However, films did not always use to be this fast cut. Throughout film history, there has been a steady progression from longer shots to quick cuts. In 1930 (and throughout the Classical Hollywood period), the average shot length was about 12 seconds. About 85 years later, the average shot length has been reduced to only 2.5 seconds, a fraction of the time from 1930. One possible reason for this shift is an ever- decreasing attention span from viewers. Every time a new shot is presented (or whenever the camera cuts) the audience is presented with something new and has to adjust to the new position or arrangement of the scene. This tends to keep them more interested. Longer shots, on the other hand, can cause viewers’ minds to wander as they maintain a single “view” (Wired).

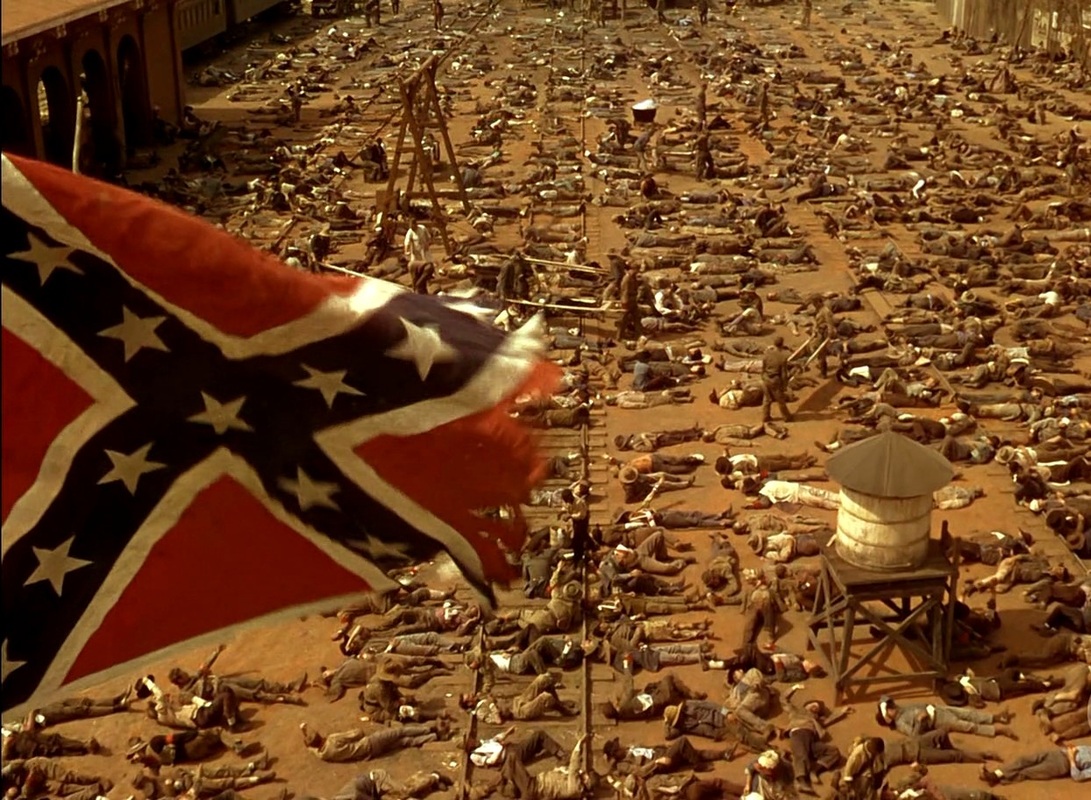

This can work both ways. Longer shots can cause viewers to become bored, but interestingly they can also have the complete opposite effect. It is important to note that long shots are the most natural type of shot in film—we as humans experience life all through one shot. We cannot cut to a different place or position instantaneously like in a film. This was one reason (in addition to cameras only being able to hold a certain amount of film) that the earliest films in cinema were a single shot. It was not until several years after the birth of cinema that cutting became a norm in film. The long shot, though it has a tendency to be boring for viewing, can also be equated with not blinking. The audience is fixated on what is onscreen and is not allowed to look away. In this respect, the long shot maintains viewers’ attention and has a greater impact on them than the conventional film today.

Though fast cutting is indeed the convention of modern films, there are a few examples of films that have heavily (and successfully) utilized long shots. Two recent examples include Gravity (Cuarón, 2013) and Birdman (Iñárritu, 2014), both of which had the same cinematographer (Emmanuel Lubezki). Gravity opens with a 17 minute shot and has an average shot length of 46 seconds throughout the film (Screenrant). Birdman, the Academy Award winner for Best Picture at this year’s Oscars, is edited to look like the entire film is one single take. Ultimately, there are only 16 visible cuts in the film (IMDB). The film took after a similar aesthetic used by Alfred Hitchcock in Rope (1948). In that film, Hitchcock (who was limited to 10 minutes for a take due to the amount of film the camera held) used methods such putting the camera to the back of a character and then cutting, maintaining the illusion that it is the same shot.

WORKS CITED

IMDB. 2015. 16 Apr. 2015. <http://www.imdb.com>.

Miller, Greg. “Data From A Century Of Cinema Reveals How Movies Have Evolved.” Wired. 8 Sept. 2014. 24 Apr. 2015. <http://www.wired.com/2014/09/cinema-is-evolving/>.

Schaeffer, Sandy. “Alfonso Cuaron’s ‘Gravity’ Features A 17-Minute Opening Shot.” Screenrant. 29 August 2013. 24 Apr. 2015. <http://screenrant.com/alfonsco-cuaron-gravity-opening-shot-long-takes-sandy-164262/>.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed