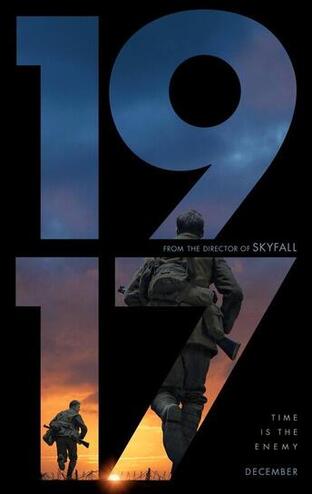

1917 is the story of two British soldiers in World War 1 who are selected for a dangerous mission, in a race against time to save over 1,000 lives. This journey takes them through the No-Man’s Land of the trenches, all the way into enemy territory. The two soldiers, played by Dean-Charles Chapman and George MacKay, are forced to rely on each other to survive in order to accomplish their mission in the short amount of time they have.

Immanuel Kant, an eighteenth century philosopher, wrote about an experience which he called the “dynamically sublime”. The dynamically sublime was a sense of sublimity caused by an overwhelming danger, which brought about bravery in mankind. The juxtaposition of this great danger and this great bravery is what caused the sense of the sublime. One particular source of this sense of the sublime, according to Kant, could come from war. War, Kant wrote, “has something sublime about it… only the more sublime the more numerous the dangers to which they are exposed, and which they are able to meet with fortitude” (Kant, 93). I believe that 1917 captures this sense of the sublimity of the bravery which it takes to sacrifice oneself in war. The climax of the film, which involves a massive charge of troops, with a main character taking a major risk to accomplish his mission, is monstrously sublime. In the theater it felt almost overwhelming.

Not much more can be said about 1917. It is both a technical and artistic masterpiece, and is one of the best films of the year. In a year which has been full of excellent films, 1917 will stand out. I would not be surprised to see 1917 win the Oscar for Best Picture this year. It also will not be much of a surprise if Deakins were to win yet another Best Cinematography award, although I personally am rooting for The Lighthouse for Best Cinematography.

For more information on how 1917 was filmed, see here:

KANT, IMMANUEL. CRITIQUE OF JUDGEMENT. A & D Publishing, 2018.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed