Interestingly, the relationship between boxing and cinema extends all the way back to 1894, when William KL Dickson of the Thomas Edison Company filmed a contest between Jack Cushing and Mike Leonard. Although the film was roughly thirty seconds long, it forged a bond between boxing and cinema that has since remained strong. But what ultimately solidified the dramatic legacy of the pugilist was the decision to adapt true stories of boxers to the screen. By depicting the world of legendary boxers, cinema exposed viewers to the plights that these boxers encountered outside of the ring and focused on the sport’s extensive ties to organized crime in its early years, which ultimately gave boxers a much deeper and darker nature. This subsequently provided viewers with a haunting understanding of why boxers might opt to endure and dish out the brutal punishment that they do in their line of work. The Harder They Fall (Robson, 1956), provides an excellent example of this darker underside to the sport that was revealed in early boxing films.

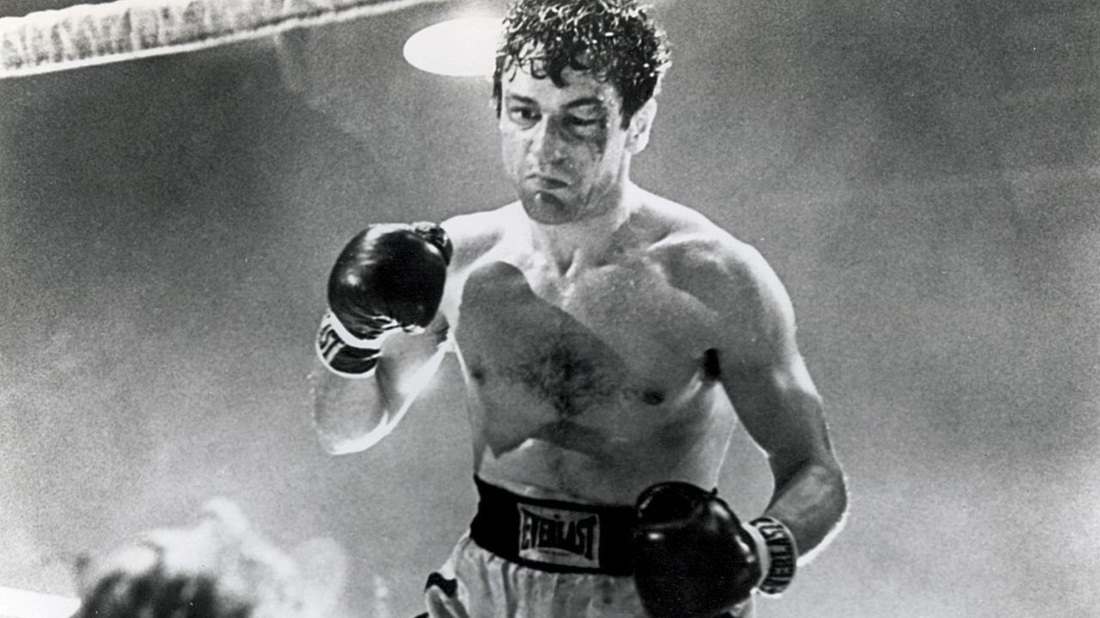

In other cases, such as On the Waterfront (Kazan, 1954), the world of boxing effectively functions as a quiet backdrop to develop a washed-up character in a story primarily driven by its attempts to expose issues pertaining to class structure and fears of Communist expansion at the time. However, there is perhaps no boxing film that has communicated its significance to the world of cinema more than Martin Scorsese’s 1980 landmark film, Raging Bull. Not only is Raging Bull widely regarded as one of the greatest sports films ever made, but it is also critically regarded as one of the greatest American films of all-time. Through the presentation of Jake LaMotta’s self-destructive journey through life, Raging Bull powerfully communicates various problems pertaining to masculinity and sexual jealousy, and how violent tendencies plague the boxer both in and out of the ring. Of comparable importance to the world of cinema, but with an entirely different message, Rocky (Avildsen, 1976) communicated something that transcended the limits of the ring; a hero is someone with perseverance who can “go the distance.”

Even though the popularity of the sport itself has substantially waned in recent years, the boxing film genre has not shown any clear indicators of an impending decline in popularity. In fact, with films like Cinderella Man (Howard, 2005), The Fighter (Russell, 2010), and the winner of the 2005 Academy Award for Best Picture, Million Dollar Baby (Eastwood, 2004), the longevity of the boxing film genre seems quite promising. Ultimately, by continuing to shed light on the internal struggles that boxers must cope with outside of the ring, the boxing film genre should continue to hold onto its title as the most successfully adapted sport to the realm of cinema.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed