by Samantha Shuma

This analysis contains spoilers for 28 Weeks Later, which contains topics that may be disturbing for some readers. Discretion is advised.

A disease called the rage virus took hold of the population of Europe. It created a kind of ‘zombie,’ not interested in eating human flesh, but used biting as a means of spreading the virus. Eventually, only a population of infected remained, causing the infected to die of starvation and dehydration. It was at this point, the U.S military came in to dispose of all of the corpses. When it seemed that no infected remained, civilians were brought back to live inside a military base. Once the main characters were established, the military base collapsed. A new zombie outbreak took hold, leaving the civilians defenseless and all the decisions to the military. As the virus spread, the ultimate choice was made; total and utter annihilation.

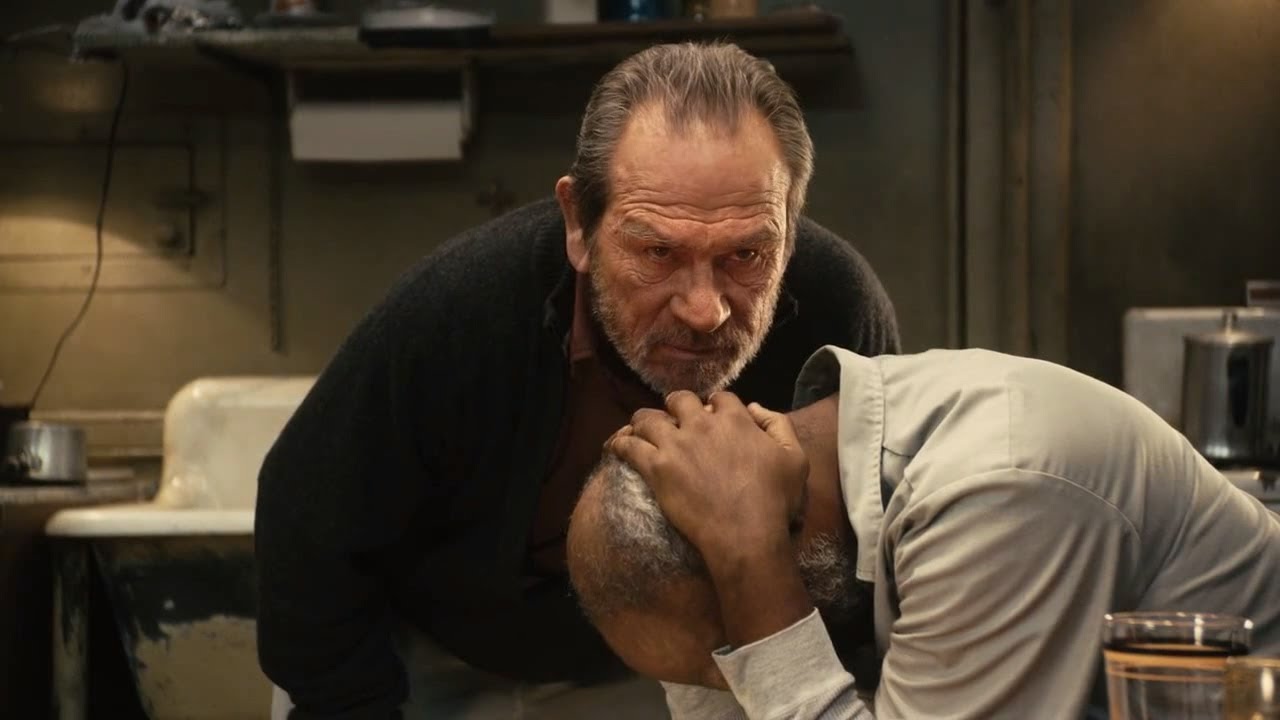

As it became impossible for infected and survivors to be distinguished through a sniper scope, Code Black was put into effect. The military’s procedures lead them to mass genocide, using snipers, fire bombing and chemical warfare as an attempt to stop the spread. The main characters aren’t only running away from the infected, but evading the tactics of the military to avoid certain death. Most of the soldiers are compliant with these methods except for Sergeant Doyle, one of the rooftop snipers. He chooses his moral compass over orders, helping the remaining survivors to safety. It is in his actions that we see the problem with procedure. If it was justifiable, why would a soldier choose to abandon their post? By Doyle leaving, he is demonstrating the morals go beyond procedure, contrasting the compliance of his comrades and commanding officers. If Doyle was complicit, this anti-proceduralist perspective would not land as well. The perspective would become less anti-proceduralist and more anti-human, giving points to a process that resulted in the death of thousands of people.

Secondly, the setting of the film completely detaches audiences from seeing that larger scope. The film is set in smaller areas, with most of the film being self contained within the military base. There is no tv coverage or any sense that there is a bigger world beyond what we see. It can be inferred, but the idea of a population bigger than what we see on screen is purposely avoided. 28 Weeks Later wants us to focus on the smaller picture, to relate to the characters and situations of the here and now. It distracts us from this idea of the ‘greater good,’ leading us to emotionally believe that this is all there is. The audience becomes so detached from the outside world of 28 Weeks Later that we end up not caring if the world lives or dies. Instead we care more about the people on screen and how they are being needlessly killed by the military.

Work Cited: Rocheleau J. (2011) Proceduralism. In: Chatterjee D.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Justice. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9160-5_367

RSS Feed

RSS Feed