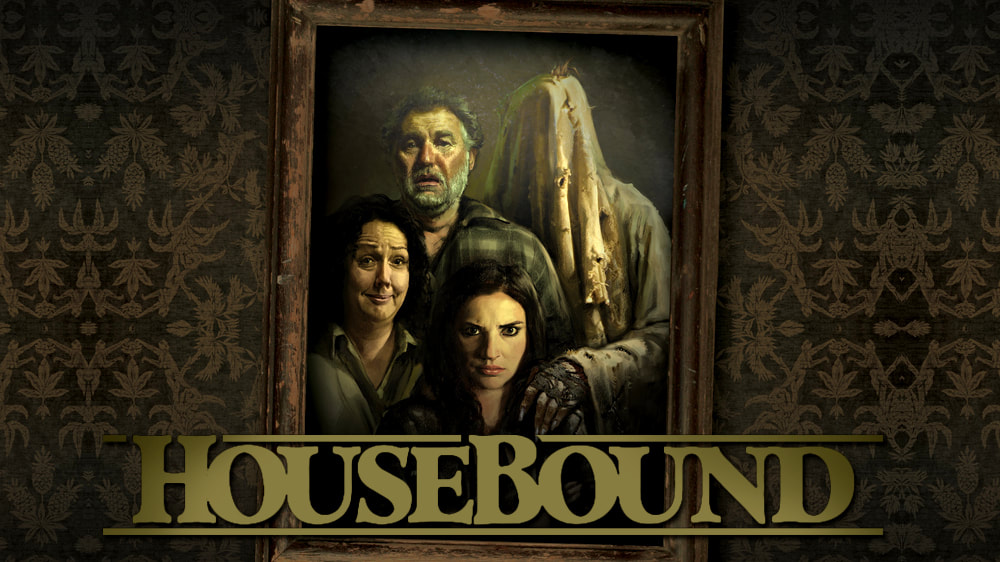

In general, horror-comedies haven’t been doing particularly well as of late. To be sure, there will occasionally be an independent horror-drama that will sweep through film festivals winning all kinds of accolades, but rarely will there be anything that is both scary and funny. Admittedly, some of this could be that the overall quality of horror films seems to have dropped somewhat over the past couple of years. However, this doesn’t fully explain why horror-comedies just don’t seem to work anymore. Most them are either not scary, not funny, or both, and there doesn’t seem to be any real explanation for why. Even less common is a well-made horror comedy that is also well received by both critics and audience members. The New Zealand horror-comedy HouseBound (Johnstone, 2014) is one of those rare films. It’s hilarious, terrifying, brutal, and touching all at the same time. It was extremely good; so good in fact, that I found myself subconsciously avoiding other horror-comedies after seeing it. For the longest time, I didn’t understand why. It wasn’t until I saw IT (Muschietti, 2017) a few weeks back that I finally discovered how to fully articulate my thoughts about the current state of horror-comedies, and more importantly, what can be done to fix them.

First off, it’s critical to establish what a horror movie is and what a comedy movie is. In layman’s terms, the former is intended to make you shriek in terror, and the latter is intended to make you shriek with laughter. Right off the bat, there’s a distinct similarity between the two: both genres of film are carefully formulated to elicit powerful emotions and physiological responses. But therein lies the rub; how does one make a film that is both frightening and funny when these two adjectives are often regarded as being each other’s antonym? Well, in some cases, that is exactly the point. In movies such as the classic Ghostbusters (Reitman, 1984), the film alternates between scariness and hilarity in precisely the right proportions. Just before one of them starts becoming too prevalent, a joke or a scare in thrown into the mix and turns the tables on everything. For instance, at the beginning of the movie, the Ghostbusters come face to face with the ghost of a librarian. After a humorous debate about how to best approach it, they attempt to pounce on the ghost, only to have the apparition transform into a horrifying monstrosity and screech like a banshee at them. Just as the audience is becoming comfortable with the comedic tone of the film, it pulls a 180 and makes everyone in the audience jump out of their seats. The fear when making horror-comedy seems to be that putting in something too funny or too scary will disrupt the flow of the sequence and yank the viewer out of the movie. Indeed, this is the delicate balancing act that is so hard to pull off, and ultimately what distinguishes a good horror-comedy from a bad one.

I mentioned earlier that seeing IT was the catalyst in figuring out what my problem is with (modern) horror-comedies. As previously noted, IT is a fantastic movie. However, one thing that I didn’t talk about in my review is that, while the movie is quite scary and quite funny, it isn’t really both of those simultaneously. It is, as I mentioned, a comedic horror movie rather than a pure-blooded horror-comedy. For instance, the film has some fairly spooky sequences in the beginning in which Pennywise is shape shifting into incarnations of the main characters’ deepest fears. Yet the moment the sequences conclude, the movie immediately cuts to the other main characters making sex jokes. It’s not so much that these scenes aren’t scary or funny, but rather that they have nothing to do with each other. And again, this is ultimately the most glaring issue with modern horror-comedies: their inability to properly blend humor and horror. In the masterfully crafted An American Werewolf in London (Landis, 1981), the two build off of and inform each other; nutty hilarity morphs into hair-raising frights, and moments of heart-stopping terror give way to outrageous (and somewhat twisted) laughs.

Why does this scene work so well? How is something so incredibly scary able to be transformed into something so hilarious? To put it bluntly, it’s because of audience expectations. Expectancy violation is one the most fundamental principles of both comedy and horror. In both areas, there is a gradual buildup to a pop or mini-climax (that is to say, a punchline/scare). In some cases, the buildup may be prolonged significantly to release as much tension as possible when the pop finally comes (or in the case of films like The Blair Witch Project (Myrick and Sánchez, 1999), it may never come). The kicker is that it’s not as simple as plugging things into an equation and getting an audience reaction. Certain styles of buildups and pops are more commonly used then others, and audiences learn to recognize these styles pretty quickly if they are used too often. What we see used in Housebound is a somewhat stereotypical buildup to a very creative and wacky pop that is the complete inverse of what we were anticipating. Tension is still released, but in a surprising and unexpected way. This is what is meant by an expectation violation.

HouseBound truly is a rare gem indeed; it’s one of the last of a dying breed of classic horror-comedies. There are many lessons that can be gleaned from its cleverly structured plot and pops. Who knows, perhaps there will someday be a resurgence of excellent horror-comedy. Until then, it’s comforting to know that, while the sub-genre is struggling, it is far from dead.

Citation

Miller, Jeffrey S. The horror spoofs of Abbott and Costello: a critical assessment of the comedy teams monster films. Jefferson, NC, McFarland & Co., 2004, pp. 1-3

RSS Feed

RSS Feed