If the films from the Golden Age of female-led teen comedies (the mid-to-late 90s’ to the mid -2000s’) were a clique, Mean Girls (Waters, 2004) would be its queen bee. Even neophytes know that “on Wednesdays we wear pink.” Screenwriter Tina Fey has spoken recently about the possibility of a Mean Girls musical on Broadway. It is easily one of the most iconic teen movies of the last decade.

Mean Girls made many contributions to 2000s’entertainment- it launched Amanda Seyfried’s career and foreshadowed Tina Fey’s 30 Rock humor two years before 30 Rock even premiered – but, more than that, it spoke to audiences in a way that hadn’t been done since the The Breakfast Club (Hughes, 1985) almost two decades before – and yet did it in a way entirely different from its predecessor, spinning timeless themes into something fun and fresh for the new millennium. In his article “Mean Girls is Everything (No, Really): How One Movie Summarized a Generation,” for Complex.com, writer Julian Kimble says: “On the surface, Mean Girls is a chick flick, but it succeeds because it speaks to real people. All of them” (Kimble 1). Mean Girls’ universal nature means, like The Breakfast Club, everyone can look at Mean Girls and find a character whose experience speaks to their own. The reason for that? Mean Girls is grounded in real life – and in a way different from most teen comedies.

Not many people know that Mean Girls was based on a book…. a nonfiction book. Even less have actually read "Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and Other Realities of Adolescence.” Written by author\speaker\educator Rosalind Wiseman – a national authority on “ethical leadership, media literacy, and bullying prevention” (Wiseman 1) - as an advice guide for parents, “Queen Bees and Wannabees” has gone through two subsequent editions since its initial publication almost fifteen years ago – one in 2009, and the most recent edition in 2016. Most fans of Mean Girls are ignorant of the film’s source material, but they know its concepts. Mean Girls does a public service by disseminating Wiseman’s wisdom without preachiness, using humor to draw in young adult audiences and feeding them an important message while still giving them a good time.

Besides its source material, Mean Girls was also shaped by a classic high school film that came before: the late 80s’ black comedy Heathers (Waters, 1988). The story of two outcasts systematically slaughtering the cool kids, Heathers underperformed on its original release – unfortunate, since “with its sneaky subversiveness and disgust for its characters, Heathers is more ambitious than most high-school comedies” (Zimmerman 1). However, it is now well-regarded as a cult classic, and even inspired an off-Broadway musical.

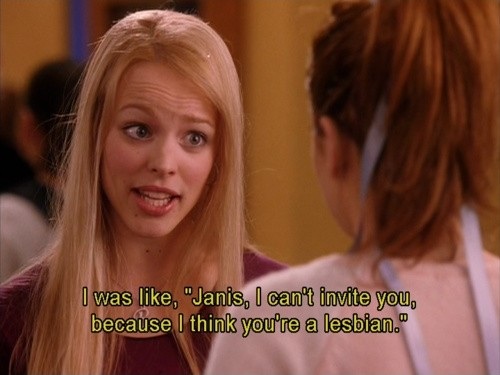

Heathers & Mean Girls are sister films – and not only because siblings helped create them. (Daniel Waters, the screenwriter behind Heathers, and Mean Girls director Mark Waters are brothers). Even without knowing the familial connection between the two films, a viewer can see the things they share. Both films are known for being quotable – although Mean Girls is more so because of its lower rating. Both Mean Girls and Heathers are ahead of their time in reference to the LGBT community and its issues. Mean Girls has the “too gay to function” Damian as one of its prominent side characters – a rarity in early 2000s’ teen films. On top of that, Cady’s first friend at North Shore High, Janis Ian, (Lizzy Caplan) used to be part of the popular crowd before Regina spread rumors that she was a lesbian.

Regina (Rachel McAdams) tells Cady (Lindsey Lohan) about Janis's fall from popularity (Mean Girls: Waters, 2004).

Heathers does not actually have any LGBT-identifying characters, but it also deals with rumors started about someone’s sexual orientation, and the consequences. Just like in Mean Girls, the subjects of the rumor can’t fight back…. not out of fear of further ostracism, but because they’re dead. After J.D. (Christian Slater) kills Ram and Kurt, he and Veronica scatter some props on the ground – as well as a forged suicide note with the line, "We realized we could never reveal our forbidden love to an uncaring and un-understanding world" – to insinuate the two were having a homosexual love affair. At the funeral, Kurt’s father stands and delivers an iconic piece of dialogue: “I love my dead gay son.” (The Heathers musical turns this touching, sobering moment into a campy, analogy-filled, musical number.) Afterwards, J.D. turns to Veronica and says, “Wonder how he'd react if his son had a limp wrist with a pulse,” turning back from sentimentality to what Heathers does so well: showcasing the unpleasant truths and bleak realities of life through humor. Mean Girls gets serious at times, too, but also still keeps audiences laughing. One similarity no one could have predicted. Both protagonists are fairly alike onscreen, but their actresses’ off-screen lives took near-identical trajectories when shoplifting arrests and substance abuse tarnished their careers.

Even though they take on many of the same issues, Mean Girls and Heathers use different worldviews to examine topical content. Cady’s inexperience with\naivete about the teenage social scene and sense of her own privilege (a quality which comes from living and working with underprivileged people groups in Africa) makes her see the world as inherently good, while Veronica, who skirts the edge of cynicism before she meets her dark prince, gets sucked into J.D.’s way of thinking: the world is inherently evil. Heathers uses shocking images and scenarios to drive its points home with viewers, while Mean Girls prefers the “iron hand in velvet glove” approach; only a few times does it directly dish out advice (e.g., when Ms. Norbury (Tina Fey) tells the girls “you’ve got to stop calling each other sluts and whores!” during the impromptu gym assembly after the release of the Burn Book.) Mean Girls keeps its comedy light, for the most part, while Heathers spends most of its running time in the darkest corners.

Many teen comedies have been released since Mean Girls, but none have reshaped the genre in the same way. Only She’s the Man (Fickman, 2006) and Easy A (Gluck, 2010) even come close. Banking on Mean Girls’ original and continued success, a TV movie spin-off (erroneously titled Mean Girls 2 (Mayron, 2011) despite having no connection to the film except for its setting) was made in 2011. The film did not perform nearly as well with audiences and critics. Mean Girls 2 tried to recreate the formula, instead of noticing what worked in Mean Girls and trying to incorporate those characteristics, as many other filmmakers chose to do. If it had emulated specific strategies, instead of attempting to make another version of Mean Girls, perhaps it would have been more successful outside of its target audience.

Mean Girls turned ten two years ago, but, overall, it doesn’t show its age. The Plastics’ fashion choices and preferred technological devices date the film, but their Burn Book, arbitrary rules about what items to wear – or not wear – on what days, and scheme of social influence feel current. The film endures because popularity, ostracism, and all of the other petty high school problems endure. Filmmakers who want to make clever and meaningful teen-oriented films should continue to look to Mean Girls as a model. The first-person narrative style is particularly effective because it allows the viewer to further identify with Cady, her experiences, and the lessons that she learns. Mean Girls may focus on teenagers, but it is, in its own unique way, intergenerational. Unless the social order or way of being drastically changes for students, I believe that Mean Girls will stay relevant for many more years, outlasting its peers in the cultural consciousness.

Works Cited

Kimble, Julian. “Mean Girls is Everything (No, Really): How One Movie Summarized a Generation.” Complex. 30 April 2014, http://www.complex.com/pop-culture/2014/04/mean-girls-the-movie-of-the-millennial-generation. Accessed 20 September 2016

Wiseman, Rosalind. “About Rosalind.” Cultures of Dignity, http://culturesofdignity.com/about-rosalind/. Accessed 22 September 2016

Zimmerman, Alan. “So Very, 25 Years Later: The Bleak Genius of Heathers.” The Atlantic. 31 March 2014. http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/03/still-very-25-years-later-the-bleak-genius-of-em-heathers-em/359828/ Accessed 20 September 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed