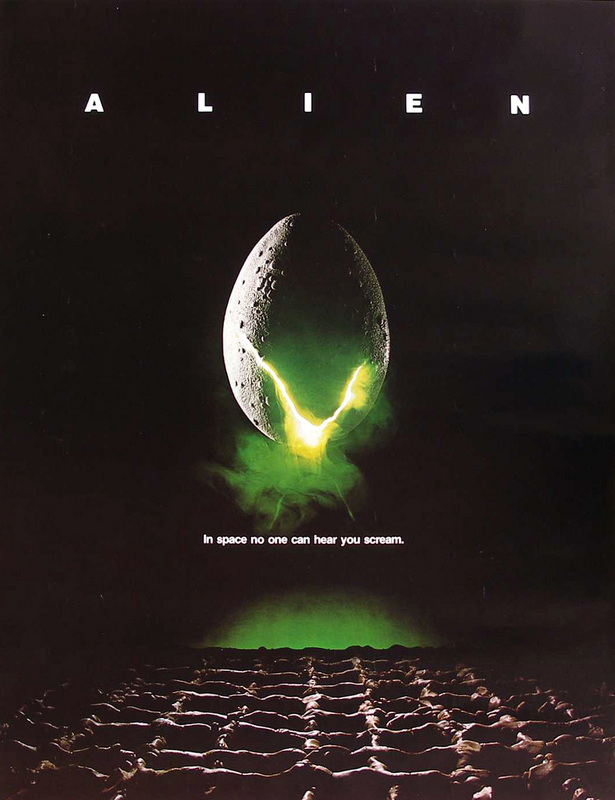

It is commonly thought that the cast had no idea whatsoever what was going to take place during the scene. This is only partly true. The cast knew what was going to happen…but only to a certain extent. According to Veronica Cartwright, who played “Lambert” in the film, the crew involved in the setup showed the actors a “mockup” of what would happen, but the mockup didn’t show how the gag would be accomplished. According to Sigourney Weaver, who played the main character “Ellen Ripley”, all the script said was, “This thing emerges” (The Guardian). So the actors knew in a very general way what would happen, but they didn’t have any degree of detail. One thing is very clear: none of the actors expected to be sprayed with blood when the alien creature emerged (side note: real pig’s blood was used for the scene).

For the scene, a fake chest was used for John Hurt’s character “Kane.” Hurt was underneath the table, with his neck appearing to be connected to the fake chest. Director Ridley Scott wanted the scene to be as authentic as possible, so real organs were bought from a butcher shop and stuffed inside the fake chest cavity. Hoses were also used to help pump and spray the blood when the creature exploded from Hurt’s chest.

Four cameras were used for shooting the scene. Two technicians were under the table operating the compressed blood machine that would spray blood everywhere upon the alien’s emergence. Initially, however, the scene didn’t go as planned. When the alien puppet that was used was unable to penetrate John Hurt’s shirt, Ridley Scott yelled to cut. After cutting Hurt’s t-shirt a little more, shooting resumed. When the alien finally emerged, the whole cast was shocked and terrified. Cartwright commented, “We all start leaning forward again and all of a sudden it comes out. I tell you, none of us expected it. It came out and twisted around.” Sigourney Weaver also noted, “All I could think of was John [Hurt], frankly. I wasn’t even thinking that we were making a movie” (The Guardian). The sudden outburst and explosion of blood certainly caught all the actors off guard. After being sprayed directly in the face with the pig’s blood, actress Veronica Cartwright actually passed out. Also, after the scene, Yaphet Kotto (Parker), went into his room and wouldn’t talk to anybody.

WORKS CITED

“The making of Alien’s Chestburster scene”. The Guardian. 12 Oct. 2009. 12 April 2014. <http://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/oct/13/making-of-alien-chestburster>.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed