Mile’s story is an origin, sharing similar traits to the Spider-Man origin: being bitten by a radioactive spider, losing an uncle, making up for a past failure, etc. But the film tells the story in such a unique and artistic way that it feels like hearing the story for the very first time.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse is a love letter to comic book storytelling, superheroes, and Spider-Man. It represents the possibilities of looking at things through a different perspective. Superhero stories must allow for stylistic experimentation, just like how any other medium or genre must develop and grow in order to stay alive in the moviegoers mind and heart. By bringing in comic book storytelling that allows for diverse design, and characters that serves those characters and these stories, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse brilliantly marries animation and comic book storytelling to create a Spider-Man film unlike any other. And when there have already been so many Spider-Mans in live action and animated shows, that’s saying something. WORKS CITED WIRED, director. YouTube. YouTube, YouTube, 22 Mar. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-wUKu_V2Lk. |

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed