Presentation and Representation: The Affective Use of Art in Nocturnal AnimalsBy Angelina Leong Art itself cannot be reproduced completely. Certainly, each brushstroke can imitate the original, and every shade can be the same, but at its very core, the difference between original and counterfeit is significant in its meaning. Beneath a veneer of paint lies a truth fully believed and conveyed by the artist that is impossible to receive and reproduce, as no philosophical truth can ever be entirely duplicated. However, art itself can become a secondary or even tertiary layer beneath which another artist might conceal yet another meaning – and this is what Tom Ford does with his use of art in Nocturnal Animals. The works of art accentuate the suppressed underlying mental space in which Susan gradually regains over the course of the film, and further allow the audience to perceive how she is affected by the beauty in art around her. As such, this essay looks at how art is presented in Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals, and further argues that each work places an emphasis upon the affective effect for both Ford’s audience and protagonist.

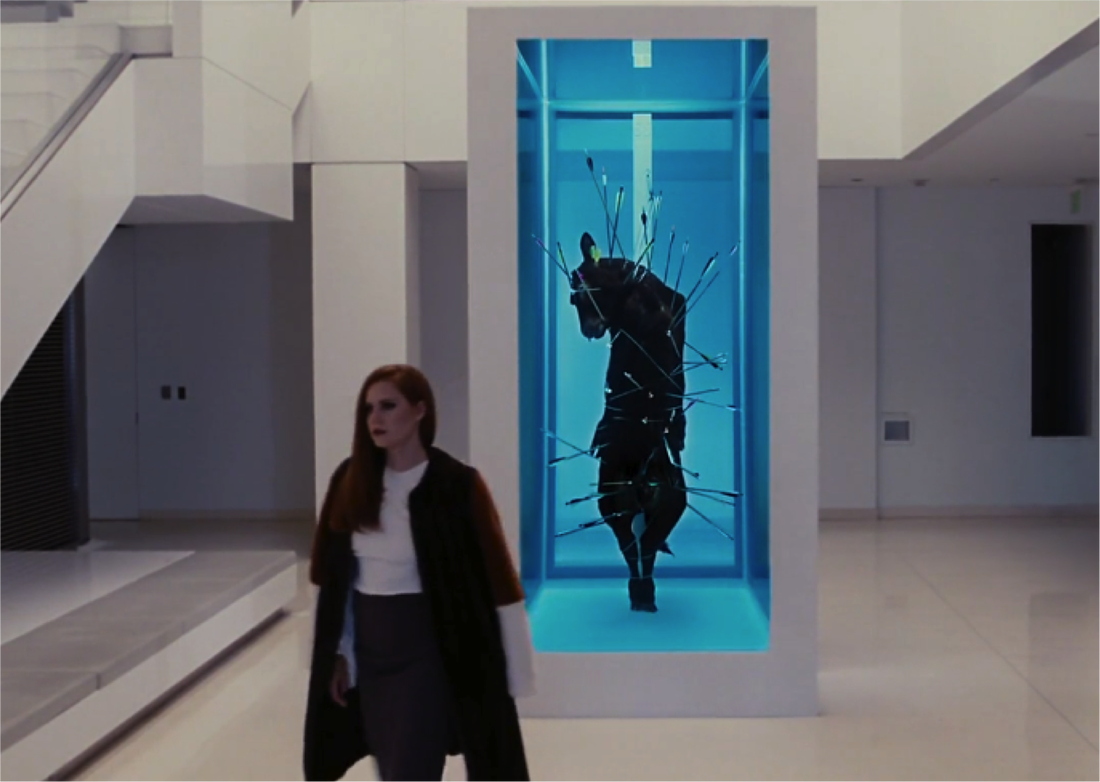

Plato once defined art as imitation, and sought to remove art from his ideal society “on the grounds that art was of minimal practical use” (Danto ix). Others, like Leo Tolstoy, understood it as a contradiction even within “its own devotees” to the point where “it is difficult to say what is meant by art” (What Is Art?). Some even see art as an existential medium: “Art is less involved in making sense of the world and more involved in exploring the possibilities of being, of becoming, in the world” (O’Sullivan) – that is to say, art in itself becomes a creature made at the hands of humanity to both portray and evoke thoughts behind its surface, allowing its audience to become absorbed in a created world. To this day, different schools of thought boast distinct understandings of the same term with little chance of total agreement. However, the traditional understanding for art stems from an experience of pleasure in the visual form – in sculpture or painting, or more broadly: the fine arts. Art, then, becomes that of enjoyment for a piece claiming beauty and elegance in its form – but the question remains for the constitution of art itself. In order to fully acknowledge and assess the effective use of art within Nocturnal Animals, it is necessary to look at all potential forms of art – after all, “if we exclude from the domain of art all that to which the critics of various schools themselves deny the title, there is scarcely any art left” (What Is Art?). Thus, for the purposes of the essay, the definition of art used is simply that of all aspects of creativity expressed through Nocturnal Animals: from novels, to paintings and installations, to the audio-visual medium through which the film is expressed. Ford introduces the idea of Susan’s constricted inner self and promotes the lack of enthusiasm she portrays in the ‘reality’ half of his film through the intelligent placement of art throughout Nocturnal Animals. As the entirety of Edward’s novel takes place, ostensibly, in Susan’s head, it is undoubtedly not coincidental that “the house Tony walks up to from the highway after his family was taken from him looks like a John Divola photo, or the standoff between Ray and Tony at the end looks like a Richard Misrach photo” (qtd in Prudowska) – these very pieces are found throughout Susan and Hutton’s household, underlining the differences and similarities between reality and fiction. Susan’s only perception of West Texas is that of the high society’s understanding that plays into the stereotype of a wild, dark and dangerous west, and this is how – in essence – the setting of the novel is presented in her mind. Thus, the art in Nocturnal Animals becomes entirely a representation of Susan’s inner self. This is further explored in Susan’s own character: like the pop culture figures that Shaviro considers in his Post-Cinematic Affect, Susan attempts for the dignity of “idealized stillness, solidity, and [the] perfection of form” that art itself possesses through acting the part of a demure, loving trophy wife in society. Having been curated by the materialistic culture, she is often depicted in stillness itself – such as in the opening sequence with her resting on the edge of the installation, or in her own office where movement is minimal. In the cases where she attempts to move too much or too quickly, she becomes hurt – as evidenced in her inability to rip open Edward’s package without receiving a paper cut. This is all despite her apparent distaste for the life she lives: “Do you ever feel as though your life has turned into something you never intended?” (Nocturnal Animals). The art, however, is curated to preserve its own naked truth: its vivid depictions of life in a mixture of bright and dull colors both, expressing beauty and a sense of liveliness that Susan lacks. There is an ironic dichotomy in the presentation of famous paintings and the diminutive, highly reserved manner that Susan presents herself – the naked woman installation that opens Nocturnal Animals depict an enthusiasm and confidence that Susan noticeably lacks. Where Susan constrains herself within the high society of the arts, these women as fine art have “let go of what […] culture […] said [they are] supposed to be” (qtd in Buchanan). This is significant to Susan’s inner self, as the women themselves represent what she could have been had she fought off society’s expectations and stayed with Edward more than a decade ago. Another example for Susan’s inner self represented in art belongs to John Currin’s Nude in Convex Mirror, which exhibits the rump of a lady in a convex mirror as a stark contrast to Susan’s own repressed, minimalistic and demure self. In the scene of Susan’s office, both character and painting encompass up opposite corners of the screen in the shot, with Susan in the bottom right half and Nude in the top left. The difference in the painting’s exposure and Susan’s modesty of dressing becomes obvious in the framing of the shot, and certainly conveys how art becomes the visual representation of the woman Susan desires to be: confident, happy and in love with life. In the film, art becomes crucial not only for “reflecting [the] inner world of the main character, but also [to] expand the storytelling” (Prudowska), intending to evoke emotion in the same way that Susan attempts to placate the people around her – by claiming her health to her friends, in her desire to rekindle the romance between Hutton and herself, and further in acting as the perfect significant other for the business-minded husband. “I’m being summoned. Pardon me” (Nocturnal Animals). While some of the art in the film represents Susan’s mental state, others still are a commentary upon her life and a critique of her emotional lack. Shane Valentino explains that “when Susan pauses in front of Damien Hirst’s sculpture, St. Sebastian, Exquisite Pain, the piece reveals how one’s vulnerability allows one to behold beauty. It feels like it is exposing her previous avoidance of love and its grim consequence” (qtd in Prudowska). Hirst’s sculpture becomes an externalization of her mental state, and the audience is immediately presented with a mental image of Susan herself standing in place of the stuffed animal, held up stiffly with the sharp instruments piercing of societal expectation through her body. This is all done in sacrifice for her own well-being: in constantly repressing her emotions, Susan possesses an alarming incapacity for empathy and care – not only for the creative field that she once sought to dive headfirst into but now detests, but also for the people she claimed to love. The latter is evidenced in her divorce with Edward and the abortion of their child, she having done so in the wake of her frustration with his literary aspirations and his inability to provide for the materialistic life that both she and her outspoken, domineering mother desired. The art becomes not only a physical representation of the side of Susan that Ford’s audience does not see in her character, but also a means through which viewers understand her past.

Art “demands such tremendous labor-sacrifices from the people, which stunts human lives and transgresses against human love” (What Is Art?); yet, it becomes ultimately fulfilling to a creator who has lost all else, especially when its results allow one to resolve a prior issue – like the abandonment of one’s wife for another man, and the abortion of one’s child in the process. Representative of the wildly emotional part of her subdued inner self, Edward uses his novel to provide sense of catharsis for his heartbreak: “after Susan destroyed Edward's heart, he used that pain – transmuting the very common and mundane acts of infidelity and divorce that happened in NYC into a thrilling revenge narrative set in West Texas. That's the inspiring role emotion plays in creating art” (Lambert, emphasis mine). The rawness of his work certainly stands out against the prosaic background of Susan’s life, and is further used to incite a form of petty revenge against her. Edward’s romanticism has given him strength to write a heartbreakingly beautiful piece that is, in essence, raw and uncontained art with no boundaries – to the point where it actually takes over the narrative in the film. Conversely, having abandoned her dream to become an artist for being too cynical-minded, and instead entering the bland commercial world, Susan completely loses sight of beauty – and as such loses the drive to live a meaningful life. Knowing this, Edward exposes his vulnerability, which draws her in, and dangles the hope of returning to where they were only to leave her waiting with no end. This form of revenge is starkly different from the visceral portrayal of anger, bitterness and hurt found in Tony’s actions against Ray; much like Hirst’s sculpture, the novel is able to become a near-tangible depiction of revenge, exhibiting the inner perception of perfect retribution against another. Shaviro suggests that, in entertainment, the audience is often offered “more than [entertainment] delivers, enticing us with a ‘promise of happiness’ that is never fulfilled”. To this end, reality reveals that revenge is not quite so dark: Edward’s revenge, unlike Tony, can only be to show Susan what it feels like to be left alone by one who once cared for her. “In the realm of the virtual, art […] is […] not only an object, but rather a space, a zone or what Alain Badiou might call an ‘event site’: ‘ a point of exile where it is possible that something, finally, might happen’” (O’Sullivan). Edward, then, has essentially taken action against Susan through the creation of his art by making its premise Badiou’s ‘event site’ – his devastation at Susan’s leaving inspires him to purge the anger through the novel and thus allow him to move on from that period of their life while dropping Susan in the same place he just vacated. Film scholars Carl Plantinga and Greg Smith have noted that people view a film – and other forms of art – in order to feel (Podalsky 3). With a wide variety of art, Nocturnal Animals does not disappoint its viewers: Ford’s representation of revenge on screen, played within the growing imagination of Susan herself, catches the audience’s attention and thus evokes an emotional response – similar to how the novel evokes a response in Susan to reach out and contact Edward in order to perhaps reconcile their differences. As such, audience and character both become a spectator to Edward’s art, drawing both closer as they observe the events unfolding in novel, or on screen. “By having the novel-within-a-movie it makes Susan's and Edward's ‘reality’ seem closer to our own, and Tony's all the more distant” (Lambert). As Susan begins to identify with Tony as she takes in the devastation of his life – to the point where she expresses concern for her daughter after reading about India’s death – the audience identifies with her identification (quite recursively) through their identification with Susan herself. Carl Plantinga notes that there are two “broad types” of spectator emotions – “those identical with the emotions of the protagonist and those ‘which may be entirely different, perhaps exactly opposite to those which the figures play in express’, and which stem from the spectator’s ‘independent affective life’” (qtd in 13-14). The audience thus appears to co-exist within Susan’s mindscape, ‘reading’ and collectively getting in touch with Susan’s inner self alongside her. One could argue that this is prompted by the occurrences on screen: “throughout our viewing of a film we are generally in some emotional state or other” (Plantinga 23), modulated by the film itself. The more human the audience, the more capable of possessing emotions, the more an artwork’s audience becomes able to be affected by what they read, see, or even hear. Ford ensures, with the story-within-a-story technique, that this can only be done through Susan. Psychologist Torben Grodal suggests that affective reactions are only possible when there is a successful “construction of objects” to incite a series of mental processes that create a “mental representation of what is seen and heard. This in turn induces affective reactions” (Plantinga 132). In creating a focus for the audience by juxtaposing works of art with Susan herself on screen, Ford demands his audience be drawn further into the world he depicts through film. Henri Bergeson defines attention as the “suspension of normal motor activity which in itself allows other ‘planes’ of reality to be perceivable” (O’Sullivan) – that is to say, by paying attention to a work of art, the audience becomes more easily swayed into believing the portrayed reality, such as the meaningless high society premise of Nocturnal Animals.

Art has certainly been a force of affect throughout Nocturnal Animals, first in the audience’s relation to Susan and also in Susan’s relation to Tony in the novel. The more viewers pay attention to a character, the closer they feel to that character, thus drawing their once-distinct emotional stream together and the audience into the world of the film or art. Perhaps the longer we stand looking at a work, or the more we read or view a novel or a film, the closer we become to the world of art – and thus the closer we become to not simply understanding the world, but being. Works Cited: Asheim, Lester. “The Affective Film”. Journal of the University Film Producers Association, 8.1 (1955): 4-9. JSTOR. Web. Buchanan, Kyle. "Tom Ford Explains the Controversial Opening Credits of Nocturnal Animals." Vulture. New York Media, 13 Sept. 2016. Web. 25 Apr. 2017. Danto, Arthur C. What Art Is. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2013. Google Books. Google. Web. 19 Mar. 2013. Lambert, Chris. Explaining the end of Nocturnal Animals: why Edward didn't show up, why this is existential revenge, and why Susan is doomed. 21 November 2016. 16 April 2017. Nocturnal Animals. Dir. Tom Ford. Perf. Amy Adams, Jake Gyllenhaal, Michael Shannon. Focus Features, 2016. DVD. O'Sullivan, Simon. "The Aesthetics of Affect: Thinking Art beyond Representation." Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities. 6.3 (2001): 25-35. Web. Shaviro, Steven. "2.2 Post-Cinematic Affect." Post Cinema: Theorizing 21st Century Film. Ed. Shane Denson and Julia Leyda. U of Sussex, UK: Reframe, 2016. Reframe, 11 Apr. 2016. Web. 16 Apr. 2017. Plantinga, Carl R, and Greg M. Smith. Passionate Views: Film, Cognition, and Emotion. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. Print. Podalsky, Laura. The Politics of Affect and Emotion in Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, and Mexico. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print. Prudowska, Mirra. “Nocturnal Animals: How Contemporary Art Plays Its Own Role." WM Daily. Welker Media, 23 Jan. 2017. Web. 12 May 2017. Rosenthal, Emerson. "Everything We Know About the Art in 'Nocturnal Animals'." Creators. Vice, 11 Jan. 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017. Tolstoy, Leo. What Is Art? Leo Tolstoy, 2016. Google Books. Google, 8 Jan. 2016. Web. |