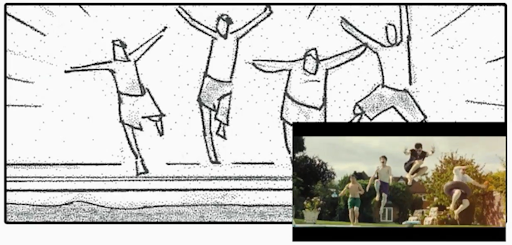

The main editing techniques that define Wright’s genre-breaking films are dramatic, jarring, often comedic cuts as well as interesting and unique transitions between shots. In addition to this, he is also meticulous in editing pre-production, that is, in storyboarding everything. This style of editing developed from his early days of filmmaking. At the start of his career, Wright didn’t have enough coverage for his film Dead Right (1993), and, as a consequence he didn’t have many choices when it came to editing (Edgar). In order to combat this problem and keep his films interesting, he had to use quick cuts and creative transitions, techniques that he continues to use and have become a defining characteristic of his films today.

In today’s filmmaking world, many filmmakers do not have a specific vision for how they want the editing of their film to add to the feel or mood of the film as a whole. In contrast, Edgar Wright takes the time to plan out every cut and transition in his film in order that each one adds to a theme or a mood he wants the film to portray. Wright uses the medium of film to its full advantage, creating some of the most innovative, entertaining, and beautiful films in modern cinema, something I hope to see more filmmakers utilize in the future.

“Edgar Wright on How He Writes and Directs His Movies | The Director's Chair.” YouTube, uploaded by StudioBinder, 7 December 2020, https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=fa_lP82gAZY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed