Tim Burton’s style is quickly evident when one watches one of his films. Edward Scissorhands (Burton, 1990) and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Burton, 2007) are marked with his dreary and eccentric visual aesthetic. Burton also has actors he frequently collaborates with - such as Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter - who are normally given starring roles in his work. Danny Elfman, former lead singer of American New Wave band Oingo Boingo, composed the music of many of Burton’s films from Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (Burton, 1985) and onward. Most importantly, what makes his films so prolific are his themes - that focus on the darker aspects of humanity such as loneliness, revenge, and death. Taking a look at two of Burton’s animated works, we can see these core themes come out in full force. Animation gives Tim Burton full reign to explore loneliness, revenge, and death in interesting and imaginative new ways.

|

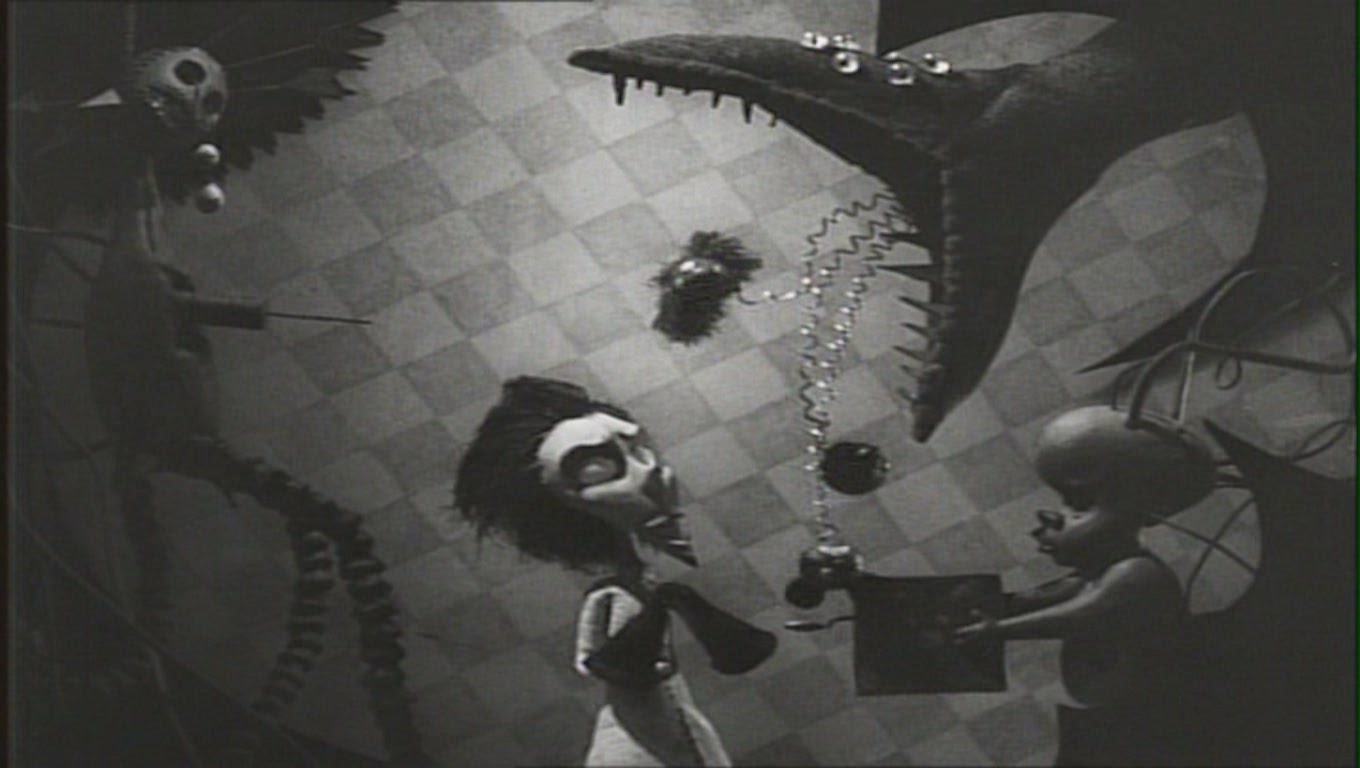

By Emmanuel Gundran Tim Burton’s style is quickly evident when one watches one of his films. Edward Scissorhands (Burton, 1990) and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Burton, 2007) are marked with his dreary and eccentric visual aesthetic. Burton also has actors he frequently collaborates with - such as Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter - who are normally given starring roles in his work. Danny Elfman, former lead singer of American New Wave band Oingo Boingo, composed the music of many of Burton’s films from Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (Burton, 1985) and onward. Most importantly, what makes his films so prolific are his themes - that focus on the darker aspects of humanity such as loneliness, revenge, and death. Taking a look at two of Burton’s animated works, we can see these core themes come out in full force. Animation gives Tim Burton full reign to explore loneliness, revenge, and death in interesting and imaginative new ways. His directorial debut, a short animated film called Vincent (Burton, 1982), demonstrates what makes Burton's films so distinct. The short tells the story of Vincent Malloy, a young boy who idolizes famous actor Vincent Price (much like Burton himself does). He idolizes him so much that he emulates Price’s on-screen characters, from Professor Henry Jarrod of House of Wax (DeToth, 1953) to Roderick Usher of The Fall of the House of Usher (Corman, 1960). His obsession results in him isolating himself from other kids his age. The boy’s daydreaming eventually upsets his mother when he digs up her flower bed, believing that he had buried his vengeful wife alive. The film ends on the boy's worst nightmares taking over his mind to the point that he believes that his fears have killed him. Diving deeper into these themes, the “Burton-ese” loner is one who is labeled an outsider for either their obsession or foreign characteristics. The former variety of loner is one that usually rejects society on their own twisted whim, whereas the latter variety faces rejection by the people of society who see the person as dangerous. Vincent Malloy initially fits into the former category, since he willingly shuts himself away from the outside world to focus on his passion. His mother encourages him to go outside and play, but he’s so overwhelmed by his imagination that he believes that he cannot leave the house because he is “possessed” by it. It is at this point that Vincent has become the loner now rejected by his society. His psychological state leads him to believe that his mother does not understand his plight in digging up his dead wife and is banishing him to an eternal prison in a high tower. This is very similar to the type of loner seen in many of Burton’s other characters like the Penguin from Batman Returns (1992) and Edward Scissorhands from the 1990 film of the same name. Both of these characters are outcasts due to society rejecting them for their physical deformities. Burton’s Corpse Bride (2007) continues with these themes, especially toying with people’s expectations of living and dead and exacting revenge from beyond the grave. Victor Van Dort (Johnny Depp), a shy, poor Victorian man betrothed to marry the equally as shy yet rich Victoria Everglot (Emily Watson), is inadvertently roped into marrying Emily (Helena Bonham Carter), a corpse bride. While Emily was alive, she wanted to marry a man named Barkis Bittern (Richard E. Grant), but he killed her under the cover of darkness in the forests. Until the time when Emily would find her love in Victor Van Dort, she lived underground in the realm known as the Underworld. Though the place is inhabited by undead creatures and monsters, the Underworld is an optimistic, colorful contrast to the land of the living, which is a classic picture of the bleak world of Victorian England. Death is like a release from the anxiety and cynicism of living and allows the spirits of the dead to party for the rest of their after-lives. One elderly skeleton even says to Victor, as he is about to leave the Underworld to return to the land of the living, that “people are dying to get down here.” It is also evident that the monsters of the world below are generally more friendly and inviting to Victor than the living people of the surface world, who cheat and murder to get what they want out of others. A humorous detail about the Underworld is that part of the culture of their world mirrors a more modern setting, with a skeleton singing 1920’s-style jazz at an undead bar. It goes to show the Underworld is a place not only beyond the bounds of the physical body but also the restrictions of time and economic poverty; it is an oasis where souls can go to rest. Finally, there is the matter of fulfilling personal desires beyond the grave, such as revenge or true love, that is shown in Corpse Bride (Burton, 2007). Throughout the film, Emily hopes that Victor is her one true love who will fulfill her after her death at her former lover’s own hands. However, by the end, her true fulfillment comes from her not only banishing Mr. Bittern to the Underworld for her death and finally getting her revenge, she is also satisfied seeing Victor marrying the woman who he truly loves. The film indulges in the idea of people’s souls returning to the land of the living to complete their work and find peace. When Emily’s purpose is fulfilled, her undead body transforms into a host of beautiful butterflies and ascends to a higher plane known as “The Land of the Reborn.” Tim Burton’s animation truly captures his distinctive style, not only in an audio-visual sense, but also in the way that he explores the darker aspects of life and how people relate to their environments.

Toula (Nia Vardalos) and Ian (John Corbett) on their wedding day (My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Zwick, 2002)

by Megan Hess

If, it is true, as Jane Austen once said in the opening words of Pride and Prejudice, that “it is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife” (Austen 1) then it is also true that a single women in possession of a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wedding. With at least 2.5 million weddings each year, generating over 50 billion dollars of revenue, according to Wikipedia, the wedding industry is one of the most lucrative and tradition-rich pieces of American culture, but it is also one of the most normative. The “wedding movie,” an important subgenre of the romance\romantic comedy genres reflects this normativity. Using the framework of Audre Lorde’s “mythical norm,” I will look at examples and counterexamples of normativity in the American wedding movie of the 2000s.

The idea of the “mythical norm” comes from the African-American feminist writer\scholar Audre Lorde. She first introduced it in a paper she presented at Amherst College in April 1980, entitled “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” According to Lorde, “Somewhere, on the edge of consciousness, there is what I call a mythical norm, which each one of us within our hearts knows "that is not me." In America, this norm is usually defined as white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financially secure. It is with this mythical norm that the trappings of power reside within this society” (2). Lorde’s “mythical norm” deals with the presence and absence of oppression and privilege – the assumption that those whose bodies and social positions adhere closer to the “mythical norm” will be better insulated from certain hardships of life. For the purposes of this article, I will focus more on the privilege aspect of the “mythical norm” than oppression. The typical protagonist of the American wedding movie fits the mythical norm. She is a young, white, woman with a low body fat percentage and high salary, marrying a man. Let’s look at an example: Jane, Kathrine Heigl’s character from 27 Dresses (Fletcher, 2008)

With the castoffs from 27 weddings in her closet, Jane exemplifies “always a bridesmaid, never a bride” – but she still has the look of the wedding-movie bride she becomes. She works as a personal assistant to a magazine editor, which might cause the viewer to assume she doesn’t make much money, but her spacious, well-lit apartment says otherwise. Even though the dresses in this scene range from goofy to hideous, she still looks pretty – an intentional choice. The wedding movie protagonist is always pretty in that bland, basic-white-girl way. If she doesn’t always start out with that look, she ends up with it. One example is Toula Portokalos (Nia Vardalos) the protagonist of My Big Fat Greek Wedding and its sequel. At the beginning of the film, she does not feel very happy or excited about her life, and her style reflects that sense of drab hopelessness. The movie codes her as “unattractive” (and, by association, unlovable) through monotone, full-coverage clothing, minimally styled hair, no visible makeup, and glasses.

Toula (Nia Vardalos) pre-makeover (My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Zwick, 2002)

Hence, it is no coincidence that, once she invests more time into her personal style, that she finally finds a man worth marrying.

Toula post-makeover (My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Zwick, 2002)

The makeover trope is almost omnipresent in movies marketed to women, and the wedding movie is not exempt. While Toula is different from other wedding movie protagonists because she actually has a distinctive ethnic background, it’s telling that she has to transform her physical appearance to match theirs to find love.

The former examples have established the trend of the mythical norm’s presence in the American wedding movie. One question to ask is: why is this so prevalent? Granted, these films were made in a time with less overt awareness of race, class, gender, and sexuality issues, but, even then, women and men who do not fit the mythical norm were falling in love and getting married in the public eye. Why is the only wedding story worth representing belong only to the slim, white, middle-class female? Part of it has to do with marketing. The women of the mythical norm are the target audience of these movies, and, if they can see themselves in the narrative, they will (hopefully) be more successful at the box office. This worked with 27 Dresses, which made back almost all of its $30 thousand budget in its opening weekend, and doubled that figure by the end of its run in theaters (IMDB). When films with the mythical norm as a driving force do well, it only perpetuates the trope. White male producers think this is what women want because this is what society has told them women want. Women working in the mainstream movie industry often don’t correct them because of the power imbalance, the social expectation that it is what they should want, and the money. From a socio-cultural angle, it is often the most privileged in society – those who totally embody Lorde’s mythical norm – who create culture, especially mass culture. The tradition of men making “women’s films” could be another article entirely. They are reflecting what they know and what they have seen around them: whiteness, and the women of the mythical norm. Even when women are involved in writing, producing, or directing a film, she usually works with men in the other big production roles. (27 Dresses breaks tradition here, with a female scriptwriter and a female director.) However, often as culture changes, popular culture changes with it. Bridesmaids (Feig, 2011) serves as a counterexample to the mythically normative films mentioned above. While Annie (Kristen Wiig), the protagonist is very much a product of the mythical norm, she does not also get to play the bride role. That goes to her best friend, Lillian (Maya Rudolph).

Lillian (Maya Rudolph, second from right) goes dress shopping with her bridesmaids (Bridesmaids, Feig, 2011)

In a typical wedding movie, any of the other bridesmaids (except Melissa McCarthy, unless this were a “makeover” wedding movie like My Big Fat Greek Wedding) would be the protagonist, and Lillian would be the token minority bridesmaid. Bridesmaids inverts the trope by putting Lillian in the coveted role of bride-to-be. They make it seem normal because it is normal. Bridesmaids’ move is not completely groundbreaking – Lillian still fits into many aspects of the mythical norm, even if she cannot totally claim whiteness – but it is one step towards increasing diversity in the American wedding movie.

Cultural scholars can and should critique wedding movies for their role in perpetuating classicism, heteronormativity, and white, thin, and “pretty” privilege, along with feeding women’s drive to have the Pinterest-perfect, cake-topper, wedding. However, lambasting the genre will not make it go away. Weddings are significant cultural and personal events, and should not be excluded from onscreen representation. I believe wedding movies will become even more enjoyable when they reflect our multicultural, diverse, world instead of just the “single white female” experience.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice New York: Modern Library, 1995. Print “Box Office\Business for 27 Dresses” IMD, n.d. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0988595/business?ref_=tt_dt_bus Accessed 11\5\17 Lorde, Audre. “Age, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference” https://www.colorado.edu/odece/sites/default/files/attached-files/rba09-sb4converted_8.pdf Accessed 11\5\17 “Wedding Industry in the United States” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wedding_industry_in_the_United_States Accessed 11\5\17 Kumail (Kumail Nanjiani, right) and the Gardeners (Holly Hunter, left and Ray Romano, center) hear the doctor’s news (The Big Sick, Showalter, 2017) by Megan Hess The Big Sick (Showalter, 2017) is boy-meets-girl with a twist – one that involves major medical problems. From the name, it sounds like it might be a film about cancer, but it’s actually closer to If I Stay (Cutler, 2014) than The Fault in Our Stars (Boone, 2014). The marketing campaigns I saw over the summer when this movie first premiered in theaters used humor as its main selling point – so I experienced something very close to a bait and switch when actually watching the movie. (I do admit this may be avoided if one does more thorough research beforehand, but also advocate going in with little prior knowledge, as it makes the plot twists more impactful.) This is, in no way, a bad thing. I loved the true-to-life way The Big Sick balances comedy and tragedy, happiness and hardship. It has an advantage over other narratives in that it’s based on true events, so perhaps that was what made it easier to achieve. Kumail (as himself) and Emily (Zoe Kazan) at a party (The Big Sick, Showalter, 2017) If I had to sum up the movie using a common axiom, it would be “life turns on a dime.” Kumail Nanjiani (playing himself) isn’t looking for a relationship on the night he first meets Emily Gardener (Zoe Kazan). The two have a two-part meet-cute that ends in a one-night stand. Although they say it will be a one-time thing, they keep coming back to each other. To use one of my favorite book quotes of all time (from John Green’s The Fault In Our Stars) they “fell in love the way you fall asleep: slowly, and then all at once” (Green 125). But Kumail’s inability to be fully honest – with Emily, his parents, and himself – interferes with the future of their relationship. When Emily has a sudden and baffling health crisis, he comes back into her life… under duress (at first). Now comes the best part of the movie: Emily’s parents. The Big Sick’s casting director did an incredible job filling these roles. Even though Terry and Beth Gardner (Ray Romano and Holly Hunter) don’t appear actively in love at first, they have incredible chemistry. The comedic moments with their characters are funnier than any of the stand-up comedy performed in the film – including Terry’s “dad joke.” Unfortunately, this near-perfect paring dims the other performances a little. On that note, I also wish Aidy Bryant’s character had a bigger role, or that we at least got to see more of her stand-up, and less of Kumail’s man-child roommate’s (Kurt Braunohler) stupid jokes. (He may look like a young Jim Gaffigan, but he has none of his comedic ingenuity or timing). Kumail's friends and fellow stand-up comics, Mary (Aidy Bryant) and CJ (Bo Burnham) attend a performance of his one-man show (The Big Sick, Showalter, 2017) While The Big Sick was marketed as a romantic comedy, to me, it’s a “gray comedy:” not dark enough to get the black-comedy label, but not a lighthearted, rapid-fire jokes film, either. It’s a comedy for people who don’t think they like comedies – meaning, a lot less raunchy than other movies Judd Apatow has produced, and with smarter jokes. What’s truly compelling about The Big Sick is how it plays with the niche and the familiar. Most audiences cannot relate to Kumail’s specific experiences of being a Pakistani stand-up comic in Chicago, but everyone has watched someone they care about suffer, bombed a big presentation, or hidden something from their parents. Overall, Kumail functions as an everyman whose relatability makes him an effective protagonist, driving the film forward and keeping the viewer engaged. If you want a film that makes you think (and makes you thankful), don’t miss out on The Big Sick. Works Cited

Green, John. The Fault in Our Stars. New York: Penguin, 2012. By Jack Waterman Let’s face it: maturing is something that everything and everybody must go through. Movie genres are no exception. When they are young, they are full of life and excitement; filmmakers attempt to push the envelope of genres in any way they can. But sooner or later, the genres grow up. It is not uncommon for there to be a single movie that rewrites the genre and forces the audience to rethink what they know about it. For Westerns, there is Unforgiven (Eastwood, 1992). For war films, there is Saving Private Ryan (Spielberg, 1998). And for horror movies, I believe, there is The Babadook (Kent, 2014). If you distill the structure of The Babadook into basic horror movie terminology, you end up with a generic “main characters get stalked by a terrifying monster”. And judging by the lukewarm reviews of the film from casual moviegoers, this is pretty much what most people were expecting. But the actual execution of this premise is so drastically different from other horror movies that The Babadook was ultimately transformed into one of the first major “anti-horror” movies. Essentially, it is a film in which the traditional logic of horror movies is taken to its natural conclusion. What do I mean by this? In my intro, I brought up Unforgiven and Saving Private Ryan. In both of these movies, the traditional cornerstones of their respective genres were stripped away and the cold, horrific reality of the main characters’ situations was revealed. The self-assured, morally superior, invincible heroes of old were revealed to be ordinary, flawed people, or worse, vicious and unscrupulous monsters. The real-life consequences of people’s actions were brought into focus, and the main characters were forced to confront them. Unforgiven is a gritty reinterpretation of the western archtypes. In the case of The Babadook, this expresses itself a little bit differently, probably because horror movies aren’t particularly renowned for their strong characters. They typically rely on sheer spectacle to get by, which has led some to compare horror movies to pornography. I admit this isn’t totally unreasonable: audiences go to a movie theater, watch characters die in the most explicit ways imaginable, and then go home. What horror films don’t show are the messy emotional aftermaths of such brutal slayings. When someone’s friends, family, or lovers are murdered in real life, it has lasting psychological damage on them. The person might develop PTSD, depression, and even end up committing suicide. This is the essence what The Babadook is all about and what I mean when I say it’s an “anti-horror” movie. There are plenty of ways The Babadook deconstructs the basic building blocks of horror movies, though it’s done in a different way than say, Scream (Craven, 1996) does. Rather than putting the characters into a generic horror movie scenario and having them be self-aware of it, The Babadook plays everything completely straight. There is an almost total lack of humor or comic relief, which is quite the rarity for a movie that is attempting to dismantle the various tropes in its respective genre. Going off the logic described in my previous analysis of Housebound (Johnstone, 2014), The Babadook could technically be considered a horror parody, albeit one that isn’t humorous. Amelia eventually confronts and defeats the Babadook in a rather unconventional manner. And what are some of these tropes The Babadook dismantles? For one thing, it redefines the nature of a horror movie’s “precursor event”. Though it’s not generally brought up in conversations about horror as a movie genre, one thing I have personally noticed in a great many scary movies is that there is almost always some sort of major happening that sets the rest of the movie in motion. In A Nightmare on Elm Street (Craven, 1984), it’s the burning of Freddy Krueger. In The Thing (Carpenter, 1982), it’s the alien spacecraft crash landing into the Antarctic. And in The Shining (Kubrick, 1980), it’s Charles Grady’s murder of his family. In these movies, the precursor events are directly tied to the plot, and the monster/killer arises as a result of the events that transpire. In The Babadook, however, the precursor event itself is the monster. Or at least, Amelia’s depression caused by her husband’s death is. This is what gave me pause and brought the film to a whole other level for me. Ultimately, The Babadook is an incredible meta-horror movie that doesn’t feel like meta-horror movie, and that in and of itself is quite an accomplishment.

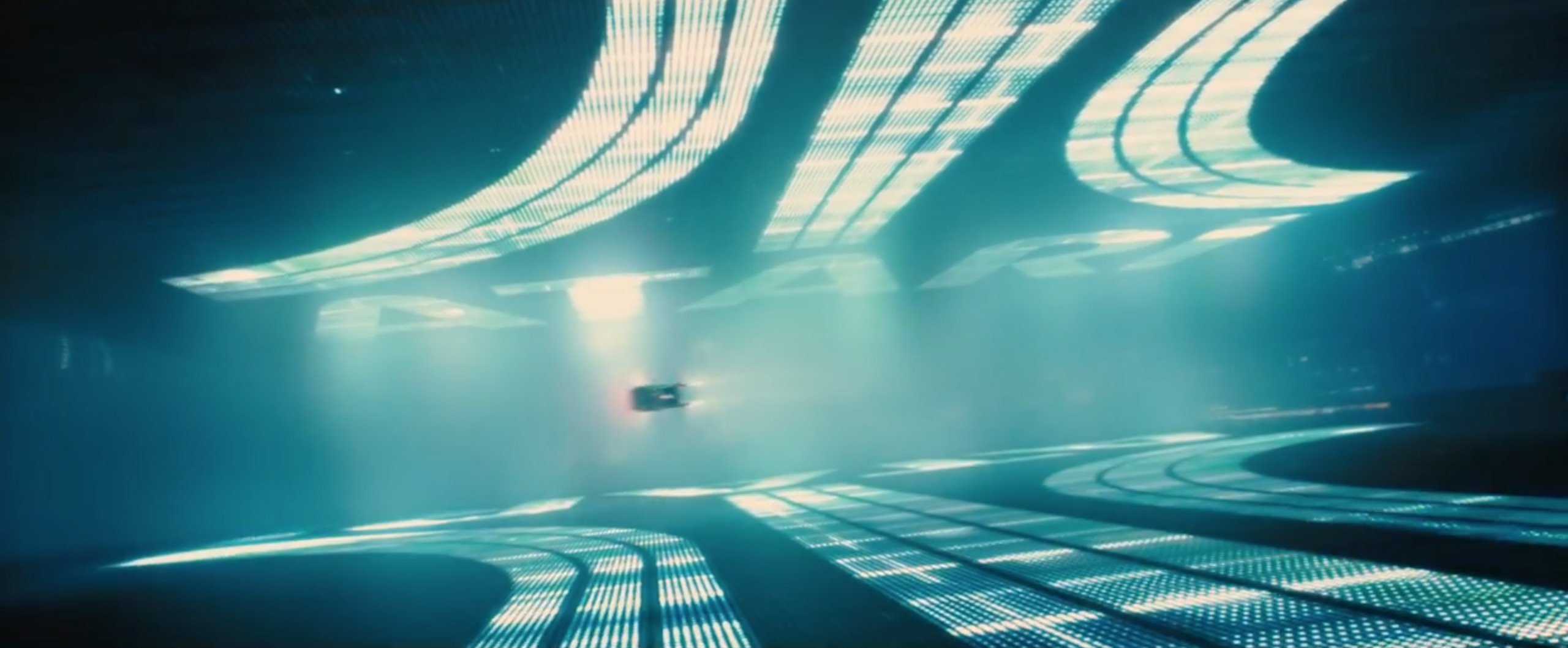

By Nathan Simms By all accounts, Blade Runner 2049 (Villeneuve, 2017) was a box office bomb. With an estimated budget of $150 million, the film needed to make significant returns to break even, which it failed to do. However, do not let its financial success be the deciding factor in whether or not you see it. Despite its poor performance, Blade Runner 2049 is a visually stunning and philosophically poignant sequel to a film that never needed one. The original Blade Runner (Scott, 1982) helped to usher in and define Neo-Noir in American cinema. Stuffed with smoke and smog, the Los Angeles of 2019 is a dark and mysterious place, where Blade Runner Rick Deckard hunts humanoid robots known as Replicants. 30 years later, Blade Runner and Replicant K-played wonderfully by Ryan Gosling-hunts even more advanced Replicants in a future that is considerably more bleak. The visuals of 2049 match wonderfully with the cityscape and Neo-Noir feel of the original. Known for his prior collaborations with Denis Villeneuve, Cinematographer Roger Deakins absolutely builds upon the visual language of the first film and evolves it into something that simply must be seen to be understood. 2049 features a number of wide, sweeping shots which show the world in its gritty glory. As human pollution has worsened, the smoke and fog of the original are exacerbated to a point of figurative suffocation. A number of times, K leaves the city and travels through an agrarian portion of California to work on his case. In these scenes, we get our largest glimpse into the effect of pollution outside of an urban environment. And it looks very much the same. The permanent night and neon light of the city are absent in these scenes, but the sun-bleached vistas that are offered instead are not much more uplifting. Ultimately, the cinematography of this film is an experience unto itself. It is evident that Deakins and Villeneuve but an extraordinary amount of thought into each shot and sequence. Each and every scene features something eye catching, from the overall composition to the miniscule details featured in the mise-en-scene.

The story of Blade Runner 2049 is also artfully crafted. The questions posited in the original, such as “what makes us human?”, are addressed again in the sequel and are significantly expanded upon. At the same time, the ambiguity and general lack of closure from Blade Runner continue into 2049, leaving the audience with a feeling that they cannot really put a finger on. Blade Runner 2049 is a movie that simply must be experienced to be understood. It is one of the most raw and visceral films that I have seen in recent memory, and its visuals and soundscape stick out in my mind. 2049 is cinematographically gorgeous film and a surprisingly good sequel to an 80’s movie, a definite departure from recent pulpy 80’s remakes. Despite its financial failure, maybe 2049 will find its success in the same manner that the box-office bomb Blade Runner did, finding its identity as a cult-classic. By Jack Waterman I have a bit of a confession to make: I, a self-proclaimed cinephile, don’t really like movie theaters that much. I don’t like the astronomical prices, I don’t like stepping over spilled drinks, I don’t like the noisy people in the audience, and I don’t like the 20 minute long previews. Why do I bring this up? Because I actually saw The Witch in a clean, empty movie theater, and it was legitimately one of the greatest viewing experiences of my life. The showing was largely free of distractions, and I was able to focus much more intently on the film’s minute details. And there were a lot of minute details. The Witch is a 2015 horror film directed by Robert Eggers, who has a relatively sparse list of directing credits, and primarily does work in production design and costume design. The film centers around a family of Puritans during the early 17th century, excommunicated from their church and living in a remote part of the New England wilderness. After their newborn baby disappears, strange happenings start occurring around their homestead, and the family begins to spiral into paranoia and madness. Anya Taylor-Joy as Thomasin in The Witch As is all too common with critically acclaimed, low-budget, independent horror films, The Witch was tragically overlooked by most of the general public, and the few casual filmgoers that did see it gave it lukewarm reviews. And I openly admit that this is not a movie for everyone. It is practically the dictionary definition of a slow-burn horror movie, and those expecting a ceaseless onslaught of jump scares and crimson showers of viscera will be sorely disappointed. Though it is only about an hour and a half, the film never once felt rushed or bloated, and in fact feels quite a bit longer than its running time. You can feel the family tearing itself apart minute by minute, and the sense of despair and dread that pervades the movie is crushing. The tone of The Witch is further enhanced by the simple, yet highly effective camera work. Admittedly, you won’t find too many surprises; the camera generally remains stationary, and there is little in here that will truly wow you. Nevertheless, the cinematography has this sinister, creeping feeling that bodes very well with the film’s subject material. As Drew McWeeny from HITFIX observes, “It feels like we’re watching something we should not be seeing.” The color palette (or lack thereof) also contributes to the film’s atmosphere: bitter, bleak, muted hues make it seem as though the life has been sapped from the landscape, highlighting the tormented family’s hopeless situation. Harvey Scrimshaw as Caleb in The Witch The acting and characters are where this movie truly shines. All of the actors, even the youngest children, do a superb job. Everyone speaks in a flowery, times-accurate King James-y lilt, which works wonders in regards to immersion. Though, if someone were to watch The Witch without knowing this beforehand, it would probably make the movie hard to follow. As a matter of fact, this was far and away the biggest complaint I heard about the movie. Still, for those of us who are dead set on historical accuracy, you will be greatly satisfied. But to be honest, even if there were no accents, the characters would still be fascinating. There’s a huge emphasis on the role of religion for early European settlers, and the constant struggle between religious life and the well-being of the family makes for a captivating and suspenseful story.

Is there anything I didn’t like about this movie? From purely objective, critical perspective, there’s very little in The Witch to find fault with. I do think that I should give a fair word of warning, however: though this movie doesn’t have a whole lot of onscreen violence, is still very unsettling and disturbing in its implications. An example would be when the movie reveals the ultimate fate of the family’s missing baby. I should also mention that this movie is exactly as scary as you want to be. And no, that isn’t meant to knock the film’s scariness overall. This just means that if you’re willing to use your imagination, really invest yourself into the characters, and analyze the fine details, The Witch can become the scariest movie you’ve ever seen. What you put into the movie is directly proportional to what you'll get out of it. If you allow it to, it will worm its way into your mind, gnawing at your subconscious, and certainly make you think twice about going into the forest alone. And as a horror fan, that is about the highest amount praise I can give. |

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed