- White

However, not all existentialist philosophers were willing to disregard suicide. Nietzche seemed to be much more open to the idea. One of Nietzche’s core philosophies, which he unpacked thoroughly in The Gay Science, was that most philosophers reason out of weakness, rather than strength. Most people, Nietzsche claimed, are too weak to face the cold hard truths of life: that there is no purpose in the world, that the strong eat the weak, and that God is a delusion. Nietzsche advocated that philosophers ought to philosophize out of a place of strength- coming to terms with the way the world is, and embracing it to make the best life for yourself that you could. Here, Nietzsche suggests that suicide would be a weakness- the weak man’s way of escaping from the reality of the world. However, in his later work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he spends some time discussing “voluntary death,” which he holds to actually be a great strength. To decide the time and method of one’s death was a decision that Nietzsche admired. Nietzsche had two conceptions of suicide: from weakness and from strength.

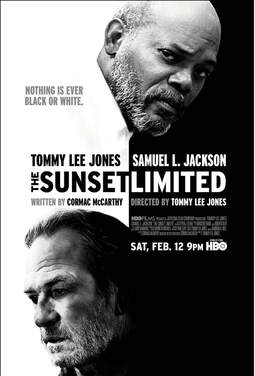

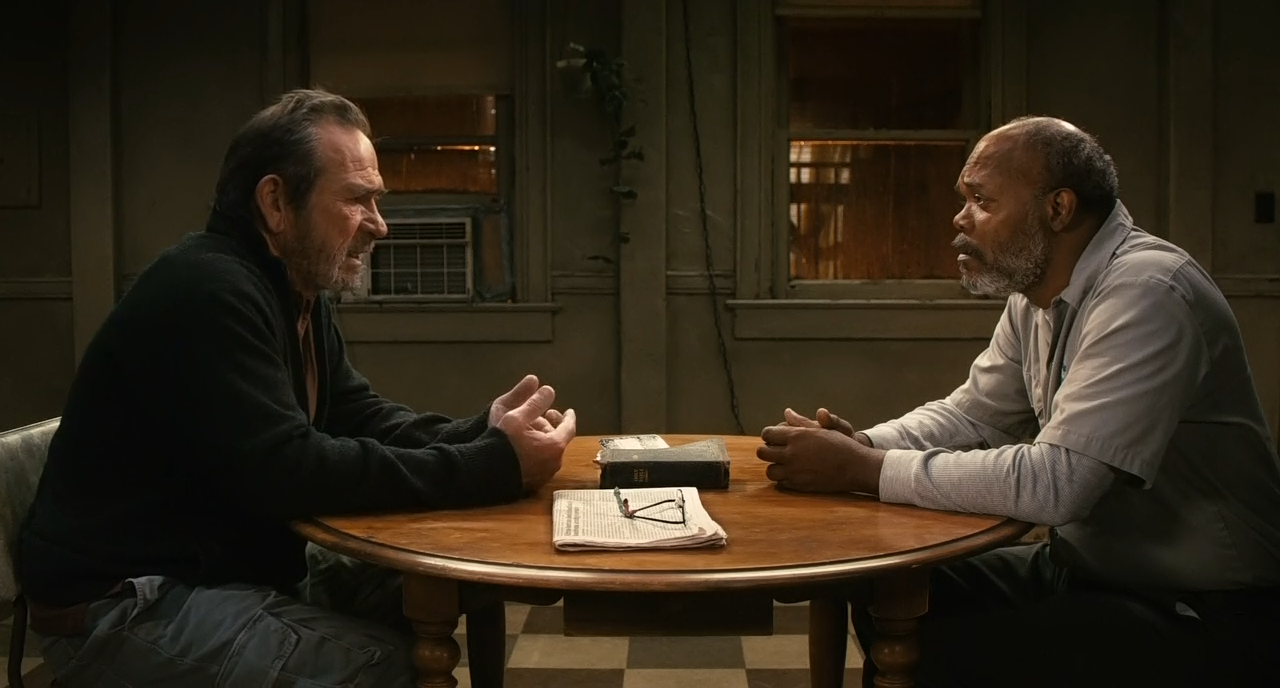

Is White’s attempt at suicide one from weakness or strength? Black and Nietzsche will agree that White’s desire for suicide comes from weakness. For Nietzsche, White’s desire to escape the cruelties of the world is an example of weakness. He would be strong if he was able to recognize the purposelessness of the world and continue to live despite it. For Black, White’s attempts at suicide come from a refusal to accept God’s love and an obsession with skepticism. White doesn’t desire to find the truth, instead, he is hellbent on doubting. As Black puts it, “a questioner wants the truth. A doubter wants to be told there ain't no such thing.” However, White disagrees with both of these men. He sees his desire for suicide as an act of strength, a denial of his biological programming. He thinks to desire death is to be seeing clearly. This is one of the fundamental points of White’s personal philosophy, and it is one area which creates a gulf between White and Black.

Sometimes faith might just be a case of not havin’ nothin’ else left.”- Black

Kierkegaard claimed that if there was no God, one must embrace nihilism as White does. One would expect him to then go on and say “But there is hope, because God exists!” But Kierkegaard’s solution to the problem of nihilism is not so simple. He says that the solution to suffering is found in part by the fact that God fashioned the Hero, who is capable of greatness. For Kierkegaard, Greatness came from three categories (a trichotomy of trichotomies). There was love; of the self, of others, and of God. There was expectation; of the possible, the eternal, and the impossible. And there was striving; with the world, with oneself, and with God. Each of these trichotomies represent a three-tiered notion of Greatness. The Hero was one who could ascend each step, and conquer them all. And the Hero can only do this in a world which includes suffering and evil. Then, Poets, like Kierkegaard himself, could write of the great deeds of these Heroes, and in doing so we could generate meaning and purpose in the world, through this striving and praising. Black reflects a similar idea here- how would one know that they’re happy if they’ve never suffered? Black takes inspiration from Kierkegaard, asking how one’s life could be fulfilling if one had never strived to overcome an obstacle? He suggests that pain is actually necessary for our growth.

Kierkegaard had a similar three-tiered notion of people, or three ways to live one’s life. At the bottom of this trichotomy was the Philistine. The Philistine loves what’s pleasurable and Earthly. He loves food, drink, and entertainment. White could be seen as a Philistine, with his love of the arts and culture. Then, there is the Knight of Infinite Resignation. This is the man who gives up what he has in order to sacrifice it to God. The Knight of Infinite Resignation is like a monk, giving up everything to strive for Godliness. Kierkegaard thought this was good, but it led someone who attempted it into misery, and that there was a better way to live. So, there was the Knight of Faith. The Knight of Faith is the man who gives up everything for God, and having given it up, holds all the more tightly to it. Kierkegaard’s archetypal example was Abraham, who was able to sacrifice his son to God, but after God relinquished his request for Isaac’s life, Abraham was able to love his son even more deeply. Black seems to be another example of the Knight of Faith that Kierkegaard describes. He has no concern for his material possessions, and is willing to let addicts take whatever they like from his house, and he delights in simple pleasures. Black has given everything up (as he puts it, faith is “not havin’ nothin’ left”) and now is free to hold on to and love things all the more strongly. There is a paradox at the heart of this philosophy, but both Kiekegaard and Black are fully aware of this. It is both letting go and holding on simultaneously that allows Black to live a life free of attachment, yet at the same time deeply love and care about White and the addicts in his tenement, and still trust God when it seems no good has come about from helping the addicts, or when he appears to have failed to save White. It’s a paradox!

Schopenhauer, Arthur, et al. The World as Will and Representation. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. Vintage International, 2018.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Bibliotech Press, 2020.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, et al. The Gay Science. Dover Publications, Inc., 2020.

Kierkegaard, Søren, et al. Fear and Trembling ; and, the Sickness unto Death. Princeton University Press, 2013.

Wicks, Robert. “Arthur Schopenhauer.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 11 May 2017, plato.stanford.edu/entries/schopenhauer/#Bib.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed