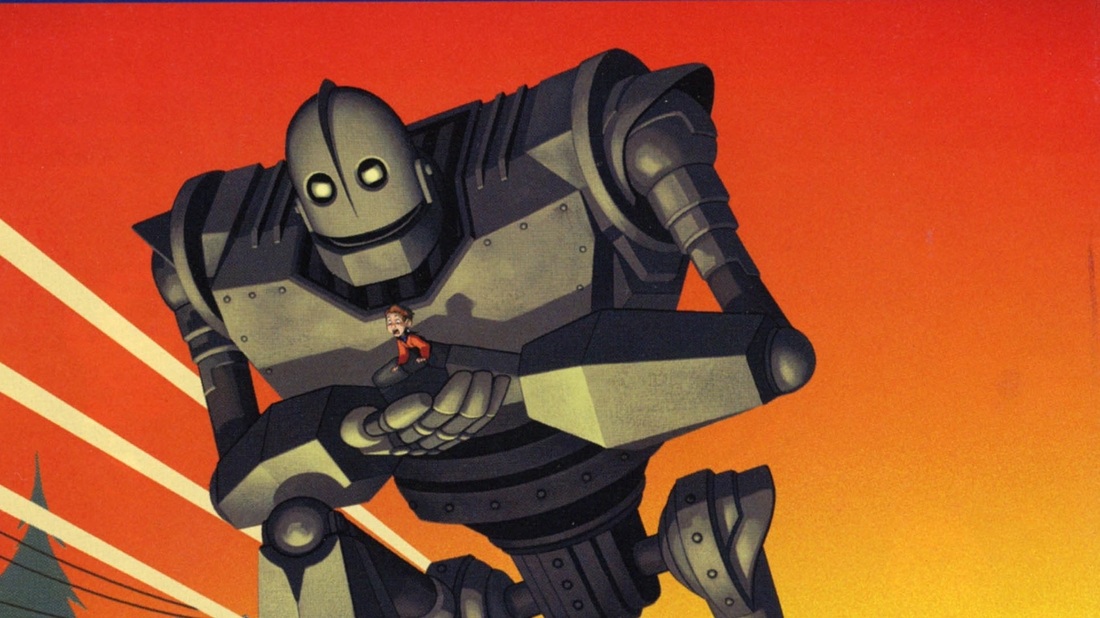

The film centers on 9-year-old Hogarth (Eli Marienthal) a loner kid who has no trouble passing time in the coastal town of Rockwell, Maine, as imaginative boys do. He and his mother (a war widow, voiced by Jennifer Aniston) live a quiet, private life together in 1957 until a giant iron "man" falls from the sky and Hogarth adopts him as his friend; he knows that the giant needs to remain a secret and hides him in his mother's barn. The giant, you see, is a weapon, though rendered inert via a dent on his head. In a heartfelt scene about identity, Hogarth reads comics-as-bedtime stories to the giant; he likes "Su-per-man" but becomes distressed when he sees a cover featuring a violent robot. Hogarth's earnest reassurance -- " you can be who you choose to be" -- becomes the emotional touchstone of the film, even echoing through supporting characters like Mansley (Christopher McDonald) and Dean (Harry Connick, Jr. in my favorite thing he has ever done).

Neither Mansley nor Dean existed in the book the film is based on, The Iron Man by Ted Hughes. I haven't read the book, but the film's narrative benefitted from their inclusion so much that I cannot imagine the story without them. Hogarth's unlikely friendship with Dean -- a beatnik metal-working artist whose "live and let live" philosophies contrast nicely with the unrelenting tension of the outside world -- provides emotional respite for our heroes and the audience alike. After a reluctant start to their relationship, the pair find a rhythm of easy understanding that illustrates people's ability to connect through shared values despite being very different in all other respects. Housing the giant in Dean's junk yard lent itself to comedic moments as well as some of the best character development of the story; it is here that The Iron Giant's intelligence shines. Through Dean and Hogarth's interactions, mutual trust and respect push them both to make braver choices than would make on their own. Mansley, on the other hand, is Hogarth's immediate enemy: driven, singular, and reckless in his desire to "protect America at all costs." He sees people in black and white terms; forgets the possibility of innocence; has forgotten his own boyhood. Yet, Mansley is not the villain; he is a representation of what happens when people allow themselves to be primarily motivated by fear.

About the Cold War setting Roger Ebert commented, "The movie is set in the 1950s because that's the decade when science fiction seemed most preoccupied with nuclear holocaust and invaders from outer space." The heightened sense of paranoia that was so pervasive at the time is the true villain of the film: unseen, lurking, oppressive. From classroom bomb shelter drills to Russia's Sputnik orbiting overhead, each individual citizen was acutely aware that times were tenuous at best. It was not unreasonable to be afraid. The emotional climax of the story, however, insists that peace is the harder, better goal; and as we see through Mansley's desperate actions, warfare is the coward's realm.

Is this a kid's movie? Yes. It has enough charm and relatability in Hogarth that kids will not feel condescended to; there are plenty of visual gags and impressive action sequences; and the giant himself -- well... he's pretty cool.

But is this just a kid's movie? Not at all. Refreshing stillness emanates from the straight-narrative format (versus musical numbers and splashy CGI animation). At one point in the film, Hogarth "suits up" with his army helmet and BB gun, ready to serve his country, and salutes himself in the mirror with all the intensity of a decorated vet; but he is just a boy with no concept of warfare. Despite it claiming his father's life, Hogarth still wholeheartedly emulates his country. The contrast of boyhood hero idolization with messy real-world politics is simply irrelevant when faced with Hogarth's determination, and it is this kind of understated moment that elevates The Iron Giant beyond typical animated fare. Brad Bird and Tim McCanlies were prescient with their message that global community may trump old-fashioned nationalism, but it doesn't have to be at the expense of patriotism. The message continues to be poignant in our post-9/11 world -- a fact which might explain the film's cult status.

Or, it could just be that good.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed