Martin Scorsese, in his newest film Silence (2016), wrestles with themes of faith in the midst of hardship and feeling abandoned by God. The story follows two Portuguese Jesuit priests, Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Garupe (Adam Driver), who travel to Japan to search for their mentor Ferreira (Liam Neeson). Along their journey, they meet with the Japanese Christians who face persecution under a stubborn, murderous inquisitor (Issei Ogata). While Rodrigues watches as his brothers and sisters in the Lord are murdered, he questions why God would allow God’s children to suffer for their faithfulness.

|

By Emmanuel Gundran Martin Scorsese, in his newest film Silence (2016), wrestles with themes of faith in the midst of hardship and feeling abandoned by God. The story follows two Portuguese Jesuit priests, Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Garupe (Adam Driver), who travel to Japan to search for their mentor Ferreira (Liam Neeson). Along their journey, they meet with the Japanese Christians who face persecution under a stubborn, murderous inquisitor (Issei Ogata). While Rodrigues watches as his brothers and sisters in the Lord are murdered, he questions why God would allow God’s children to suffer for their faithfulness. It is heart-breaking yet so compelling to watch a man like Rodrigues be constantly beaten down, both physically and spiritually, but still continue onward for the people he cares for. At the beginning, he is an idealistic, devout Christian who wants to see the man who mentored him again. Over the course of the film, he is weathered down by persecution to the point of him being ridden with sickness and malnutrition. When he finally meets Ferreira after a long journey into the heart of Japan, he is crushed to find out that his own mentor has literally stepped on the face of Jesus and joined the Buddhist faith, helping to burn Christianity out of Japan. If there are any major flaws the foremost would be its length. The film is over two and a half hours long, and it definitely shows. There are sequences that tend to hold on quiet or serious moments or to focus on scenery. Moments like these do make the film live up to its own title. However, I think that the slower pace of the film helped me get a better sense of the importance of each scene. One of the ways through which the Japanese Inquisition force the Christians to recant their faith is through stepping on an image of Jesus. These scenes slow down to focus on the crucial decision that each Christian must make, whether to deny Jesus or face their deaths. Even Rodrigues must make this choice that will be his ultimate test after all that he had faced to reach Japan. I believe it is appropriate to have these slower moments to let the film’s heavier themes solidify in audiences' minds. As a Christian myself, I felt that I could resonate with Rodrigues’ own questions of faith. Though many Christians will not have to face the same kind of persecution and doubts as Rodrigues, circumstances in Christians’ lives will force them to think critically about what they believe in. One may not have faced the deaths of their loved one before their eyes, but others may have encountered a belief that was different from their own and caused them to see the world from a different perspective and caused them to question their own worldview. Like Rodrigues, sometimes I am faced with the uncomfortable moments of God’s silence, moments where either God does not give an answer or has an answer that does not satisfy my questioning. These are the moments that Martin Scorsese wanted to capture through Silence and cause audiences, especially those who are Christian, to get a grasp on difficult questions that the film brings up on faith and sacrifice.

By Emmanuel Gundran American culture’s changing socio-political climate has changed radically over the past one hundred years. These changes have also shaped the way that filmmakers craft their work, whether they encourage the current culture’s trends or challenge them. A film like Zero Dark Thirty (Bigelow, 2012) re-enacts, in gruesome detail, the hunt for Osama Bin Laden in 2011, practically making it a reactionary tale of the events. However, a film does not need to have overt references to real-life events for it to be rooted in a particular time and place in history. It is very clear that Mean Girls (Waters, 2004), from the fashion to the pop culture references and even the technology (or lack thereof), is a product of the mid-2000’s culture. Films such as these preserve culture, like a time capsule of sorts, and show either what filmmakers or audiences at the time valued about their culture. The same holds very true for animated films, and, in addition, it shows what filmmakers at the time wanted to communicate to children, the primary audience for most animated films. Animated films in the 2010’s, by analyzing their culture and content, portray the decade as an era of mass connection, individuality, and emotional vulnerability. Due to the growing accessibility and overall usefulness of electronic devices, especially smartphones, American culture in the 2010’s has become more interconnected than ever before. Marshall McLuhan correctly predicted that technology would allow everyone to become more connected with one another, and compares what society has become to “a global village” (63). Films like Wreck-it Ralph (Jackman, 2012) and The Lego Movie (Lord and Miller, 2014) are the result of inter-connectedness in pop culture because of their inclusion of characters that the filmmakers knew their target audiences would instantly recognize. The Lego Movie features Batman (Will Arnett) from DC Comics as one of its main protagonists while other familiar characters like Dumbledore from the Harry Potter franchise, Han Solo from the Star Wars franchise, and Gandalf from the Lord of the Rings franchise play supporting roles throughout the film. Meanwhile, Wreck-it Ralph has the title character (played by John C. Reilly) meeting up with Bowser from the Super Mario Bros games and Zangief (Rich Moore) from the Street Fighter games in a ‘villains anonymous’ meeting. The way that these characters from vastly different franchises are able to crossover with such ease demonstrates how online social media has created a space for fans of all of these franchises to connect with one other. Users on the Internet can post on online forums where they can discuss their favorite games, shows, or movies, create a web of other fans, and even encourage outsiders to join their fandom. While American society in the 2010’s has become very inter-connected through online media, it is also very adamant about idividuality and self-discovery. Ever since the country’s beginnings, individuality has been a strong American trait. The Declaration of Independence was written as a means for the country to individualize itself from Great Britain and recognize its citizens’ rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness (US 1776).” Brave (Andrews, Chapman, and Purcell, 2012) and Moana (Clements and Musker, 2016) both display through their protagonists that aggressive individuality that American’s have. Merida (Kelly MacDonald) of Brave is a great example of individuality at work, as she rebels against her family’s marital customs to forge her own path using her bravery and skill with a bow. Similarly, Moana (Auli’i Cravalho) breaks with her family’s comfortable, isolationist traditions to explore the open seas and follow the adventurous traditions of her ancestors. Both Merida and Moana do eventually return to their families later on to make amends, emphasizing the importance of family in an individual’s life. However, each of them do so in different ways. While Brave ends with Merida reconciling with her family and strengthening her relationship with them, thus emphasizing a greater need for community rather than isolation, Moana ends with Moana not only returning to her family but also shaping her tribe’s culture through her strength and courage, thus showing that someone can inspire bravery in others. Both films deal with the issue of individuality and one’s relationship to their community in different ways but recognize that one cannot always live in total isolation. Finally, there is the idea of allowing one’s emotions to shine through and show kindness to others that is becoming more important to American society. In an interview with The Atlantic’s Julie Beck in 2015, psychologist David Caruso states that American culture has a “relentless drive to mask the expression of our true underlying feelings" ("How to Get Better At Expressing Emotions"). It’s this drive that’s demonstrated in Disney and Pixar’s Inside Out (Doctor, 2015). The film’s main characters are the five basic emotions of a young girl named Riley Andersen (Kaitlyn Dias) who help her through her day-to-day activities. Throughout the film, Sadness (Phyllis Smith) is pushed further and further away from the other emotions when they she causes Riley to have unpleasant moments in her life. This perfectly represents the mask that Caruso says is so common in America. To paint a better picture oneself as a strong, self-reliant individual, one may hide their sadness or other negative emotions behind a mask of happiness or strength. However, Inside Out teaches that sadness cannot be held for long, and that people have an innate need for catharsis, an outlet for embracing sorrow. Before Riley can run away from home on a buss and give in to depression, Sadness is given back control of her thoughts. Thus, Riley runs back home to her parents from the bus and tearfully hugs them both, finally giving her a moment of catharsis. Because culture is always changing, one has to wonder how films, especially animated films, will change with the times. With racial equality, gender dynamics, and political correctness becoming more relevant issues, perhaps more films such as Zootopia (Howard and Moore, 2016) will come out of the woodwork to address them. Then, who knows how other films will respond to, or even reshape, the culture moving forward? These films preserve the values and challenges of a generation, and will give future generations a perspective of where American culture was and where it is going. Works Cited: Beck, Julie. “How to Get Better at Expressing Emotions.” The Atlantic, 18 Nov. 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/11/how-to-get-better-at-expressing-emotions/416493/ McLuhan, Marshall. The Medium is the Massage. Ginko Press Inc., 1967. By Jack Waterman In general, horror-comedies haven’t been doing particularly well as of late. To be sure, there will occasionally be an independent horror-drama that will sweep through film festivals winning all kinds of accolades, but rarely will there be anything that is both scary and funny. Admittedly, some of this could be that the overall quality of horror films seems to have dropped somewhat over the past couple of years. However, this doesn’t fully explain why horror-comedies just don’t seem to work anymore. Most them are either not scary, not funny, or both, and there doesn’t seem to be any real explanation for why. Even less common is a well-made horror comedy that is also well received by both critics and audience members. The New Zealand horror-comedy HouseBound (Johnstone, 2014) is one of those rare films. It’s hilarious, terrifying, brutal, and touching all at the same time. It was extremely good; so good in fact, that I found myself subconsciously avoiding other horror-comedies after seeing it. For the longest time, I didn’t understand why. It wasn’t until I saw IT (Muschietti, 2017) a few weeks back that I finally discovered how to fully articulate my thoughts about the current state of horror-comedies, and more importantly, what can be done to fix them. First off, it’s critical to establish what a horror movie is and what a comedy movie is. In layman’s terms, the former is intended to make you shriek in terror, and the latter is intended to make you shriek with laughter. Right off the bat, there’s a distinct similarity between the two: both genres of film are carefully formulated to elicit powerful emotions and physiological responses. But therein lies the rub; how does one make a film that is both frightening and funny when these two adjectives are often regarded as being each other’s antonym? Well, in some cases, that is exactly the point. In movies such as the classic Ghostbusters (Reitman, 1984), the film alternates between scariness and hilarity in precisely the right proportions. Just before one of them starts becoming too prevalent, a joke or a scare in thrown into the mix and turns the tables on everything. For instance, at the beginning of the movie, the Ghostbusters come face to face with the ghost of a librarian. After a humorous debate about how to best approach it, they attempt to pounce on the ghost, only to have the apparition transform into a horrifying monstrosity and screech like a banshee at them. Just as the audience is becoming comfortable with the comedic tone of the film, it pulls a 180 and makes everyone in the audience jump out of their seats. The fear when making horror-comedy seems to be that putting in something too funny or too scary will disrupt the flow of the sequence and yank the viewer out of the movie. Indeed, this is the delicate balancing act that is so hard to pull off, and ultimately what distinguishes a good horror-comedy from a bad one. A horrifying sight in an otherwise humorous scene. In The Horror Spoofs of Abbott and Costello, author Jeffrey S. Miller divvies the horror-comedy subgenre up further into black comedy, parody, and spoof (Miller, 1). Black comedy is characterized by dark, morbid content being played for laughs, as opposed to being sacrosanct (example: Evil Dead 2 (Raimi, 1987)). A horror parody typically isn’t scary in the slightest, but is rather a deconstruction of the horror genre, and is almost exclusively intended to be humorous (example: Shaun of the Dead (Wright, 2004)). A horror spoof tends to treat the horror genre and its various sub-genres with more love and affection than a horror parody, and they generally contain fear and fancy in equal proportions. Spoofs are typically what most people think of when they hear “horror-comedy”, and this is largely the category that HouseBound falls under. I mentioned earlier that seeing IT was the catalyst in figuring out what my problem is with (modern) horror-comedies. As previously noted, IT is a fantastic movie. However, one thing that I didn’t talk about in my review is that, while the movie is quite scary and quite funny, it isn’t really both of those simultaneously. It is, as I mentioned, a comedic horror movie rather than a pure-blooded horror-comedy. For instance, the film has some fairly spooky sequences in the beginning in which Pennywise is shape shifting into incarnations of the main characters’ deepest fears. Yet the moment the sequences conclude, the movie immediately cuts to the other main characters making sex jokes. It’s not so much that these scenes aren’t scary or funny, but rather that they have nothing to do with each other. And again, this is ultimately the most glaring issue with modern horror-comedies: their inability to properly blend humor and horror. In the masterfully crafted An American Werewolf in London (Landis, 1981), the two build off of and inform each other; nutty hilarity morphs into hair-raising frights, and moments of heart-stopping terror give way to outrageous (and somewhat twisted) laughs. "I didn't mean to call you a meatloaf, Jack!" Here’s a more specific example directly from HouseBound. Near the climax of the movie, the main character Kylie’s probation officer, Amos, is attempting to pry open an old wooden door. The film’s antagonist, serial killer Dennis, is sneaking up behind him clutching a butcher’s knife. Amos is muttering something about needing a thin, metal bar of some kind. Dennis now is standing directly behind Amos, and is seconds away from stabbing him. The suspense is at a fever pitch. Then without missing a beat, Amos turns around, grabs the knife out of Dennis’s hand, and with a casual “Thanks.”, uses it to crack open the door.

Why does this scene work so well? How is something so incredibly scary able to be transformed into something so hilarious? To put it bluntly, it’s because of audience expectations. Expectancy violation is one the most fundamental principles of both comedy and horror. In both areas, there is a gradual buildup to a pop or mini-climax (that is to say, a punchline/scare). In some cases, the buildup may be prolonged significantly to release as much tension as possible when the pop finally comes (or in the case of films like The Blair Witch Project (Myrick and Sánchez, 1999), it may never come). The kicker is that it’s not as simple as plugging things into an equation and getting an audience reaction. Certain styles of buildups and pops are more commonly used then others, and audiences learn to recognize these styles pretty quickly if they are used too often. What we see used in Housebound is a somewhat stereotypical buildup to a very creative and wacky pop that is the complete inverse of what we were anticipating. Tension is still released, but in a surprising and unexpected way. This is what is meant by an expectation violation. HouseBound truly is a rare gem indeed; it’s one of the last of a dying breed of classic horror-comedies. There are many lessons that can be gleaned from its cleverly structured plot and pops. Who knows, perhaps there will someday be a resurgence of excellent horror-comedy. Until then, it’s comforting to know that, while the sub-genre is struggling, it is far from dead. Citation Miller, Jeffrey S. The horror spoofs of Abbott and Costello: a critical assessment of the comedy teams monster films. Jefferson, NC, McFarland & Co., 2004, pp. 1-3 Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) ponders a difficult situation in Mexico (Logan - Mangold, 2017) by Megan Hess Like many fans of the X-Men cinematic universe, I was distressed when I first heard Hugh Jackman was wrapping up his portrayal of the hard-hearted, cigar-smoking, Canadian mutant Logan James Howlett (better known as Wolverine) with one final film. Jackman’s Wolverine is comparable to Heath Ledger’s Joker in how he took a rabidly popular fan-favorite character – one of the most frustrating, complex, and interesting original members of the X-Men – and made him come alive like the character stepped out of a comic book and onto the screen, but still kept the performance completely his own. With his good looks and raw talent, Jackman drove the franchise so much that he eventually got to have his own spinoff movies. The poor quality of the two films that precede Logan - X-Men Origins: Wolverine (Hood, 2009) and The Wolverine (Mangold, 2013) – is part of what makes Logan so incredible. X-Men Origins: Wolverine is quite possibly the worst film Jackman has ever done. Knowing Game of Thrones showrunner David Benioff helped write the screenplay makes me weep. This pustule of a film also features Ryan Reynolds as Wade Wilson (Deadpool); the fight scene between him and Jackman on top of a nuclear reactor is by far the most painful and ridiculous moment of a movie comprised of many painful and ridiculous moments strung together. Fortunately, critics were more pleased with The Wolverine than they had been with X-Men Origins: Wolverine, and Logan improved on the formula yet again, bringing it to a perfect close. Many aspects of Logan are interchangable with the other installments. The Wolverine movies are, as a rule, bloodier than the X-Men movies. Logan takes this to the extreme, as if the writers got paid extra for brainstorming creative ways for characters to die. (This does lead to a few beautiful moments, but mostly, it’s overkill). Logan has an excess of side characters, but, unlike the prior movies, uses them well. I was most impressed by Stephen Merchant’s Caliban, an albino mutant whose mutation allows him to sense and locate other mutants. The makeup effects and costuming for his character really stood out as excellent. Merchant is somewhat familiar to a niche of American audiences – Big Bang Theory watchers – since he guest-starred on a season of the popular CBS show as Amy Farrah Fowler’s (the phenomenally funny Mayim Bialik) new boyfriend, Dave, after her brief split with Sheldon Cooper (Jim Parsons). However, since his character only had a 3-episode arc, it was not really a good example of his capabilities. After Logan, I hope Merchant has more success in American cinema; he reminds me of a British Alan Tudyk. Logan and Caliban (Stephen Merchant, right) (Logan - Mangold, 2017) More than its judicious use of side characters, it’s the way Logan brings emotion back into the Wolverine franchise that makes it so stellar. The social-psychological aspect of the X-Men franchise, especially in its best-executed moments – X2 (Singer, 2003), X-Men: First Class (Vaughn, 2011) and X-Men: Days of Future Past (Singer, 2014) for example - is what sets them apart from their competitors. The Wolverine movies always got more wrapped up in the spurting blood and flashing steel claws. As previously mentioned, Logan has those elements in abundance, but also isn’t afraid to get sentimental. Wolverine’s character is known for keeping his friends and emotions at a distance, but, in Logan, he holds both a little closer. The self-sacrificing, parental Logan in this movie isn’t an entirely new character – look at his relationship with Rogue (Anna Paquin) in X-Men (Singer, 2000) X2 (Singer, 2003) and X-Men: Last Stand (Ratner, 2006), and his actions at the end of Last Stand with Jean Grey (Famke Janssen) – but it’s a more direct and nuanced one that drives the movie’s most heart-tugging plot points. Certain moments in Logan are just as sad or sadder than Erik (Michael Fassbender) paralyzing Charles (James McAvoy) in X-Men First Class or when Jean Grey\Dark Phoenix kills Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart) in Last Stand. Logan is not a movie to watch alone, and I believe it’s not meant to be watched that way. Consider it a wake for the Wolverine franchise, or Jackman at his peak in the role. Logan is a dream end, and other superhero franchises should take note of its success.

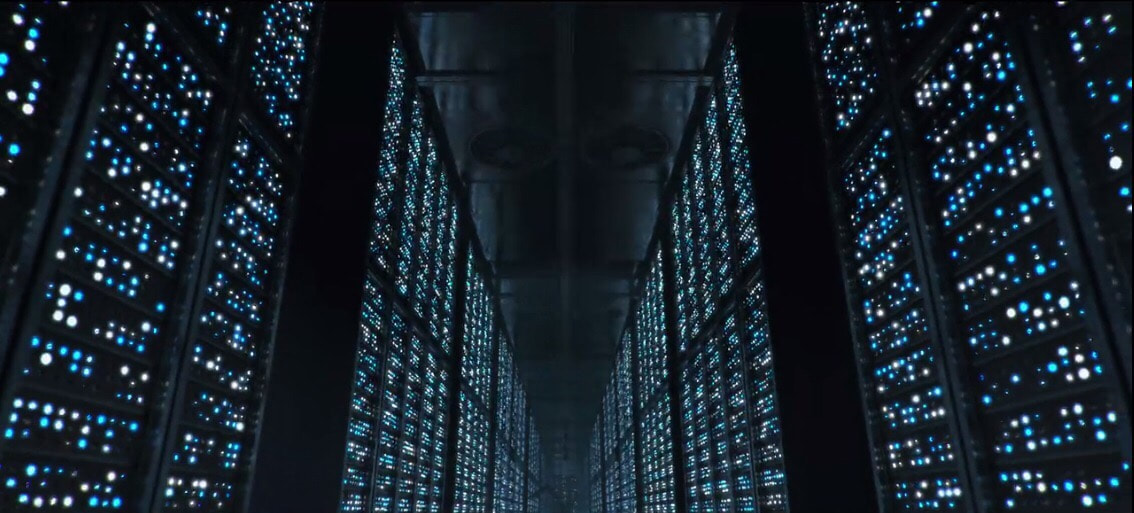

By Nathan Simms “And the Emmy goes to Black Mirror: ‘San Junipero’,” as these words rang out from the Emmy stage, Netflix made science fiction history. The episode actually won two awards that night, one for outstanding TV movie and another for outstanding writing for a movie. As Netflix’s premiere Sci-Fi anthology show, Black Mirror shows the way that technology can impact society in the future. The vast majority of the episodes are bleak and negative critiques of that future, with dark and thought-provoking themes. It seems only fitting that one of the more positive episodes garnered two Emmy’s. “San Junipero” demonstrates what a LGBTQ+ relationship looks like on a mainstream television show and raises questions about the validity of simulated worlds. “San Junipero” opens with Yorkie, the twenty-something female protagonist, who goes to a bar in 1987 and meets Kelly, a whirlwind on the dance floor. The two strike up a friendship after Yorkie helps fend off one of Kelly’s ex-boyfriends. From there they continue to spend time together, every weekend, until exactly midnight-when the simulation starts over. Both Yorkie and Kelly go to San Junipero via digital uplinks, and our limited by the time the computer allots. Much like a massive online game, they enter the simulated world for just a few hours, and are forced to exit. Outside of the computer, Yorkie and Kelly are actually in their late 60’s and in retirement homes. They use San Junipero to escape from their realities. The city of San Junipero looks like any other coastal town, but it is nothing more than a picturesque digital retirement home. 85% of the residents are deceased, their consciences being uploaded to the computer. Oether elderly people can visit, like Yorkie and Kelly, but they are limited to trail periods. Both the residents and the temporary visitors can choose what year they want to visit, allowing them to recapture their youth in both physical and temporal terms. Although San Junipero is a love story, the science fiction background creates a unique outlook on our future. LGBTQ+ individuals are rarely seen in Sci-fi films, besides the couple in this summer’s Alien: Covenant, I cannot think of a notable character in a Science-Fiction film who is not of a heterosexual orientation. The majority of onscreen couples are heterosexual or single, with a ton of science-fiction films not showing sexuality at all. Seeing a happy homosexual couple in this episode is important because it reflects our reality. Despite the controversy that often surrounds gay rights, there are people of different sexual orientations, and the display of them in the near future allows individuals to identify with characters just like them. After visiting, Yorkie decides she’s ready to “pass over” and become a permanent resident of San Junipero. Before her body dies, Kelly decides to visit her in the real world. The older Kelly takes a self-driving vehicle to Yorkie’s retirement home, where she finds the 61 year-old, paralyzed Yorkie. A worker at the home tells Kelly that Yorkie has been paralyzed for 40 years, the result of a car accident after Yorkie’s parents rejected her sexual orientation. In the simulation, Yorkie regains her ability to walk and speak as well as freedom to express her sexuality without fear of society. The clear tragedy of San Junipero is that Yorkie is unable to be herself until after she’s already dead. The terms of her societal experience put her into her condition and she waited for 40 years for something better. San Junipero was that something better, but she could not fully experience it until she received what amounts to medically-assisted suicide. “San Junipero” brings a new light to the discussion on gay rights and equality. It is a bluntly stated critique of our society that Yorkie was only able to find freedom in death. At the end, Yorkie and Kelly reunite as permanent residents and drive off into a literal sunset as Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven Is a Place on Earth” plays. This is the happiest ending of any of Black Mirror’s few episodes, but the triumphant montage is intercut with scenes of a giant warehouse. Inside are countless blinking lights, all plugged into stacks of servers, tended to by giant robotic arms. Yorkie and Kelly together transcended their human bodies and are now stored as pulsing electronic signals. Inside the simulation they seem happy, but the filmmakers are asking if their happiness is real. We cannot know if Kelly and Yorkie are legitimately “human” in a simulation, but the optimistic nature of the finale signals that it may not actually matter.

|

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed