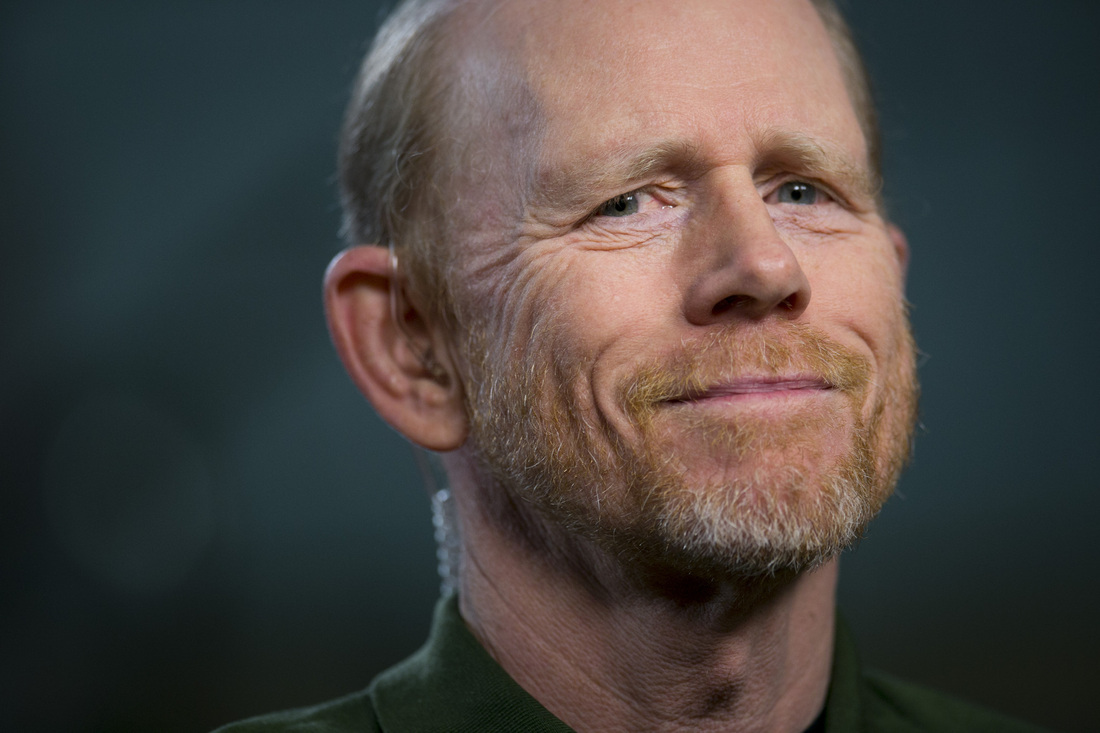

Howard was put into the film business at an extremely early age, as his first screen appearance came in Frontier Woman (Ron Ormond, 1956) when he was just 18 months old. Furthermore, his first theatre experience came in a production of The Seven Year Itch when he was merely 2 years old. From here, he began to make several appearances in television shows. Following these appearances, Howard soon made an appearance in his first feature film, The Journey (Anatole Litvak, 1959), starring opposite Yul Brynner, Deborah Kerr, and Jason Robards. For his strong performance in the film, Howard was soon approached by several producers, and earned a regular role in the TV series Playhouse 90 (Biography). Importantly, it was during this time that his father closely monitored him to prevent exploitation by directors, as his presence as a child actor was rapidly growing. Howard was given confidence while acting in that his father always made time to be on set with him (Fandango).

Howard gained much attention for these early roles; however, it was the role of Opie Taylor on The Andy Griffith Show that really jumpstarted his career. Playing Andy Griffith’s six year old mischievous but adorable and lovable son, Howard gained fame across the nation as a talented child actor. His parents, and in particular his father, closely monitored Howard’s shooting schedule and ensured that he still had a productive and authentic childhood. His father also insisted he get a good education, and placed Howard in public school (Biography).

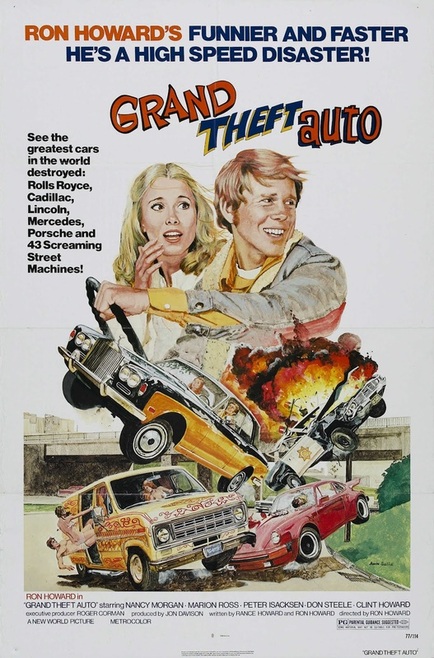

Directorial Debut

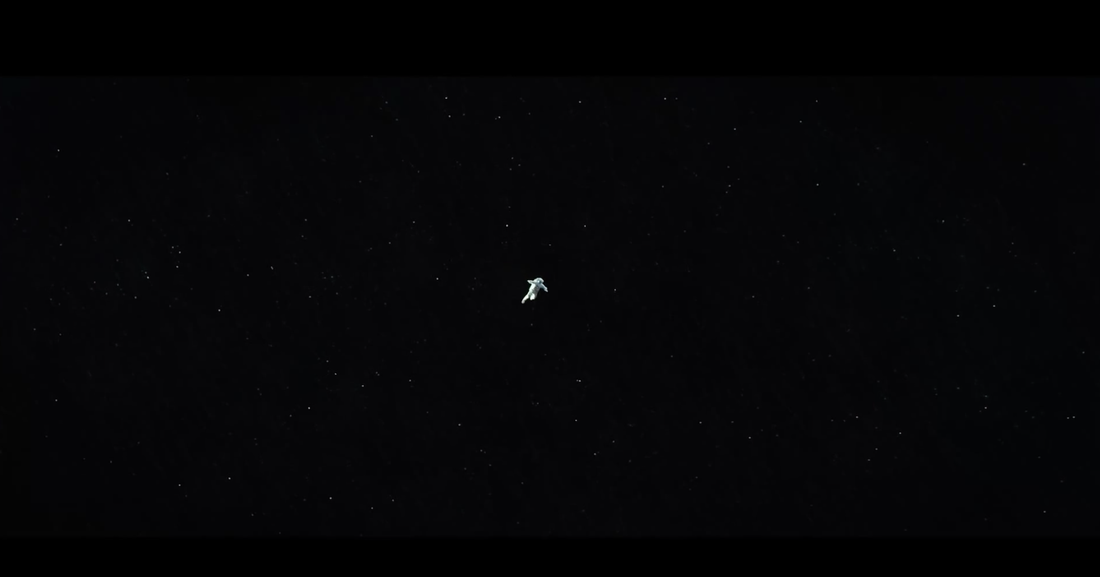

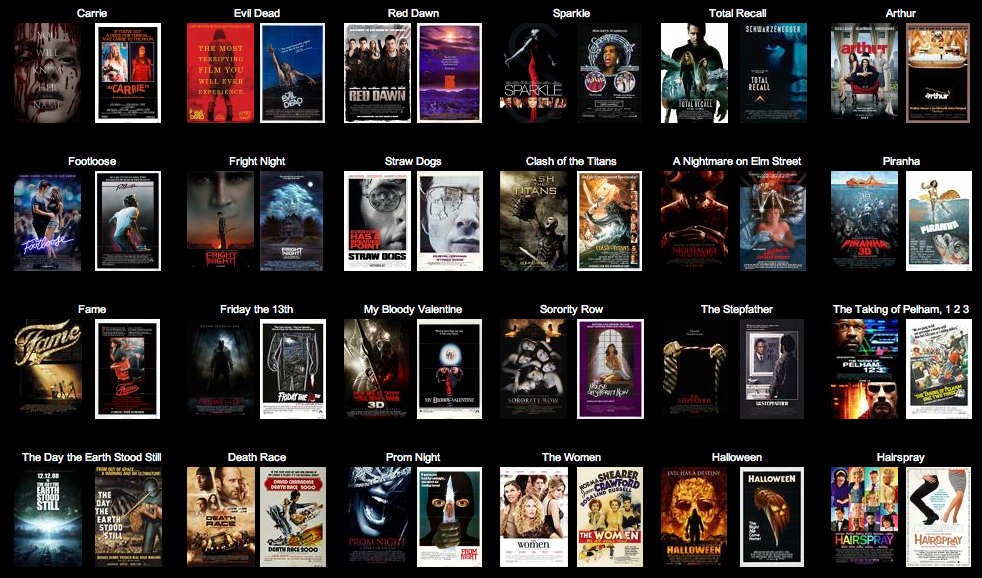

In 1985, Howard founded a production company, Imagine Films Entertainment, with his recent producer Grazer. He would use this company to produce several of his films in the ‘90’s, including Backdraft (1991), Apollo 13 (1995), and Ransom (1996). Apollo 13 was an international smash hit detailing the failed and nearly disastrous 1970 mission to the moon. The film reunited Howard with Tom Hanks, and the film garnered 9 Oscar nominations, winning 2 for Best Sound and Best Film Editing. For the film, Howard also received the prized Director’s Guild Award (Fandango).

After A Beautiful Mind, Howard continued to produce critically and commercially successful films, including Cinderalla Man (2005) and The Da Vinci Code (2006). In 2008, he directed Frost/Nixon, for which he received an Oscar nomination for Best Achievement in Directing, and in 2009 he directed The Da Vinci Code’s sequel Angels and Demons. Most recently, he directed Rush (2013), a film starring Chris Hemsworth detailing the intense rivalry between British and Austrian racers James Hunt and Niki Lauda. He is currently in post-production on In the Heart of the Sea, which tells the true story of the 1820 whaling ship incident that left the crew adrift for 90 days.

Today, Howard remains married to his high school sweetheart Cheryl, whom he married in 1975 during his run on Happy Days. They have 4 children together.

Trademarks

Other trademarks include people he works with: he typically hires James Horner to compose his film scores (Cocoon, Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind) and typically casts A-list actors, including Tom Hanks (Apollo 13, The Da Vinci Code, Angels and Demons) and Russell Crowe (A Beautiful Mind, Cinderella Man). Finally, he typically casts his father Rance Howard (Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind) and brother Clint Howard (Apollo 13, How the Grinch Stole Christmas) in supporting roles.

Works Cited

Perno, G.S. “Director’s Trademarks: Ron Howard.” Cinelinx. 2013. 26 Oct. 2014. <http://www.cinelinx.com/movie-stuff/item/4661-directors-trademarks-ron-howard.html>.

“Ron Howard.” The Biography Channel. 2014. 26 Oct. 2014. <http://www.biography.com/people/ron-howard-9542185#synopsis>.

“Ron Howard Biography.” Fandango. 2014. 26 Oct. 2014. <http://www.fandango.com/ronhoward/biography/P94983>.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed