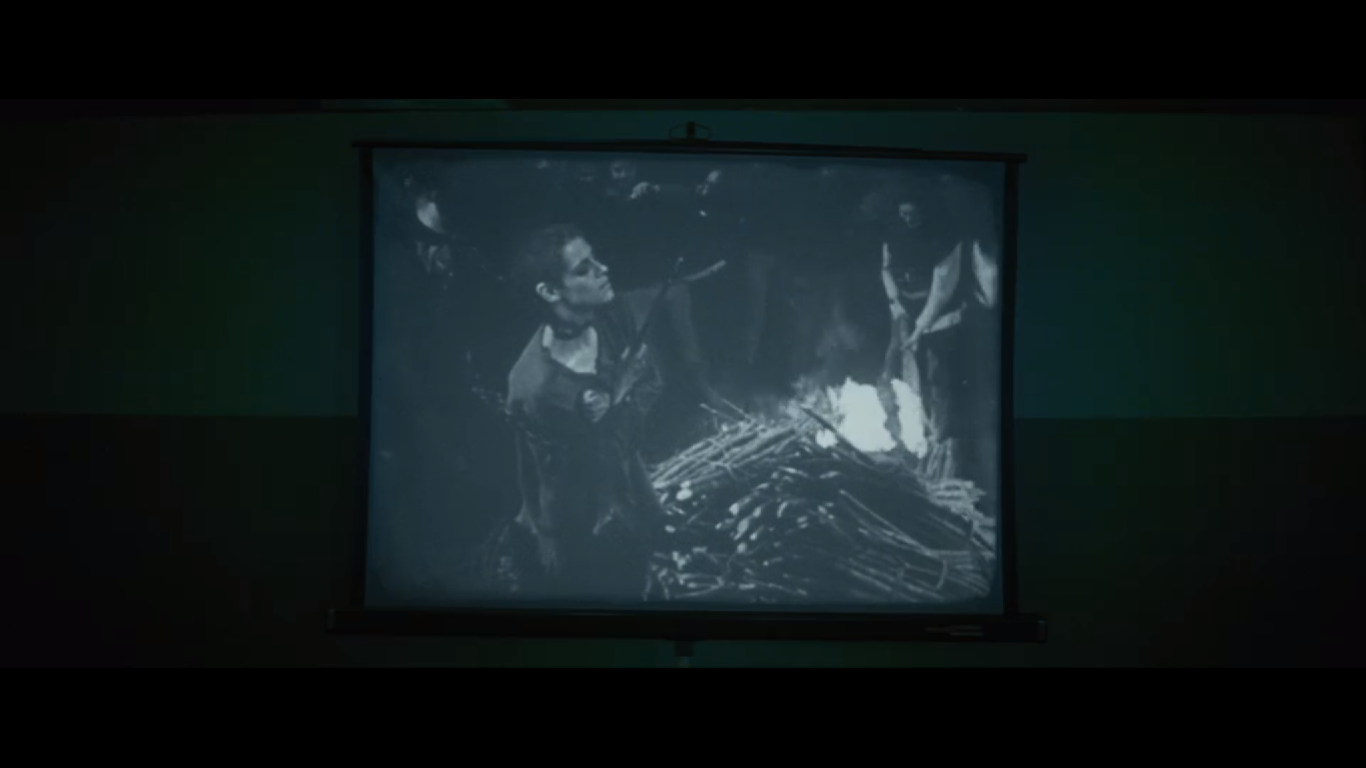

The film follows popular X-Men character, Logan, AKA “The Wolverine,” as he is invited to Japan to meet Yashida, a soldier he saved from the atomic bomb at Nagasaki. Yashida seeks to help Logan by offering him a way to die. Logan is gifted (cursed?) with the ability to regenerate at a rapid rate, allowing him to not only heal from fatal wounds in seconds, but to also live for hundreds of years without ageing. While Logan is young and healthy, Yashida is old and dying of cancer. He seeks to perform a sort of trade with Logan. If Logan is willing to give up his immortality to Yashida, Logan will finally be able to die and Yashida will be able to live.

While watching the film, I found myself immediately considering the state of Asian representation in film. Though the film contains many Asian characters and actors, we are still watching a white character fight his way through Japan. I’m not trying to say that The Wolverine is a problematic film, as I truly enjoy watching it and don’t feel like I am taking advantage of another culture by doing so, but it does tend to fit within the parameters of Orientalist cinema.

The Wolverine constantly interweaves the ancient and the futuristic. Logan visits Zōjō-ji for a funeral, where the yakuza show up to cause trouble. Logan fights them off, but what is interesting about the scene is the usage of modern firearms within an old religious site. It’s a jarring and strange sight to see, made stranger by the fact that an archer picks off gang members from the rooftop. As the battle progresses and Logan escapes with Yashida’s granddaughter, the target of the yakuza, he finds himself on a bullet train. The train serves as a symbol of the future, and Logan even comments on the fame of the train saying, “This is one of those bullet trains, right? So what do they do, like, 300 miles an hour?” When the yakuza board the train, Logan fights them again, but this time they are armed with knives or short swords rather than guns. It’s a reversal of the modern within the ancient, so now the ancient is within the modern.

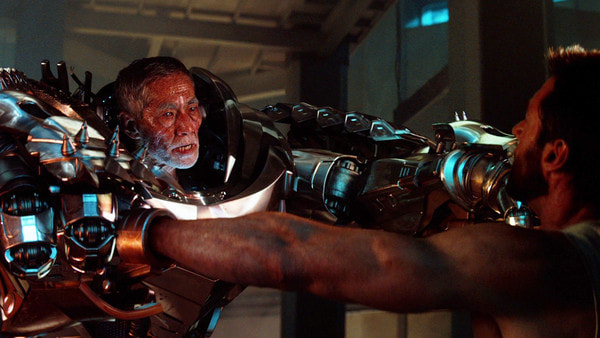

There are many other instances of this intermingling. In Yashida’s traditional style home, high-tech medical technology stands out like a sore thumb, yet because of the film’s aesthetic, we are not as jarred as Logan is. Towards the end of the film, Logan fights his way through an old village against ninja-like archers as he makes his way to a futuristic factory. In the factory he faces Yashida in a mech-suit designed to look like samurai armor. This is a sequence that truly captures the themes of old and young, as Yashida sits in a high-tech weapon made to look like ancient armor, and as he absorbs Logan’s regeneration power, Yashida’s old, withered face regenerates into the young face we know from the beginning of the film. The old becomes the new, and the new comes from the old. This is what the film is all about, as the characters, aesthetic, and even a subplot about Yashida’s inheritance all touch on this concept of continuity and growth.

This device is used in films such as The Outsider (Martin Zandvliet, 2018), about an American G.I. who joins the yakuza after release from a Japanese prison, or Lost in Translation (Sophia Coppola, 2003), about two Americans who meet in a Japanese hotel and fall in love due to their shared feelings of estrangement and loneliness. The Wolverine falls somewhere between these two films. The Outsider was met with much controversy, similarly to The Great Wall, and Lost in Translation achieved critical acclaim including an Academy Award for Best Writing, as well as a Best Actor, Best Director, and Best Picture nomination. While The Wolverine isn’t a masterpiece, it isn’t a disaster either, and it actually shows us some deep themes through the use of the ancient and the futuristic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed