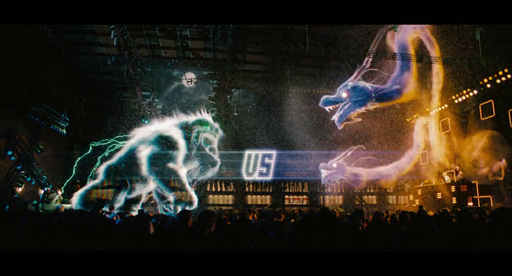

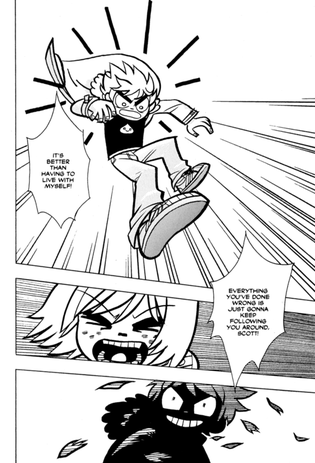

Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (Wright, 2010) is the film adaptation of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s award-winning graphic novel series - the story of Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera), a twenty-three-year-old who needs to get his life together. He has no job, lives in a small, dirty apartment across the street from his parents’ house, and is dating a seventeen-year old girl named Knives (Ellen Wong). Meanwhile, Scott encounters a girl from his dreams named Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) and instantly falls in love with her. However, before Scott can date Ramona, he needs to fight Ramona’s seven evil exes. Thus begins Scott’s journey to defeat all seven exes while learning to confront himself and his past actions.

| One could argue that, because of the film’s overall comedic tone, it would not matter if the animated visual style of the film looks silly compared to the live action elements. However, the film’s themes and subject matter make it seem like it is too comedic. Putting aside the numerous video game references and flashy fight scenes, the essential story of Scott Pilgrim is about confronting one’s past mistakes and maturing as a result. The film, as a result of taking more of a comedic tone, seems to downplay this theme compared to the graphic novel, which spends more time developing Scott’s problems with confronting his past and his failed relationships. |

Though one can argue that Scott Pilgrim could have done better as an animated film, the film that was made had clearly found an audience despite its financial failure.

Anderson, Tre’vell. “It’s a ‘Sausage Party’ at the Box Office.” Los Angeles Times, 14 Aug 2016. Accessed 20 Mar 2016.

Cargill, C. Robert. “Blu-Ray Review: Scott Pilgrim Is The Special Edition Blu-Ray We Usually Have To Wait Years For.” MTV News, 9 Nov 2010. Accessed 20 Mar 2016.

De Semlyen. “Sausage Party Review.” Empire Online, 2 Sep 2016. Accessed 20 Mar 2016.

Nordine, Michael. “Edgar Wright Live Tweets ‘Scott Pilgrim’ for Fans, Exposing Behind-the-Scenes Secrets.” IndieWire, 14 Aug 2016. Accessed 20 Mar 2016.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed