Hunched over a voice recorder, Martin Eden (Luca Marinelli) mumbles his disappointment for modern society: "Those who build prisons express themselves with far less clarity than those who build freedom," he says in a drawl, exhaustion making it impossible for him to keep his eyes open. As he begins to fold over the table, unable to support the invisible weight he carries onto his shoulders, the scene abruptly cuts to stock footage from the early Twentieth Century, people smiling and waving at the camera, excited by the novelty of the contraption in front of them.

Marcello, a young Italian director whose body of work mostly focuses on documentaries, took on the ambitious task of adapting Jack London's final (and most autobiographical) novel for the screen, modifying it to fit a reality he could better understand and represent. Rather than being set in the San Francisco of the early Twentieth Century, Marcello's Martin Eden takes place in the Southern Italy of an unspecified decade (the presence of flared pants and tightly collared shirts hints at it being set after the Protests of 1968, a time of collective disillusionment for all those who believed revolution was possible), but is nevertheless able to explore the story and themes presented in its source material.

His destiny changes when, the morning after a party, he saves a boy, Arturo Orsini (Giustiniano Alpi), from being beaten, and is invited to his house for lunch as a sign of gratitude. Arturo is not like the ones Martin was raised alongside with, initiated to the harsh lives of manual laborers while still in childhood: he was born into a wealthy family who owns mansions, cars, cushy lifestyles that allow for its members to spend their lives focusing on academia. In Arturo's home, Martin is incredibly out of place, his rugged clothes and swarthy appearance unable to fit within the pristine and delicately constructed world of the Orsinis, a world in which everything is fragile, pale, expensive.

Although Martin is self-aware enough to recognize the class differences between him and the Orsinis, his ignorance allows for him to deceive himself into thing that they, just like anybody else he has previously encountered, can be charmed into thinking of him as a peer with a couple of good chats.

It's Elena (Jessica Cressy), Arturo's older sister, who makes him realize that this is not the case: after a brief conversation before lunch, in which the woman corrects his French pronunciation in a rather patronizing manner, Martin finds himself smitten and tries to seduce her (in the scene right before this one, Martin was shown effortlessly flirting with another girl, indicating that, for him, it's almost a habit, to use his charms and good looks for such purpose), but Elena immediately makes it clear that she won't stoop down her social position for anyone.

If Martin doesn't abandon his working class roots and rises to Elena's social class, she will never pursue a relationship with him.

However, what began as a journey to seduce a woman quickly evolves into one of self-discovery: through his process of schooling, Martin reaches a new level of self-awareness, of understanding of the social class divide between him and the Orsinis, of the concepts of proletariat and bourgeoisie.

Frustrated by his incapability to earn an elementary school license, Martin sets a new goal for himself: he'll become a writer, and when his first work will be published, he'll go back to Elena and will ask for her hand, strong of his worth as an intellectual. Cargo ships and Naples abandoned in favor of a simple life spent renting a room in the house of a widowed woman, Martin writes and writes and writes, struggling by as he chips at all his savings, getting more and more discouraged as all the newspapers and publishing houses he submits his works to don't deem it worthy of publication

Even the letters he receives from Elena are a form of disappointment: she thinks his dream of gaining social footing by becoming an author is foolish, useless, and although the snippets of his writing he sends her are beautifully written, they are not in her taste. The differences between them are solidified through an in person encounter that takes place when Martin travels back to Naples for a few days: even now that he is educated and can mingle with the friends of the Orsinis without much effort, Elena thinks of the themes of his writing as crass, violent, unable to depict reality. Frustrated, Martin grabs the woman's arm and jostles her around, dragging her through the streets he was raised in, where prostitutes and thieves abound, scaring her.

The reality Elena is accustomed to is simply one that is for the very few, her privilege made her blind and deaf to the struggles of the normal people, and even now that Martin has presented her with them, she would still prefer to close her eyes and ignore them, finding them undignified.

Fully disillusioned with Elena and the feelings he has for her, Martin abandons her and goes back to writing.

Now that his talent has been discovered, Martin becomes an overnight sensation, pays back all his debts, keeps writing while the flame still burns. With the help of Russ Brissenden (Carlo Cecchi), an eccentric older writer he met at a party held by the Orsinis, he navigates the world of success, and learns an extremely important lesson: he has to fight for those who can't, for those who, just like Martin at the beginning of the story, don't recognize the inferiority their ignorance and low economic status gives them within society. Martin's unique position in the world, that of a man who was able to rise against all odds, allows him to be their voice. "How many people do you see starve to death or go to jail because they're nothing but wretches, slaves, ignorant and stupid?" Russ asks him. "Fight for them, Martin."

Initially, he tries to do so, participating in conferences organized by unions, but soon enough his face and words are noticed by a journalist who writes an article about him, leading to Martin being misunderstood and disliked by many for his political views, which are branded as being those of a communist. The last spark of the Martin that was dies when Russ suddenly commits suicide, leaving him to navigate the world that wants to tear him apart in complete solitude.

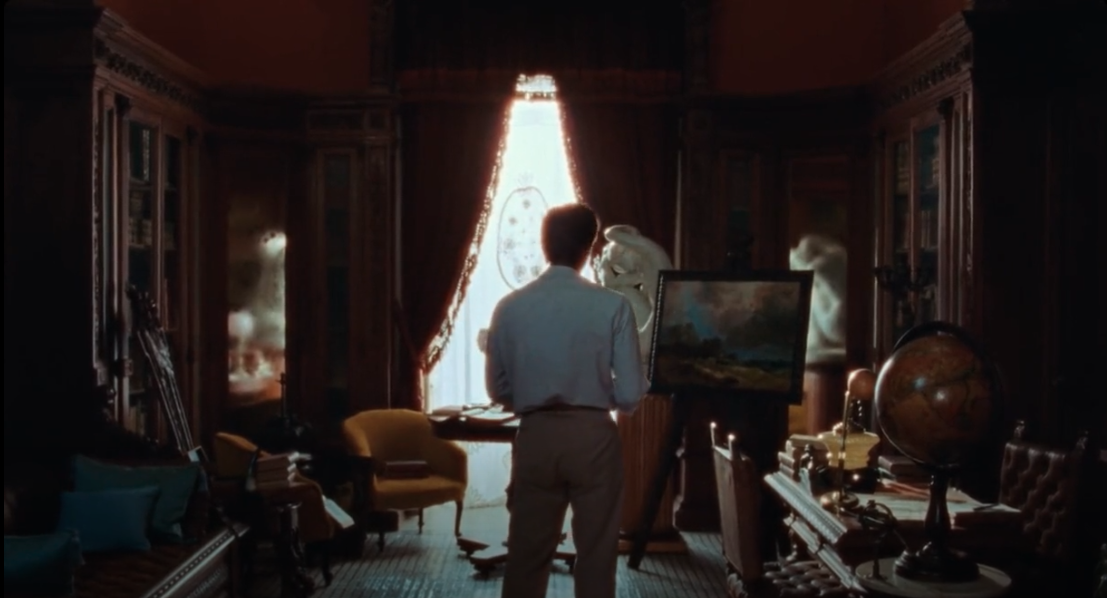

Life embitters him, further makes him sink into disillusionment. Now wealthy, he purchases a luxurious apartment that resembles the Orsinis' mansion and dresses only in the finest of clothes, bleaches his hair to be blonde (a characteristic that, at the beginning of the story, was discussed as being a recognizable sign of someone belonging to the bougeoise class), hires the last longtime friend he is still in contact with (Nino, played by Vincenzo Nemolato), but his new state of indifference and exhaustion turns him ugly. Like the nobles who spent their days lounging at the Palace of Versailles, he too can pull his teeth out, blackened and rotten.

On the day he is supposed to leave for the United States to promote his new book, he meets Elena for one last time and then goes to the beach, enters the water, and swims until the end credits begin rolling.

Of the shots realized with the use of a tripod, the more notable ones are those depicting Elena's letters: to avoid the stereotypical scene of Martin reading them while a voice-over tells the audience what was written, they were realized by making Jessica Cressy stand in front of a bright red wall (a color that, in the palette of the movie, seldomly appears) and look directly into the camera as she recites out loud their contents.

The way this shot is set can remind of the sorrowful scenes presented in Ingmar Bergman's Cries and Whispers, a movie from 1972 whose plot revolves around two sisters (and a maid) grieving the death of the third one. The film, whose plot is divided into four chapters, allows each of these female characters to have their own part to better display the anguish they are going through. Each part begins with a shot similar to those of Jessica Cressy reading the letters: the actress, the one whose character is going to dictate the point of view of the next part of the story, stands in front of a bright red wall and looks into the camera.

Although the story is never told from Elena's point of view, it is easy to see why Marcello would choose to be inspired by such a scene: in both movies, those moments signal the beginning of a discussion regarding death, loss, and grief, and in Martin Eden, the latter part of the plot is spent crying the identity the titular character lost.

Its titular character is initially presented as being sure of both his personhood and status: he is a hard-working sailor, his body is marred by the scars of past fights, his education level is low but functional, his wages are enough to keep him fed and clothed. In the ignorance that Elena considers to be inferior, Martin is content. It's when the status quo is shaken, that he begins drowning and loses his sense of self: those things that were normal, to his eyes, are now unfair injustices he has to oppose himself to.

As the minute count of the movie advances and the story progresses, Martin's hatred for himself grows, further cultivated by the notion that he has brought this situation upon himself for a woman who, simply, couldn't love nor understand him.

Ultimately, Martin Eden makes its audience pose questions about themselves, their position in society, and if they are willing to ask themselves questions about them both.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed