Making a connection between Clint Eastwood and feminist theory might seem like a bit of a stretch, but the two do actually have some areas of overlap. The actor/producer/ director who gained notoriety for male-dominated Westerns and action flicks has diversified his resume, with more female-inclusive films like The Bridges of Madison County (Eastwood, 1995) Million Dollar Baby (Eastwood, 2005). A versatile, phenomenally gifted talent, Eastwood can both praise masculinity and critique it. In Gran Torino (Eastwood, 2008), he does both.

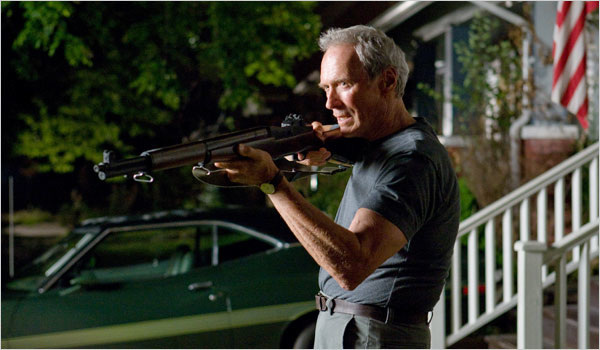

Eastwood plays Walt Kowalski, a grizzly curmudgeon, recently widowed and clinging to his spot in the "old neighborhood," even though it has moved on without him. An influx of immigrant families has turned the all-white neighborhood into a space of - in Walt's eyes - uncomfortable diversity. Walt avoids his Hmong neighbors until he catches their youngest son attempting to steal his prized possession, a 1972 Gran Torino in mint condition. Despite this initially negative event, Walt and Thao (Bee Vang) eventually build a mutually beneficial relationship.

Gran Torino has two major themes: race and masculinity. As Walt teaches Thao how to be a man, his own beliefs about manhood become evident. Walt's cultural immersion shapes the way he sees normative male behavior and gender roles, and influences much of the racially derisive language and behavior which he discards by the end of the film. Gran Torino praises positive male relationships while showcasing the negative effects of toxic masculinity.

Gender studies scholars use the term "toxic masculinity" to refer to the damaging pressures of patriarchal manhood. It speaks to the rigidity of male gender roles - which Paul Kivel calls the "Act Like a Man Box" - and the negative effects of that rigidity. Recent psychological and medical research has linked male adherence to traditional masculine gender norms with the following: loss of intimate friendships, increased rates of depression, and decreased life expectancy (Lanius & Hassel, 45). Even men who appear to fit into the " 'Act Like a Man' " box with ease are affected; they may feel anxiety about maintaining their status, or use it to police other members of their gender who deviate from social norms.

Walt exemplifies this. A physically imposing veteran with a garage full of tools, cars, and guns, he fits into the " 'Act Like a Man Box' " well, and never worries if he's not performing maleness satisfactorily. However, toxic masculinity has poisoned him. He isn't particularly proud of his time serving his country - as evidenced by the fact that he keeps all his war memorabilia, including a Silver Star medal, boxed up in the basement - and keeps his emotions strapped down under a thick sheet of anger and cynicism.

Whether intentional or unintentional, the writers behind Gran Torino make reference to another famous onscreen character trapped in the "Act Like a Man Box:" Stanley Kowalski (Marlon Brando). Eastwood's character and the A Streetcar Named Desire (Kazan, 1951 ) antagonist share a last name, a fondness for alcohol, and a history of military service - World War II for Stanley, and the Korean War for Walt. For all their similarities, the two characters differ in how they treat women. Although an unabashed racist, Walt never ventures into sexist territory, and he always targets other men with his anger and violence - never women - unlike his brutal, misogynistic counterpart.

Walt's newly forged relationships with other men counterattack the effects of toxic masculinity. Stepping into the mentor/father role for Thao requires that he release the chokehold he has had on his emotions since the war, if not from a very young age. He also learns to trust the priest who his wife confided in before her death. The positive effects of a strong social circle on Walt's life shows the importance of male friendships.

Many people work together to combat the detrimental effects of the social construction of manhood. Unfortunately, all the hard work cannot erase toxic masculinity from society instantly. Gran Torino proves that men don't just have to learn to live with its presence. Little things - like friendship - can start deprogramming damaged men trying to live up to an unattainable model.

Works Cited

Lannius, Christie, and Holly Hassel. Threshold Concepts in Women's and Gender Studies: Ways of Seeing, Thinking, and Knowing. New York: Routledge, 2015. Print.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed