I’d be remiss to allow the entire month of October to pass without examining at least one Japanese horror film. This niche genre really took off with the release of Ringu (Nakata, 1998). Its captivating story of a cursed VHS tape somehow connected with audiences the world over. It made huge inroads for its genre, and even started the trend of American studios simply remaking foreign franchises as new localized releases. Throughout the early aughts, Americanized Japanese horror films became commonplace. Who doesn't remember titles like The Ring (Verbinski, 2002), The Grudge (Shimizu, 2004), Dark Water (Salles, 2005), Pulse (Sonzero, 2006), or One Missed Call (Valette, 2008)? Each of them was a direct adaptation, which many would argue lost something in the translation. Perhaps, none so much as Dark Water. And that's what I'd like to talk about tonight. So please join me as I dive into its oft underrated source material: the Japanese gem called 仄暗い水の底から From the bottom of Dark Water (Nakata, 2002).

On a purely narrative level, Dark Water shares a lot of similarities with Nakata's earlier movie: Ringu. Both tell a story about the vengeful ghost of a creepy child with long, black hair and how said ghost goes on to mercilessly torment seemingly innocent bystanders. However, unlike Ringu, Dark Water actually manages to transcend the traditional conventions of the horror genre by creating a multifaceted work of psychological horror, rife with powerful visual metaphors and an underlying message that is all too chillingly based on very real terrors. Comparing Dark Water to its predecessor is akin to likening The Shining (Kubrick, 1980) to House On Haunted Hill (Castle, 1959), as sharing a genre's themes does not equate to sharing unfathomable depth.

The plot of Dark Water follows Yoshimi Matsubara (Hitomi Kuroki), who is embroiled in an exceptionally ugly divorce and desperately fighting to maintain custody of her young daughter, Ikuko (Rio Kanno). Her estranged husband is using Yoshimi's childhood history of psychiatric treatment, received for trauma she suffered from her own parents' negligence, as evidence that she is unfit to raise their child. Short on money and desperate to forge a new life, Yoshimi moves into the shoddy Apartment 305 with her daughter, despite a small ceiling leak which the management refuses to acknowledge. The day they move in, Ikuko discovers a bright red courier bag on the roof, with the name “Mitsuko” emblazoned upon it. Yoshimi makes her daughter turn it over to the supervisor for the lost and found.

Mysteriously, the red bag soon reappears in the possession of Ikuko. Yoshimi is disturbed by this, and discards of it, only for it to reappear time and time again. Eventually, Ikuko begins to have visions of the bag's owner: Mitsuko, a soaking wet girl in a yellow raincoat. Ikuko begins to draw pictures Mitsuko in school. This causes a concerned teacher to inform Yoshimi that Mitsuko used to live in their apartment building and even attended the same school as Ikuko, but that she went missing two years earlier, while under the care of neglectful parents. This only furthers Yoshimi’s resolve to discard the bag once and for all.

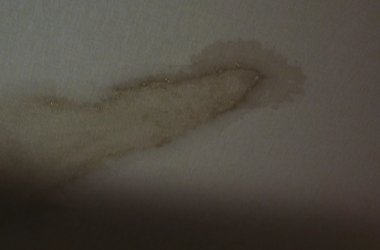

As Yoshimi’s agitation worsens, so does the leak in their ceiling. What started as a small water stain, rapidly spreads into a massive, molding expanse that begins to dribble increasingly. Within a matter of days, it looks as though a small rain shower is occurring within Apartment 305, leaving the audience to wonder what will come crashing down around Yoshimi first: her ceiling or her life.

Laura then went on to explain that in Japanese writing the character for the number four looks remarkably like the one used for death. In their culture, it is a profoundly unlucky omen. As such, there are very few buildings in Japan that technically have a fourth floor, much like American buildings omit a thirteenth floor. Armed with this information, Nakata's movie made far more sense, as its metaphors became all too clear.

Dark Water is indeed the story of people haunted by ghosts, just not necessarily the usual spooky, dead kind. No, it is very much the story of people haunted by ghosts of their past. The water dripping from Apartment 405 is a brilliant visual metaphor for the anxiety, pain and separation that progressively saturates the relationship between Yoshimi and Ikuko as the divorce proceeds. It is a growing stain upon the idyllic household that Yoshimi is desperately struggling to maintain. And the all-pervasive precipitation is a literal as well as figurative veil, representing the emotional walls dividing its characters. When Yoshimi or Ikuko looks out a window, they are looking for one another, trying to keep each other in sight. But, despite their best efforts, their gaze cannot pierce the impenetrable curtains of water.

When our protagonists finally do confront Mitsuko, the ghostly apparition of a long abandoned child, the battle of Yoshimi and Ikuko is meant to be far more internal than it may initially appear. Both see themselves in Mitsuko's soggy visage. Ikuko beholds the individual she fears she is becoming, a child neglected, left by both of her parents to die. Yoshimi sees it as a dark reflection of her own childhood, a dead, tormented thing which she has spent her entire adult life suppressing.

Rewatching Dark Water with this understanding made its ending infinitely more poignant and terrifying. To say more would spoil a chilling, atmospheric tale that brilliantly illustrates how the sins of the father (or mother) invariably result in the decay of their offspring. Even if you are not a horror fan, Dark Water is wholly worthy of your attentions. Nakata’s masterpiece drips with suspense, while flooding the screen with rich visual metaphors which will give you plenty to ponder and discuss, long after you resurface from its depths.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed