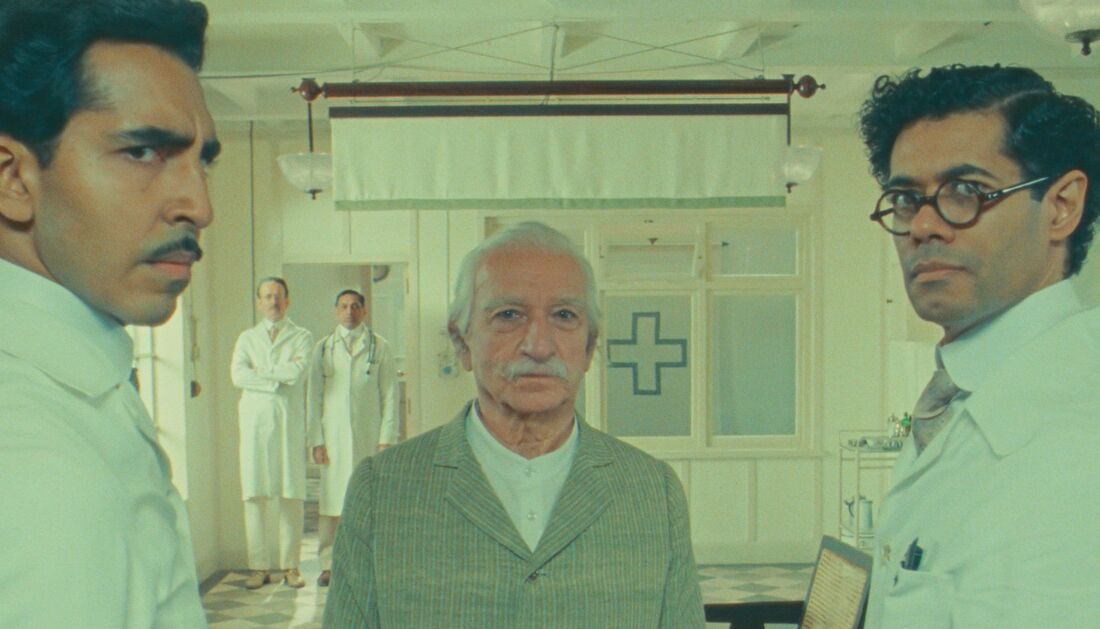

Thomas and Nolan have been married since 1997, quickly becoming one of the Industry’s most influential couples. The two often credit the success of their films to each other’s creativity and have proven themselves time and time again to be one of the driving forces of Hollywood. Their latest and greatest release, Oppenheimer, was an incredible feat of filmmaking which both Nolan and Thomas worked very hard to achieve. When asked about the making of their latest release in an interview with Variety, Thomas described it as “ the riskiest film we [Thomas and Nolan] have made.” In the interview, she touches on many of her responsibilities as a producer: casting, technical discussions, and the logistics of bringing the script to life, but also as a support system and critical opinion for Nolan, as well as a creative influence for the film. Oppenheimer was a very risky film to produce, especially with Nolan’s flare for practical effects. Thomas expressed her main concerns being the cohesion of the script, the runtime, and the mood of Nolan’s films as interpreted by audiences.

In Jimmy Kimmel’s Oscars 2024 opening speech, he remarks on the increasingly long runtimes of films this year. Along with this came a quip about Martin Scorsese's Killers of the Flower Moon in which he stated “your movies were too long this year.” Scorsese’s film has an astounding runtime of 206 minutes, almost 30 minutes longer than Oppenheimer, which still left Kimmel upset. Emma Thomas also found concern with the Oppenheimer runtime very early on in the production. Nolan and Thomas partnered with IMAX for this production to ensure the best quality possible. However, IMAX has a strict 180 minute maximum runtime for films shown in their theaters. Thomas says, “When you look at that book [American Prometheus], there wasn’t any version of this film that wasn’t going to be three hours.” Telling the story of the father of the atomic bomb is no small task, and doing it in under three hours requires incredibly detailed planning and strategic cuts by producer, Emma Thomas. Picking moments from a life as fully lived as J. Robert Oppenheimer’s is important to his accurate portrayal, and having a screenplay as successful as theirs calls back to the character and teamwork of Nolan and Thomas as a partnership. Thomas, being the practical and logistical mind and Nolan being the creative mind balance very well when it comes to pushing the boundaries of filmmaking.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed