While The Grand Budapest Hotel’s story is primarily a quirky, comedic mystery, the way in which Anderson presents this yarn simultaneously creates an enormously potent metanarrative. The Grand Budapest Hotel is a story about stories, and especially how susceptible they are to transmogrification whenever retold. This concept is brilliantly realized through the transformation of background locations presented throughout the movie.

“It is an extremely common mistake. People think the writer’s imagination is always at work, that he’s constantly inventing an endless supply of incidents and episodes; that he simply dreams up his stories out of thin air. In point of fact, the opposite is true. Once the public knows you’re a writer, they bring the characters and events to you… The incidents that follow were described to me exactly as I present them here, and in a wholly unexpected way.”

This statement is critical, as it is the only paltry evidence offered that any of the film’s events ever occurred. Everything that follows onscreen is nothing more than the visualization of the author’s story. This includes even the segments which are narrated by others, as they only exist as inhabitants of the author’s ongoing narrative. However, we’ll get to them a little later.

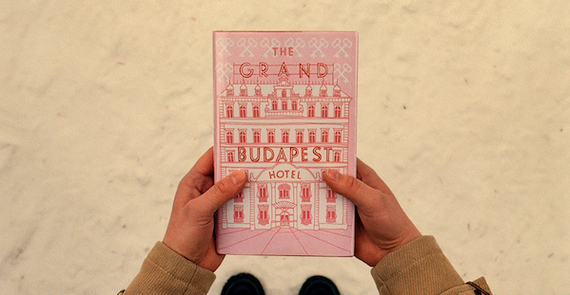

My reason for saying this goes back to the way that the Grand Budapest Hotel is introduced: not as a dilapidated building, nor as a flourishing getaway for elite clientele, but as an illustration on a book jacket. The dilapidated hotel only exists as part of the author’s recounting of a trip he allegedly took in the 60’s. Similarly, the hotel of the 30’s only exists as part of a story allegedly told to the author while on that trip. The establishing shots of the movie further reinforce the idea that the Grand Budapest Hotel exists only as a sort of metafiction within its universe, as it is only visible as a story, as a novel. Even at the movie’s end, the hotel bows out as it was introduced. The film’s final shot returns to the young woman still holding the book, as she sits beside the monument to the Author.

As such, she becomes a representative of the movie’s audience. Just as the reader has traveled to the author’s memorial and offered her key as ritual tribute, so too has the audience traveled to a theatre and offered their own admission for the privilege of exploring The Grand Budapest Hotel. Neither the audience nor the reader actually enters a real building, but that does nothing to prevent either from experiencing it. And I believe that’s the ultimate message of Anderson’s latest offering: when we invest ourselves in them, imaginary places do take on a strange sort of existence. Regardless of circumstance, whereabouts, or even reality we are all capable of reaching a shared destination through the venue of narrative. Author, Zero, Reader, Audience, we have all been guests within The Grand Budapest Hotel.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed