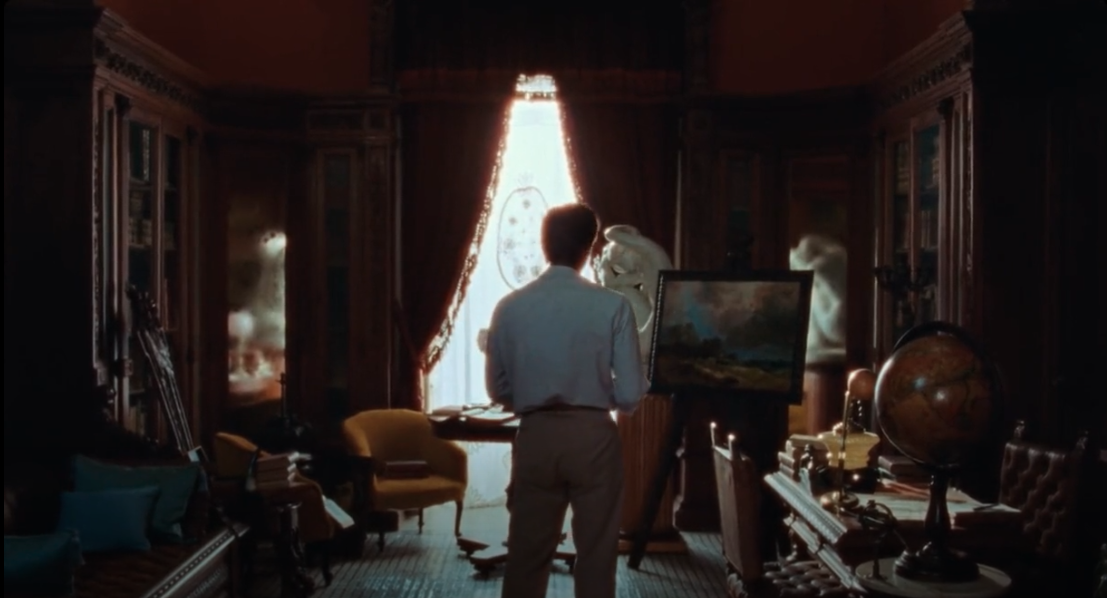

On Inisherin, Colm is known as a man of enviable culture: he's a skilled musician and has been able to built the reputation of almost being an academic, his interest for all things that lie beyond the rocky Irish coast manifesting itself through the purchase of Japanese men-yoroi masks and African trumpet horns, enough to decorate his entire house. His knowledge is so vast that the people of the island are quite surprised that the man has not yet tried his fortune on the mainland too, and would rather spend his days playing the fiddle at the local pub and chatting with Pádraic, who is but a lowly countryman with no interest for music and even less for culture and literature.

It's because of these different personalities of theirs, that the people of the island aren't surprised, when Pádraic begins moaning about his friend refusing to speak to him, merely asking if they're "rowing" and telling him to just follow Colm's wish of being left alone once and for all. Despite everybody telling him so, Pádraic cannot bring himself to follow their words: Colm is his best friend, has been so for years, so he needs to know if the man is enraged at him because of something he has said or done.

In one last, brief conversation Colm concedes to him, Pádraic discovers that the reason why the man doesn't want to be his friend anymore because he now considers Pádraic to be dull, and fears that his dullness might hinder his future as a brilliant player and composer. Colm wants to be surrounded by people like him, people who are cultured and engaging, who will stimulate his desire to produce art. Pádraic, as nice as he might be, doesn't inspire anything in him, and therefore he now considers spending time with him as a waste.

Still, Pádraic is unable to leave Colm alone, and the man, frustrated with the other's constant need of attentions, decides to threaten him: "I have a set of shears at home, and each time you bother me from this day on, I will take those shears and I'll take one of me fingers off with them, and I will give that finger to ya, a finger from me left hand, me fiddle hand, and each day you bother me more, another I'll take off and I'll give you, until you see sense enough to stop, or until I've no fingers left."

Although this promise of self-violence leaves Pádraic shocked, he cannot control his desire to go bother Colm again, and he falls into temptation twice. The first time, when he's drunk, he approaches his former friend and asks him why being nice isn't enough anymore (Colm's answer, snobbish, further highlights the distance between the two men, as he says: "Ah, well... I suppose niceness doesn't last then, does it, Pádraic? But I tell ya something that does last? Music lasts. And paintings last. And poetry lasts."); the second time, he does so because of the information that Dominic wrongly reports to him, according to which Colm, after the scene Pádraic caused in the pub the night before, now considers him to be better than before. Both times, Colm takes a pair of shearing scissors and cuts off his fingers (the former time amputating only one finger of his left hand, the latter all of the remaining ones), throwing them at the door of Páedar and Siobhán's house so that they both can see the damage their family caused.

Already saddened by the departure of Siobhán, Pádraic goes home to find his dear donkey, Jenny, dead: while he was at the port, she found Colm's fingers and began nibbling on them, accidentally choking on one of them and suffocating. Truly enraged for the first time, Pádraic finds Colm at the pub and it's his turn to threaten him: "Your fat fingers killed me little donkey today. [...] Yeah, no, I'm not joking you. So tomorrow, Sunday, God's day, around two, I'm going to call up to your house, and I'm going to set fire to it, and hopefully you'll still be inside of it. But I won't be checking either way."

The following day, as he said at the pub, Pádraic loads his cart with gasoline and oil lamps and drives it to Colm's house, taking the man's dog before it can get injured and then douses his friend's house. Before setting it on fire, he checks through the windows for Colm and even seeing him sitting on a stool, smoking, he goes through with his plan, then watching the house be engulfed by flames.

Later, as he's standing on the beach that faces the coasts of the mainland, Colm reaches him, dirtied with tar but still alive. While they're there, watching the water and the land that war ravaged for more than a year, Colm makes a comment about how the conflict must be finally coming to an end, prompting Pádric into responding by saying that, from some fights, there is no coming back from.

From a visual point of view, the specter is represented by Mrs McCormick (Sheila Flitton), an elderly woman who lives in a cottage by the lake. Clad in black clothes that are traditional to Irish costume, she wanders in front of the Súilleabháin siblings whenever they are in pain or uncertain about their future.

When the siblings are first introduced, they are already grieving: in a conversation between Siobhán and Mrs McCormick, it's revealed that both of their parents died seven years prior in an unspecified sudden accident that left them alone; their impossibility to process their parents' death is shown by having them still sleeping their childhood bedroom, in twin beds that are almost too small for them to rest comfortably in. Throughout the story, this feeling of oppression and sorrow only hightens: for Pádraic, such feelings are born out of his broken friendship with Colm (and, later on, caused by Jenny's death), while Siobhán is already grieving herself, as she worries she will be stuck on Inisherin for her entire life, cursed into sharing all human interactions with that group of bitter island people.

His sudden hatred for Pádric is nothing more than self-hatred he expresses by attacking his best friend, putting him at fault for his own actions. Colm already carries the desire of cutting his own fingers off, an extreme measure to put a drastic end to his career of fiddle player before what he fears the most can happen: discover that he's not as talented enough to make it.

At the end of the movie, despite the both of them having lost everything because of one another (Pádraic lost his sister and his donkey, Colm lost his fingers and his home), Pádraic speaks the truth: some conflicts cannot be solved, and not everything that has happened between them can be ignored so that things can go back the way they were. In the same way, the conflict that took place between 1922 and 1923 changed the history of Ireland forever, making it impossible for its citizens to resume how they used to live before it.

As Colm said towards the end of the story, now earth is struck by enough grief for the banshees watch, amused and silent, as humans only bring more pain and death to one another.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed