A lot of times the fight scenes in films become staples or descriptions of those films, and that is no mistake. Fights are inerrantly a clash of ideas or motives. The possibilities of ways to work with that in film are almost endless. Some of the ways filmmakers have thought to utilize fight scenes are things like progressing the plot, something baseline but still very important. Another way is to use the clash of two or more characters to better display the themes of the film, which makes it perfect for most audiences to understand. There is also the use of fights to highlight certain characters, and for them to have great moments that help to flesh them out. Fight scenes can also be used practically in a storytelling sense of giving the audience and the characters in the film information crucial due to the fight’s occurrence. The filmmakers can also use fight scenes as a way to construct awesome aesthetics, something all good films have, especially 21st century action movies. A fight scene is often the most memorable part of a film, and if done correctly, can elevate that film to even greater heights . A good fight could possibly be what makes certain films iconic for how that one scene impacts the rest of the film as a whole.

|

by Aaron Argot What makes fight scenes so appealing and have so much weight? People tend to love fight scenes because they are generally the scenes of the film that have the most and best action, and many people may write them off as just the carriers of action. Not that delivering action is at all a weak point or a shallow appreciation of fight scenes, but fights in films often have a greater meaning and purpose to them. Most people actually do notice these things, and sometimes the more it is hidden, the better. The best fights will elevate their respective film, and there are many ways fight scenes can do this. Some of those include the rather surface-level purpose of story progression, displaying the film’s themes, focusing on specific characters, using it as a means of exposition, and to show spectacular aesthetics. Most great fights, such as these 21st century fight scenes, have a combination of these, have all of these, or have even more purpose. The fight scene between Anakin Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi at the end of Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (George Lucas, 2005) shows how fight scenes can be used as a means of story progression. This is the most basic purpose of fight scenes, and generally every one should have this. This fight, however, while doing so much more, is the embodiment of that. This fight between Anakin and Obi-Wan is the bridge between the prequel and sequel trilogies, since this happens at the end of the last film of the prequels. The impact of this scene also comes from context, most viewers in 2005 had already seen the original trilogy and know that Anakin becomes Darth Vader, but they do not know how. Throughout each prequel film, that question is on viewers' minds, and is slowly answered through the three films. This fight after Anakin is named “Darth Vader,” yet still does not have the signature look. The end of the fight is where more insight is given into the look of Vader. It is also the outcome of this fight that would have shaped the entirety of the next three (and eventually six) movies, or could have had them not happen all together. And since everyone had everything connected, it changed the way people think of the original trilogy if only slightly due to what you learn about characters like Anakin and Obi-Wan. This one fight is the culmination of all that happened in the prequels, as well as foreshadows the second fight between them in Star Wars: A New Hope. I think that is the main part that makes this fight so impactful in the series. The fight also has the record for the longest sword fight in film history, which also might be why it is so iconic. Po utilizes his stark differences in battle In any one on one fight, it is often a fight between ideals and character differences, and in film, those ideals and differences are aligned with the overall themes as well. The fight between Po and Tai Lung at the end of Kung Fu Panda (Mark Osborne and John Stevenson, 2008) displays the themes of the film brilliantly. Po and Tai Lung are dramatic foils for one another, which contributes to the themes of this film. Tai Lung is the antagonist of the movie, is a leopard, and seemed to be very naturally gifted in the art of Kung Fu from an early age. In contrast, Po is the protagonist, is a panda, and was a fanboy of the kung fu masters, The Furious Five, before getting to train with them, being very bad at it at first. Uniqueness is a major theme of the film. Everyone is different so not everything is going to work the same way for everyone and everyone has different strengths, a lot of the times coming from our differences. Another theme is similar in that “there is no secret ingredient”, no secret to greatness, it all comes from you and what makes you unique. The fight starts off, with Tai Lung at the temple at the top of the mountain, fresh off of his victory against his and Po’s master, Shifu, who is also the thing that connects them. Po meets him at the top, but is visually winded by the climb, highlighting differences between them as Tai Lung basically has everything going for him, while Po seems to not. The entire battle between them is them fighting over something called “the dragon scroll”, which is said to hold the secret to limitless power, which Po already knows is blank and only a reflexive film. Throughout the fight, Tai Lung’s experience shows through his tendency to outmatch Po in traditional fighting techniques. However, Po’s panda nature, being plump and bouncy, allows him to use unique techniques to keep pace with Tai Lung, even defending him from the technique that beat the Furious Five. Eventually Tai Lung gets the scroll and discovers that it is blank, which angers him, something that could be described as his fatal flaw. This, paired with Po’s nature, allowed him to get the upper hand against Tai Lung, and ultimately defeat him. This fight is natural talent and entitlement vs. uniqueness and optimism, and with the film’s themes of uniqueness, it is clear who the victor would be. The fight’s expansion of the film’s core themes during the end of the film help it to display those themes more clearly, making a better overall film. Just like how Po and Tai Lung’s characters made the fight have more weight, characters in every fight and fight scene are truely what make or break it. Who they are and who they are fighting, as well as things like the reasons for doing so can all blend to make for fight scenes to have awesome character moments. Or the fight itself could be a character moment. One of those fights is Iron Man (Tony Stark) vs. Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War (Anthony and Joe Russo, 2018). This is a fight that has been, as a generous estimate, hyped up since 2012, since Thanos showed up in the end credits of The Avengers (2012). But for all of the hype surrounding this fight, it was relatively short, only lasting about two minutes, a testament to Thanos’ strength. Earlier in the movie, Tony states that Thanos has been inside his mind for six years. Going back to the hype statement I made, Tony’s statement here attributes the hype to more of an in-universe hype, as it is unlikely a lot of people in theatres were thinking about a Tony Stark vs. Thanos faceoff after the first Avengers. But with that context that Tony gives, you still feel the magnitude of six years of buildup when Tony and Thanos finally fight one on one. The PTSD that Tony felt after his experiences in the first Avengers has fueled a lot of his problems in MCU installments after that. Thanos was the source of the attack on New York in that film. So when Tony responds to Thanos’ statement saying they were both “cursed with knowledge”, with “my only curse is you”, it holds a lot of weight. And that is the moment that he finally has a clear head about what happened back then and is determined to fight that head on. So even though Thanos dispatched Tony in just two minutes, Tony won in that aspect. That is the reason why lots of people thought Tony was going to die in that instance, as it seemed like his character arc had more or less been completed. This scene is so important because of what we know about specifically Tony’s character and what he’s had to go through, and that six years of buildup also enhances the scene incredibly. The fight not only elevates the film, but the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe. Grey realizes what his body is capable of The next fight that uses fight scenes to communicate exposition comes from a film that came out in the same year, Upgrade (Leigh Whannell, 2018). The fight scene from this film is one that has been dubbed “The Kitchen Scene.” This scene is the first time that the main character, Grey, fights with the help of the artificial intelligence chip implanted in him. With verbal permission, the A.I. can take over his body and fight for him. In the film, Grey is trying to get revenge on the people who killed his wife and left him formally crippled, and he finds himself in the house of an enemy who then comes home. Grey starts off the fight unaided, and is very clearly losing. But, then the A.I. in his head says that he can help and he needs his permission in order to do so, which Grey gladly grants. What follows is the obvious improvement of Grey fighting prowess as his movements become almost comedically robotic, effortlessly overpowering and ultimately killing his adversary. The main purpose of this fight is to let Grey and the audience know that using the A.I. to fight is a real option in the future and could be very helpful in Grey’s mission to get revenge. This becomes a crucial detail, arguably the main detail, later in the film, and the film introduced it the best way it could, with a fight scene. Rengoku prepares an attack, displaying incredible visual effects The final fight I want to talk about is also the most recent, which is Rengoku vs. Akaza, from Demon Slayer: Kimestu no Yaiba - The Movie: Mugen Train (Haruo Sotozaki, 2020). This fight expertly explains how fight scenes in films can be used for aesthetic purposes. Of course, this fight also has elements of every other point previously mentioned, but what really stands out is how visually stunning it is. Mugen Train is an anime movie, and animation has incredible flexibility with all the technical aspects of filmmaking. With things like camerawork, in some ways it is easier to get the perfect shot. Being adapted from drawings not only gives you a good framework, but allows you basically take out the technical challenges of the aspects of some shots. But what shines through is the animation, the thing that sets it apart from live action movies. This circles back to the general premise that fight scenes are enjoyable because they are concentrated pockets of action, and this fight takes that to the extreme, until you are tilted back in your seat in awe. Music and sound design are also important factors in the aesthetics of a fight scene, the music that plays during the fight is exciting and works incredibly well. The sound effects of different fantasy-inspired attacks also work seamlessly with the animation. It is hard to explain aesthetics further than just saying they are incredible without seeing it, or without going into an incredible amount of detail. But, this fight scene illustrates perfectly how the aesthetics of a scene like this are just as important if not more important than the other aspects listed. The aesthetics can be described as the thing that sells you on the reality of what is happening, and the crazier the content the more challenging it is, but it is also that much more rewarding. The aesthetics of this fight help to accentuate all the other important aspects of the fight, making the fight itself, as well as the film, that much better.

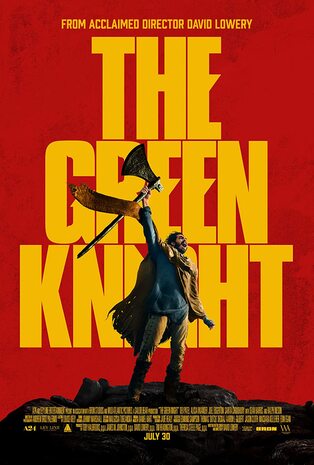

A lot of times the fight scenes in films become staples or descriptions of those films, and that is no mistake. Fights are inerrantly a clash of ideas or motives. The possibilities of ways to work with that in film are almost endless. Some of the ways filmmakers have thought to utilize fight scenes are things like progressing the plot, something baseline but still very important. Another way is to use the clash of two or more characters to better display the themes of the film, which makes it perfect for most audiences to understand. There is also the use of fights to highlight certain characters, and for them to have great moments that help to flesh them out. Fight scenes can also be used practically in a storytelling sense of giving the audience and the characters in the film information crucial due to the fight’s occurrence. The filmmakers can also use fight scenes as a way to construct awesome aesthetics, something all good films have, especially 21st century action movies. A fight scene is often the most memorable part of a film, and if done correctly, can elevate that film to even greater heights . A good fight could possibly be what makes certain films iconic for how that one scene impacts the rest of the film as a whole. by Mason Leaver It’s not every day that a film comes along like The Green Knight (2021). The entire premise is weird. The story is based on a folk tale over 600 years old, focusing on the journey of a young knight who enters a bargain with a mysterious green skinned knight. The plot itself is odd, and it doesn’t seem like the sort of tale that would appeal to a modern audience. However, The Green Knight somehow manages to make this story captivating. It’s strangest elements are actually some of its strongest, and writer/director/editor David Lowery dives head first into this Arthurian legend. The Green Knight is a miracle of a film- one which manages to create a sensational cinematic experience from the blueprint of something which, on paper, seems doomed to fail. One of the things which I most admire about Lowery’s process for The Green Knight is his willingness to take risks. There are tree-people, wandering naked giants, talking foxes, sorcerers, and so on. Yet all of these elements feel grounded in the world of the film- a strange, dark adaptation of the classic setting of King Arthur’s kingdom. The plot does not hold the audience’s hand. Instead, it forces the audience to interpret much of what is happening. Magic is mysterious and unexplained, and the viewer is left to guess at what exactly is happening at times. All of this leads to a final product which is very open to discussion, debate, and interpretation. It is a risky move for Lowery to leave so much to the audience, but it makes for a rewarding experience for the engaged viewer. One of the stranger elements of The Green Knight Another incredible aspect of The Green Knight is its use of color. Every frame of the film is masterfully composed. The village and castle of Camelot are rendered in harsh grey and brown tones, with high contrast lighting creating very interesting set pieces. As Gawain goes out on his adventure, the landscape is full of vibrant color. Each major plot point along Gawain’s journey is defined by a color scheme- red, yellow, white, green. This is certainly the largest project that Director of Photography Andrew Droz Palermo has worked on (Palermo previously worked with Lowery on Ghost Story (2017), and he shines through in this film. I could see an Oscar nomination for Best Cinematography for The Green Knight this year. I hope to see him work with Lowery again in the future. Audiences should be looking forward to Palermo’s next project, which is sure to be fantastic. Indeed, if his work in this film is any indicator, Palermo could go on to be a legend in the business. The use of color in The Green Knight The Green Knight continues to shine through in its thematic explorations. The film manages to strike a balance between inspiring a sense of wonder and a sense of existential dread. The film is thematically centered around the human awareness of our own finitude, what Martin Heidegger called being-toward-death. Gawain is forced to confront two possible scenarios: to live and contribute to the horrors of humanity or to die an honorable death. The film asks us to question whether we could stand in Gawain’s place, journeying bravely towards our deaths. The film also shows that leading a life of kindness, bravery and courage is hard, and it is rarely rewarding. Nevertheless, The Green Knight inspires us to live out such a life for the sake of the adventure itself. The titular Green Knight Despite all of these strengths, The Green Knight has still proven to be divisive among critics and audiences alike. Some seem to love the film, and others believe it’s pointless. I fall in the camp that says that The Green Knight is an excellent film. Many have commented on the film’s pacing as a serious problem. Green Knight often features lengthy sections of landscape shots, with Gawain travelling across a mythical England on his journey. While the film can be slow at times, the lengthy shots of Gawain’s journey are meant to set a tone and a mood for the viewer. I would liken these sequences to the many colorful space sequences from 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968). Indeed, I believe that many of the strengths of 2001 are on display in Green Knight. It’s pacing is largely similar- an episodic adventure with lengthy visual sections interspersed between. During these sections, the score similarly plays a vital role in setting the tone of the film. Both films explore deep questions and themes related to the human experience and human mortality. And both films offer an ambiguous ending which lends itself to discussion and interpretation by the audience. I realize that this is a bold claim, but my hope is that in time The Green Knight will come to be recognized as a film of a similar level of mastery. I would certainly recommend giving it a watch, and perhaps a rewatch.

by Samantha ShumaAs consumers of digital media, we have formed some assumptions about how films are structured. Especially with fictitious works, we’ve become accustomed to ignoring illogical aspects. This does have its limits, but we are more willing to believe impossibilities in order to enjoy a film. Our suspension of disbelief allows us to ignore fantastical elements and over the top plots in exchange for enjoying a film's story and characters. This also helps us follow along a film’s mapping of reality. We know that when a character wakes from bed that the scene previous was likely a dream sequence, and therefore didn’t really happen. Keeping these ideas in mind, we use our interpretation of film conventions as a tool to impose our own meaning onto a film’s narrative. Since so many film’s follow a certain structure of reality, our impositions are usually correct. We end up imposing meaning, that ends up revealing the truth or covering up what a film’s narrative intends to achieve. Relevant information is lost to preserve one’s assumption of film structure. Our tools of understanding a film’s narrative can be turned against us. Shutter Island (2010, Martin Scorsese) intends to use our ideas of film conventions and genre to displace our sense of reality. This remainder of this article contains spoilers for Shutter Island, reader discretion advised. U.S Marshal Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) and partner Chuck Alue (Mark Ruffalo) arrive on an island housing Ashecliffe Hospital, a mental institution, to solve the case of a missing patient, Rachel Solando. Teddy has not only come to solve the case, but has landed in the institution in the hopes of exposing it’s unethical practices on it’s patients. As he digs deeper into the possible truth, Teddy starts to believe that the head doctor, Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsly), hopes to turn him into a patient and keep him from sharing his findings. By the end, Teddy manages to get into where he believes the patients are taken to be lobotomized, a lighthouse on the far side of the island. It is there we discover the real truth, that Teddy, real name Andrew Laeddis, is a patient at Ashecliffe Hospital, who has just been through an elaborate role playing scenario, where the doctors hoped it would break him out of his psychosis. Since the film is shown through Teddy’s perspective, we see what he believes is real. Following his clues, his suspicions, most viewers would never guess the ending. Small actions over the course of the film build our suspicions, not to disbelieve Teddy, but other characters around him. Teddy’s paranoia spreads into the heart of the viewer, as “aspirin” causes Teddy to experience vivid dreams and intense hallucinations. It is in these moments where reality is hidden from the audience, and misleads us into following the story’s imaginary narrative. The dream sequences are obvious to discern, as they take place in places off of the island and are often a conversation between Teddy and someone who has died or doesn’t exist. Through these sequences, the film is drawing on the audience’s idea of a dream sequence as a means of misdirection. By stating that the dream world of Teddy talking to his dead wife is taking place within Teddy’s mind influences our assumption that the investigation of Rachel Solando is real. This line of dream and reality is drawn so clearly in the film, that his hallucinations become unnoticeable or at least are not questioned as being imagined. Towards the climax of the film, Teddy leaves Chuck behind to traverse the dangerous edge of the island to infiltrate the lighthouse. Unable to make it there due to the terrain, he heads back to retrieve his partner, only to spot his body, waves crashing on him and the rocky bottom of the cliff’s drop. Teddy climbs down to check on his partner, only to realize the body is only a pattern formed on the discoloration of the rocks. It’s easy to believe that the spot could’ve looked like a body from a great distance. We are given a reasonable excuse for Teddy’s misjudgement, widening our suspension of disbelief. Sneakily, the film is giving us more reasons to dismiss Teddy’s mistakes, and we slowly ignore more and more warning signs of Teddy’s mental illness. This analysis of Shutter Island techniques of misdirection is drawn from personal experience. Through an initial viewing, this belief of Teddy’s dire investigation felt real to the end. Always wanting to believe Teddy, anything that may have stuck out as odd never swayed my opinion. Even after the truth was revealed, I still did not want to believe Teddy was actually a patient at Ashecliffe Hospital. The film uses many strategies to shape the facts of the film. It is important to understand that not everyone will fall for the film’s tricks. To say that everyone will fall for it, or won’t ever notice the reveal early on is being too general. However, the belief that many film goers will believe Teddy through and through. The more movies you watch, the more you can make assumptions of how a movie will play out. Shutter Island shows itself as a drama, thriller, and a mystery. One would expect to see an exaggerated but interesting story along with endearing characters that will discover the culprit in the end. The film follows that expectation for a while, but ultimately pulls the curtain to show a completely different narrative. While misdirection is an excellent narrative tool that gives a film rewatchability, Shutter Island also uses our sense of film reality and narrative to call out our assumptions. The ending is only unclear to those who impose meaning based on past ideologies. Our ideas of how films are takes place over the intended artistic vision, leaving us to experience a lesser version of what the film hopes to show. Many must realize our assumptions do not construct the law of film, rather they restrict us from viewing a film’s meaning in its entirety. In this way, we are not far off from being like Teddy. He has assumptions about how the world works. His past trauma has led him to see the cruel through a cruel, broken gaze. In order for him to be a U.S Marshall solving a big case, there are events, people, and images that must exist. Whether consciously or not, Teddy is blocking out the truth or his mental illness to live in a reality that allows him to be free from his actual situation. Viewers who believe Teddy’s perspective will go along with his perspective, ignoring any reflags for the sake of preserving their assumptions of how the film will end.

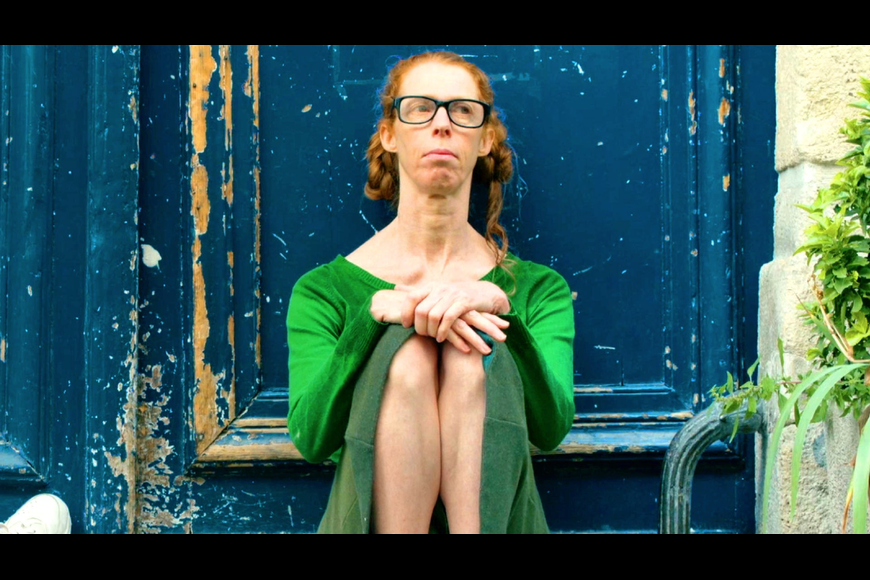

Even when watching films, ideology has the potential to undermine a film’s message. What we believe can be so heavily embedded into our minds that we aren’t able to accept any truth outside of that. That is what Shutter Island is proving to us. Those who always believe a film will play out in a certain way are blinding themselves to new and contrary takes on a film’s reality and story. Although our thoughts on a film’s structure may not have any lasting effects, not understanding or flat out ignoring something that doesn’t follow with what you already believe is a dangerous thing. It limits one from experiencing the world entirely and being open to new ideas. Shutter Island shows the consequences of ignoring the truth for the sake of what we may think is actually going on. Our ideas and personal truths shape our reality, and in Teddy's case, hides reality completely. by Ravi Ahuja Somewhere in the snowy north of Canada, a woman is telling a secret to her niece, “I’m going away to live in Paris.” The child agrees without much thought saying, “I’m going to live in Paris too.” Decades later, the child, Fiona, now a grown woman and a librarian, is still stuck in the same cold and desolate part of Canada. One day, the door blows open with the mail and Fiona receives word from her aunt Martha. After 48 years of living alone in Paris, ‘they’ want her to live in an assisted living facility. The letter ends with just the word “help”. And like that, Fiona’s journey to Paris begins. Fiona (Fiona Gordon) gets a picture taken in Paris Fiona’s trip to Paris is far from simple, losing her comically oversized rucksack on the first day, and being unable to contact or find her aunt. In the midst of her panic and desperation, she finds a few people who are able to help her, not the least of whom is a charming vagabond named Dom who comes across her rucksack. Dom is not the most convenient helping hand, often misunderstanding Fiona’s broken French and stealing her things upon first encounter. Still, the two are drawn together time and time again through both coincidence and their efforts to find Martha. Fiona Gordon and Dominique Abel are not just lead actors through this movie, but also co-writers, directors, and producers, Lost in Paris being their fourth film written together. While the side actors do a fine job, it is unmistakably Dom and Fiona’s movie, with their energy and personality dominating the feel and essence of the movie. Their acting is, as one might imagine, a perfect fit for the deadpan comedic writing of the film, with any scene featuring the both of them being sure to elicit a smile. Dom (Dominique Abel) and Fiona dance at a floating restaurant There isn’t too much more to say about the plot of Lost in Paris, but then that’s not its greatest draw. The movie is great fun, working off of constant physical and visual gags reminiscent of Chaplin and Tati. When the mail arrives in the opening, the door literally blows open with a gust of wind, causing everyone inside to exaggeratedly hang onto something. The acting, delivery, and setting of Lost in Paris also always work together to great comedic effect. Due to an innocent misunderstanding and some bad timing, Martha’s neighbor, Martin, is caught by Fiona and the police going through Martha’s underwear. Perhaps my favorite set-piece is the floating restaurant where Fiona and Dom meet. There are so many threads of visual, physical, awkward, and ironic humor interweaving through the whole dinner until the inevitable climax where Fiona realizes Dom has all of her belongings, and the pacing and humor works terrifically. Fiona sits in front of a door Besides just the old-school physical humor, Lost in Paris is also made great through its neat and colorful visual style. There is an emphasis on bright primary colors and clean, simple compositions. The overall effect is not unlike a watered down Wes Anderson, providing a similar innocent storybook feel to the story. I am reminded also of Amélie in how its bright, colorful visual style is used to help make the viewer fall in love with Paris as a city and a setting. Paris comes across as such a blend of small and big, modern and vintage, clean and dirty, and this is represented not only through the physical details on screen but the characters that live in it. Dom is a roguish, independent vagrant of Paris, and yet he falls in love with the polite and naïve woman from Canada. Dom, Martha (Emmanuelle Riva), and Fiona sitting on a beam Lost in Paris is short, fast-paced, and light, caring more about delighting its audience than making them think. Dominique Abel and Fiona Gordon do a fantastic job of keeping the film fun and fresh with their performances the whole way through. Fans of Tati and Chaplin, or anyone looking for a whimsical, old-fashioned rom-com should be sure to give the movie a watch. Lost in Paris is streaming now on certain Kanopy memberships.

By Mason Leaver Denis Villeneuve has consistently made films of breathtaking quality, including Prisoners (2013), Sicario (2015), and Arrival (2016). Yet, he is a less recognized name in film when compared with other directors. One of the reasons for this lack of popularity may be due to the fact that the director does not have a specific visual style, unlike contemporaries such as Wes Anderson or Quentin Tarantino (though Villeneuve’s partnership with cinematographer Roger Deakins has led to some visual similarities between his works). While Villeneuve’s filmography may not be held together by a common genre or mise-en-scene, it does still bear certain, less obvious commonalities. One of these commonalities is a repeated characteristic of his protagonists. Denis Villeneuve has demonstrated himself to be an auteur in the quality of his films by the common thematic exploration underlying his work, which examines isolation from a variety of perspectives and contexts. Detective Loki, framed in his cramped office space Last year I wrote a review of Prisoners and praised it for it’s storytelling and visuals. It is one of Villeneuve’s best films, and it highlights the start of the common trend surrounding the theme of isolation. The protagonists Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Dover (Hugh Jackman), are examples of isolated characters. Loki is a man who appears to be completely detached from others. He has given himself completely to his job as a detective. As the film progresses, Loki loses himself in his obsession to solve the case at the heart of the film. Dover, on the other hand, embodies a very different sort of isolation. Dover is a family man, and at the beginning of the movie is a very sociable and engaged person. However, after his daughter goes missing, Dover begins to isolate himself from his family, becoming equally obsessed with finding his kidnapped daughter. On screen, both Dover and Loki are often shown in cramped spaces- Dover in his truck, Loki behind his desk, both men restricted by the frame. Prisoners uses these two men as examples of the isolation which stems from obsession. Villeneuve (left) and Gyllenhaal (right) on the set of Enemy Enemy (2013) was released the same year as Prisoners, and also stars Jake Gyllenhaal. The film centers around Adam (Gyllenhaal), a history professor who discovers a man who looks exactly like him in a film. Adam attempts to track the man down, and begins to lose his mind in the process. Enemy, like Prisoners, examines loneliness and isolation, but Enemy examines two different forms of isolation. Firstly, the film deals with the suffering through a mental breakdown. Adam begins to question his own sanity and he begins to spiral further and further out of control. Yet, he finds out that others cannot relate to, or even understand, his condition. Villeneuve uses the two characters to show the isolation which comes from infidelity and lies. Adam sleeps in a small apartment with very little in it, and has no attachments, save for his girlfriend. Anthony (Gyllenhaal), Adam’s counterpart, is a successful actor with a wife. Yet both men are unsatisfied in their relationships, seeking more than what they have. The two characters come to represent a way of living a double life, with infidelity and selfishness at their core. The final shot of the film shows the ultimate isolation which one is forced into when they must confront their inner demons. Emily Blunt in Sicario Sicario (2015) follows Kate Macer (Emily Blunt), an FBI agent who becomes involved in a fight against the cartel. At the beginning of the film, Macer believes that she is fighting the good fight, and is optimistic about her role in serving justice. However, as she is recruited into a secretive mission to arrest high ranking members of the cartel, she crosses lines she never thought she would have to. Macer’s partners resort to torturing criminals for information and using Macer herself as bait in order to further their investigation. By the end of the film, Macer is disillusioned with the system that she has been working with. Nevertheless, she is forced to sign a document stating that everything that she and her team did was legal. Sicario depicts a sort of moral isolation. Macer is the only ethically upstanding person in a wholly corrupt system. As Macer continues with her mission, she becomes immersed in the corruption that she was initially revolted by, until she does not recognize herself- her moral compass tells her that the things she has done are wrong, yet she cannot take them back. Again, Villeneuve depicts an isolation in his protagonist- this time through the corruption of a system much larger than she is. Amy Adams stands alone in Arrival While Villeneuve’s previous work depicted isolation as a result of some negative circumstance, Arrival (2016) examines this experience as a result of epiphany. As Louise Banks (Amy Adams) begins to study the language of the aliens that have visited Earth, she begins to see the world differently. The aliens understand time in a different way than humans, able to see the present, past and future simultaneously. As Dr. Banks learns their language, she begins to be able to see the world from their perspective. She dreams in the alien language, and as she understands their language more thoroughly, she begins to see time as they do- past, present, and future all at once. The film shows us that as Banks continues her life, this new knowledge of time causes conflict with her husband. Banks is aware that their daughter will die young of an incurable disease, as she has seen it in the future. Nevertheless, Banks chooses to have the child. When Banks reveals this to her husband, it leads to a conflict which results in divorce. Ultimately, Banks’s enlightenment leads her to being isolated from the rest of humanity, as she is able to conceptualize the world in a way no one else can. K (Gosling) in his apartment with Joi (de Armas) Villeneuve’s most recent film, Blade Runner: 2049 (2017), tells the story of K (Ryan Gosling), a detective who tracks down rogue androids known as replicants. K lives a fairly depressing life. He lives in a small apartment, and has no social relationships. His only meaningful connection is to a computer program named Joi (Ani de Armas), who appears to him as a hologram. As the film continues, the hollowness of K’s life begins to become apparent to him, as all of the pseudo-relationships that he had with A.I become useless to him. Of all of Villeneuve’s films, Blade Runner: 2049 offers perhaps the least nuanced examination of isolation, though it is not any less impactful. Gosling captures the sorrow of living a lonely life, and the despair of discovering that one is even more alone than they thought. Villeneuve’s authorship does not come from any single stylistic consistency, but rather in the thematic exploration underlying all of his recent films. His work has been dedicated to exploring an aspect of human experience from a variety of perspectives. Some films, such as Sicario or Enemy offer an outlook on seclusion which is cynical, suggesting that we may become overwhelmed by our physical or moral isolation. Other films of his, such as Prisoners or Arrival offer a more hopeful view, depicting characters who still find hope and value even after experiencing an emotionally traumatizing event or an epiphany. No one except Villeneuve himself can say why it is that he seems to have this fixation with various forms of isolation in his protagonists. Regardless, this commitment to a consistent theme has shaped his career and helped him to become the impressive director that he is today. Villeneuve’s next film, Dune, is set to be released in theaters this October. Time will tell if Villeneuve has chosen to continue to explore the themes of isolation and loneliness in his newest film. For more on Villeneuve's career, take a look at our articles on Arrival, Prisoners, and Blade Runner: 2049

|

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed