By Bill Friedell

| | |

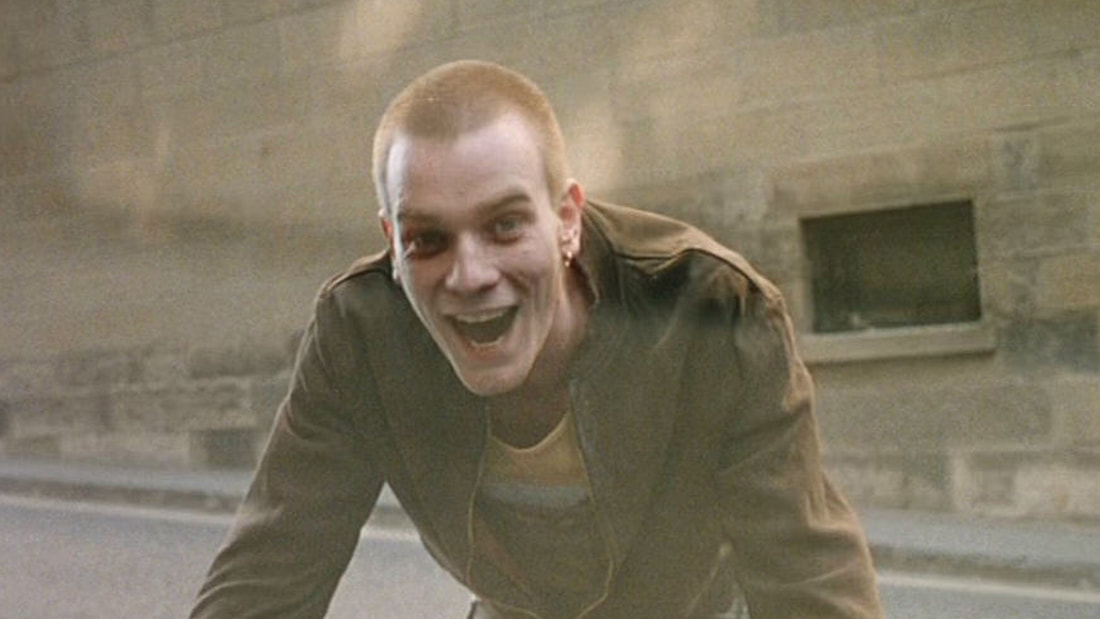

One scene that encapsulates Renton’s view of the past and how it relates to the present is through a direct reference and update on the “choose life” monologue (Trainspotting: left, T2: Trainspotting: right) that opened the original movie. Renton explains to Veronika (Anjela Nedyalkova), Sick Boy’s girlfriend and business associate, what “choose life” means. Originally an antidrug slogan, Renton and Sick Boy appropriated it and turned it into a joke. At first it seems silly enough. Even the beginning of “Lust for Life” plays with the lighter hearted parts of the monologue, referencing “designer lingerie, designer shoes” and Facebook and Snapchat posts meant to “spew your bile to people you’ve never met”. But then it gets darker with each new spin Renton puts on it, culminating in him revealing his dissatisfaction with not only the world, but himself. We see Renton in an empty bed, a reference to his upcoming divorce. We see his grief over the loss of his mother mirroring a shot seen when Renton first returns home; it is the exact composition of the shot without her from earlier in the film, except his mother is there and Renton is young, fresh from Trainspotting.

This allows us to feel what Renton was experiencing from his point of view, at least from someone who has seen Trainspotting. The next thirty years he will supposedly have after his surgery seem like a nightmare and existential crisis to him because he sees that the twenty years away from his old life as a heroin addict were just as wasted as the time he spent clean. We get a true glimpse of what he has experienced since we last saw him and get greater context to the scene previous. People who had not seen the first movie would probably identify with Veronika, the new person POV who is listening to a forty-something year old man pour out his misery and regret.

Renton sees no other alternative or direction to go, so he instead leans back to the time and people he felt most alive with, stating, “he can’t think of doing anything better”. A study was conducted on nostalgia at the University of South Hampton defines nostalgia as such: “Nostalgia is about close others (family members, friends, partners), momentous events (birthdays, anniversaries, vacations), and settings (sunsets, lakes). It is a self-relevant emotion (as the self is invariably the central character in the narratives) but also a social emotion (as the self is almost always surrounded by close others). It is also bittersweet, albeit mostly positive. And it is triggered typically by aversive conditions, such as negative affect or loneliness” (Tierney).

This idea is bought into a particularly harsh light at a train station out in the green where Renton, Sick Boy, and Spud, were dragged to in the first film by their friend Tommy (clip above). They are there in memoriam to Tommy, who died in the first movie. There’s duality in the nostalgia. There is legitimate joy. But there is a distance that Sick Boy even comments on: “Nostalgia. You’re a tourist to your youth. Just cuz you had a near death experience that left you feeling warm and fuzzy. What other moments will you be visiting?”. It’s his selective memory that seems to be part of Renton’s problem. He wants to remember the good times but has yet to make peace with the not-so-fuzzy parts. Renton got their belated friend Tommy hooked on heroin, who eventually died young because of it.

Throughout the film, it is clear to Renton and the audiences that none of the characters Renton left behind have changed (at least not in too meaningful a way). Spud is still a junkie despite having an ex-lover and child. Begbie may be out of jail (broken out) with a son with good prospects, but is still a raging, foul-mouthed, violent man who couldn’t be more petty and willing to drag his son down the same path he took himself. Simon (Sick Boy) is still getting into trouble with the law, despite getting a partner in crime (Veronika), and has graduated from heroin to cocaine. They are stuck in a cycle. And so is Renton. He has come back and now wishes to participate in Sick Boy’s newest hair-brained scheme. He has nothing better to do with his next thirty years.

What sequels from years later forget is that references need to have purpose. It’s easy to get an emotional reaction out of telling the audience to remember what the original did. This movie knows it cannot recapture the glory days of 1996. So, it leans on tackling the past and realizing that Renton needed to return to this structure in order to break these characters, and himself, out of their destructive cycle. The journey of Renton in T2: Trainspotting is the story of a man confronting his past and learning to both embrace it and move forward. Nostalgia can be a source of healing and closure.

Works Cited

T2 Trainspotting. Dir. Danny Boyle. Sony Pictures Entertainment, 2017. DVD.

Trainspotting. Dir. Danny Boyle. Polygram Filmed Entertainment, 1996. DVD.

"Nostalgia Group Members ." Index | University of Southampton. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2018.

Tierney, John. "What Is Nostalgia Good For? Quite a Bit, Research Shows." The New York Times. The New York Times, 08 July 2013. Web. 25 Feb. 2018.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed