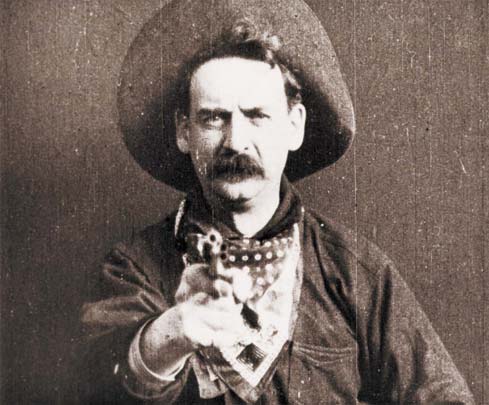

Without a doubt, even throughout its prolific era, the Western remained a flexible genre, capable of providing unique societal insights that were relevant to different time periods. During the silent era, the Western grew alongside the development of Hollywood’s studio production system and sought to capture moviegoers’ imaginations. But it was with Edwin Porter’s pioneering Western, The Great Train Robbery (1903), that the genre truly established itself as a valuable cinematic movement through the film’s utilization of innovative crosscutting editing techniques and the institution of essential conventions of typical Westerns (e.g. good guys vs. bad guys, a final showdown, a natural setting, etc).

Although the early Westerns continued to adopt a very similar style, during the 1930s, singing cowboy movies were released, which sought to highlight the musical talents of the featured actors (such as Roy Rogers), and through the 1940s and 1950s, actors like John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Gary Cooper starred in movies that idealized the cowboy as a clean-cut hero (Perry). This optimistic presentation of the Western ushered in its “golden age,” and solidified the legacies of directors like John Ford and King Vidor.

However, with films like The Searchers (Ford, 1956), the Western came to embrace the role of the anti-hero. In The Searchers, John Wayne played a racist, hate-driven loner, obsessively searching for his Comanche-kidnapped niece. Building on this darker presentation of the Western, Sergio Leone released his “spaghetti” Westerns, which brought fame to Clint Eastwood and depicted the frontier as a harsher, more violent land, void of morals and controlled by greed. With the release of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (Leone, 1968), the Western entered its “renaissance” era, where good and evil became ambiguous states. But with the release of Unforgiven (Eastwood, 1992), the genre experienced what many believed to be its swan song.

Without a doubt, the popularity of the Western as we know it has significantly diminished. In fact, some of the more recently successful Westerns are actually remakes of classics (e.g. the Coen brothers’ True Grit and James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma). Does this indicate that the Western genre is indeed dead? While it might be valid to state that the Western of the “golden age” is no more, I personally find it foolish to disregard the Western genre’s place in cinema today. With films such as No Country for Old Men (Coen Brothers, 2007), which utilizes elements of the Western to tell the cat-and-mouse story of a drug deal gone wrong, or television series like Deadwood, which takes place in a South Dakota town filled with corruption and crime, I believe that the Western has proven its evolution and can still be appreciated by modern viewers, albeit through quite a different, darker approach than at the point of its origin.

Works Cited

Perry, C.J. "The Evolution of the Western Genre." Film Slate Magazine. 6 Feb. 2014. <http://www.filmslatemagazine.com/filmmaking/the-evolution-of-the-western-genre>.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed