There Won't Be Many Coming Home: Masculinity and Violence in Hateful EightBy Brandon Gordon Each society has its own idealized version of what it means to be a man. He may be strong and brooding, suave and sexy, or kind and compassionate. In American society during the 1950’s and into the 1960’s the ideal man was seen as strong, steadfast, and heroic. This classic figure was usually epitomized in western films of the time. Little has changed over the perception of the ideal man in America, only the genre in which he exists has grown to include more action and fantasy driven films that reach a wider audience. This growth has not changed the classic idea that a real man is strong and brave, especially in the films of Quentin Tarantino. Since his career began over twenty years ago Tarantino has reminded of us of the harsh masculinity and inclination toward extreme violence that can at times be associated with it. Since his early work of Reservoir Dogs (Tarantino, 1992) and Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994) we have seen how he shapes his movies around the violent spectacle and those who create it. Tarantino’s most recent film revisits these themes of violence and masculinity. Hateful Eight was released in late 2015 and quickly reminded why Tarantino is the ruling king of combining machismo and violence in a highly spectacular way. Set against a backdrop of a classic western Tarantino takes the viewer on a trip exploring each characters inclination toward violence and being the alpha male of the pack.

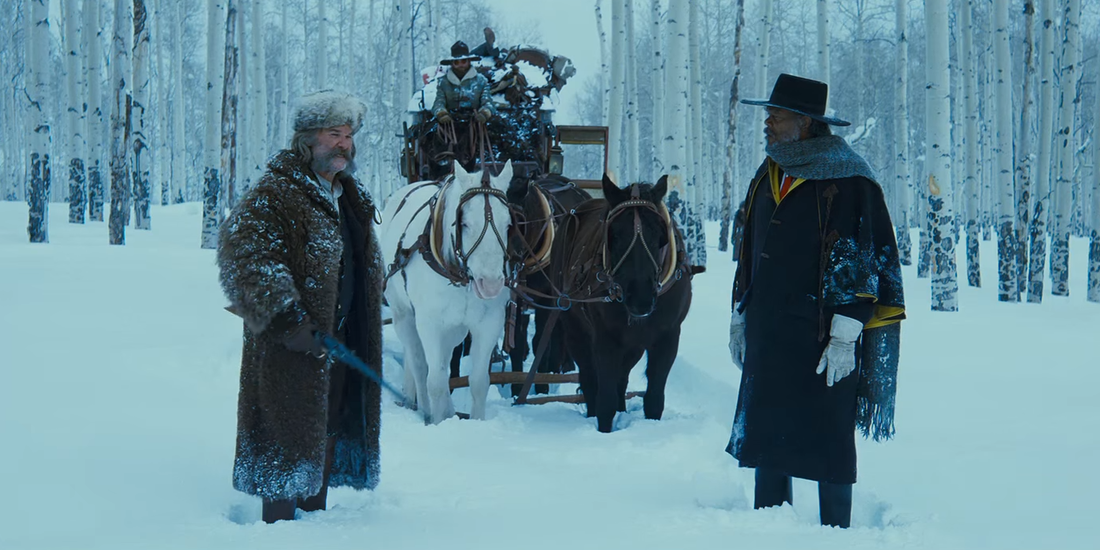

In order to understand Hateful Eight it is important to understand the work of Tarantino as a whole. His films are distinguishable and have quickly acquired the name brand that draws many film aficionados to the theater. There is a clear style that has developed these films. Many have come to recognize the writing as one of the clearest signifiers of a Tarantino film. The dialogue is unlike most other films, as it does not need to focus on the plot of the film but rather the characters within the film. It is not uncommon to have sequences in a Tarantino film in which several characters may be talking about something that has nothing to do with the story that is unraveling before the viewer. It is in these conversations that we learn more about the character than we would through traditional dialogue that one expects to see in a film. The opening scene of Hateful has Major Marquis Warren (played by Samuel L. Jackson) catching a ride on a carriage with John ‘The Hangman” Ruth (played by Kurt Russell). In this sequence, we see the two sharing about how they each arrived at this point in Wyoming in the middle of a snowstorm. It is during this time that we meet Daisy Domergue (played by Jennifer Jason Leigh), a criminal with a bounty on her head being delivered to the town of Red Rock by John Ruth. The three engage in conversation that slowly divulges character information in a subtle way that catches the viewer off guard. This is the Tarantino style that has been used in each of his films. As far back as Reservoir Dogs, which starts with a conversation about Madonna, Tarantino has an uncanny way of telling so much from a conversation about nothing. What is notable is that these are the conversations that people have everyday. It is uncommon for us to see a full conversation in a film that one could have on any given day, but this is the style that audiences have come to expect from Tarantino. This form of dialogue has a very important role to play within Hateful Eight. At its core, Hateful Eight is a murder mystery wrapped in a Western focusing on a group of people with violent pasts being trapped together with disastrous outcomes. Dialogue is crucial to the film within a setting such as this. There is so little going on within the cabin other than the conversation between the characters that dialogue becomes the main focus of the film. The viewer begins to see how these characters’ stories intertwine as time goes on, but we also begin to see that someone is keeping a secret that remains hidden from the viewer. This mistrust that grows between those trapped within soon reaches a tipping point where the bitter fight for control begins. This is where the violence that is associated with Tarantino first introduces itself.

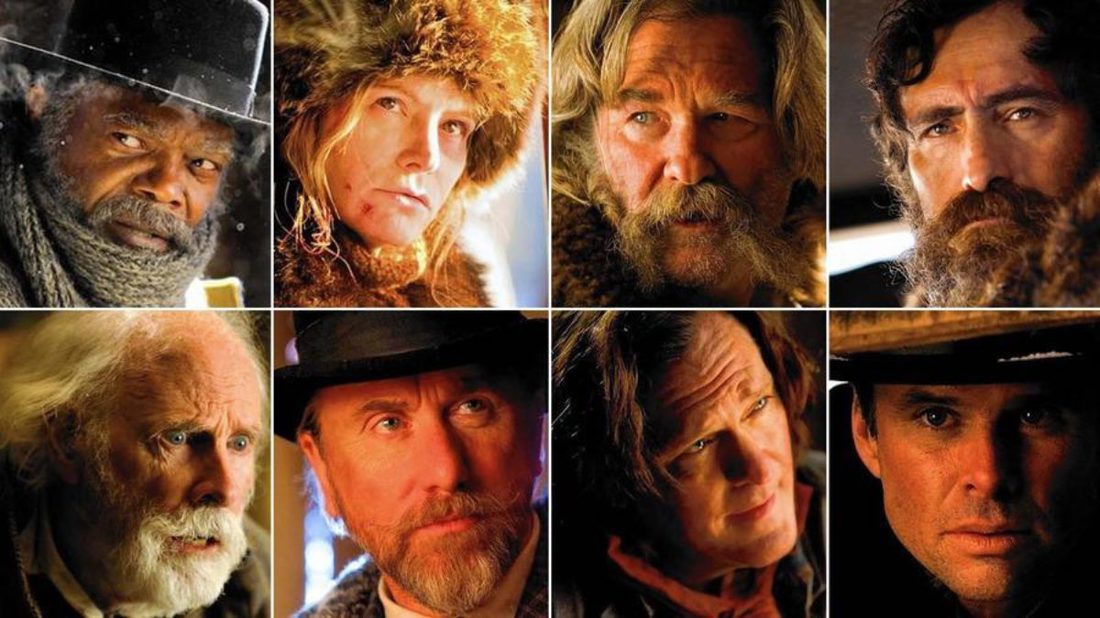

Just like the dialogue and writing of a story, another motif that many associate with Tarantino is violence. One thing that may shock some is the incredible lack of violence of the first half of the film. Violence permeates every Tarantino film, as if his fascination with blood and gore will never fully be satisfied, no matter how hard or how much violence he shows us on screen. Although, there is more to the violence than what we see on screen, there is also the violence that comes from the dialogue. Between what we see and what is heard there is no limit to the amount of violent content that is shared with the viewer. Asbjorn Gronstad notes that, “By isolating violent film segments, by ignoring contextual information, and by placing subjects in viewing situations that are highly controlled, empirical and sociological approaches reveal a disheartening illiteracy as regards the architectonics of cinematic perception. A mere enumeration and classification of the different types of violent action found in a fictional text – be it a Tom and Jerry cartoon or a Tarantino movie – are on the whole insignificant for an adequate understanding of screen violence” (Gronstad, 29). This implies that there is a large array of violence that viewers encounter within their lives and Tarantino is just the tip of the iceberg. These films though give us the opportunity to look at violence in the way Tarantino presents it to us, and in the case of The Hateful Eight, it is violence wrapped in masculinity. This issue of masculinity is one that has always existed in film, and has been a fascination of Hollywood cinema for over a century. Tarantino has explored the idea of gender and violence extensively. One of the surprising aspects of Tarantino’s career is how he has written and directed violent roles for both men and women, allowing both genders to express violence on screen. In Hateful Eight, Tarantino revisits his earlier work by bringing an ensemble of male actors all fighting to be on top. These violent characters have also proposed interesting new ideas of how we see the men who commit violence. In Hateful, there are many men played by many famous actors that have all come together. In recent years, there has been a rise in films of multi-protagonist men committing these horrendous acts. Film theorist David Greven has claimed, “In several distinct treatments of recent years, masochism has been valorized as a male subjectivity that defies traditional masculinism. What I wish to suggest here is that, despite the valorization of masochism, it is a mode that often makes a highly unsatisfying contribution to the resistance of masculinist oppression” (Greven, 48). This all ties into the area of gender study within film. Masculinity can be understood as the opposite of femininity, both inhabiting separate ends of a spectrum. This is a spectrum that Tarantino likes to play with, usually by taking women and introducing them to the world of violent masculinity. In films like Jackie Brown (Tarantino, 1997) and Kill Bill Vol. 1 and 2 (Tarantino, 2004-05) Tarantino introduces us into the world of powerful women that break barriers and enter the world of hyper-masculinity despite Hollywood’s fascination with shielding female characters from breaking masculine barriers. Not to say that there is a lack of powerful women in cinema, but the films of Tarantino thrust these women into the fast lane of murder, greed and gore. Tarantino does not hold back when it comes to allowing each character to enter the world of hyper-masculinity. This is the case for the characters in Hateful Eight. Each character brings about a different aspect of typical perception of masculinity. When examining John Ruth, we can get a clear look at who he is early on. He comes off as a gentleman bounty hunter that follows a code of honor; although early in the film see just how far he is willing to go to express his dominance over others. While riding in the wagon, Domergue is speaking to Warren, at which point Ruth strikes her in the face and says “When I elbow you real hard in the face it means shut up” (Hateful Eight). This act of violence that Ruth commits against a female gives the viewer their first glimpse that will continue throughout the film; “graphic violence evokes mere aggression rather than pity and fear” (Gronstad, 34). There is very little violence that happens offscreen in this film; Tarantino makes note to go out of his way to show nearly each and every act of violence that a character has committed. This is most apparent when we meet the one who is perhaps the most violent character in Hateful Eight.

Major Marquis Warren is quickly revealed to be a man of violent and calm demeanor. From the simple dialogue between these various characters we quickly learn that Warren has done nearly every horrific thing one could think of. In his early conversations Warren reveals how he escaped from a confederate prison by burning it down. He also goes into his history as a bounty hunter that has yet to be stopped by those who come searching for him. One of the most violent parts of the film comes from Warren telling the old confederate general Sandy Smithers (played by Bruce Dern) how his son died when he came to collect on Warren’s bounty. This scene is not explicitly violent in terms of blood or gore but instead we are shown the sexual violence that Warren has committed against the general’s son. Warren tells of how the son of the general went looking for him, but all he found was pain, suffering and death. Tarantino shows us through flashback with narration from Warren what happened to the man who came looking for him. For the first time in the film we are able to see the line crossing into hyper-masculinity in which there are no limits to a man exerting his power over another. Many of Tarantino’s films have characters such as these, men who will go to any length to show how their power over others is absolute. Warren is this character in Hateful Eight. He goes to extreme lengths and plays almost Machiavellian games with those around him to show his superiority. Sarah Eschholz and Jana Bufkin state “Crime as an alternative means to accomplish "masculinity" may be reinforced by media depictions of masculine characters using violence to solve conflict” (Eschholz & Bufkin, 659). No matter what got him there we see Warren using violence to get out of almost all situations. As though he was born into the violence that he revels in, Warren will go to any lengths to show his superiority over others. Still, there are questions over how the link between violence and masculinity is truly represented within the film. There is a character in the film that is always present but never speaks - yet it is the ultimate tool of masculinity: the gun. Guns are ever present throughout the film as they are in any western or any other action film. The presence of the gun has always been a staple in every western from the films of John Wayne to Clint Eastwood, the gun provides a very specific purpose to the plot of each of these films. When looking at the films of Eastwood, Karen Hoffman made several observations of the role of guns in his films, one of which stating “the gun that is so prominent in Eastwood’s early films and that becomes, throughout Eastwood’s career, an emblem of masculinity, an instrument for courageous self-defense, and an apparatus for enacting retribution is in Gran Torino cast aside in favor of a heroic act of self-sacrifice. Honor is shown to be compatible with a nonviolent response” (Hoffman, 150). These weapons have become a symbol of masculinity that has the ability to bring death but also redemption. This tool is not used in this manner within Hateful Eight; it is clearly made out to be the harbinger of death. It is a tool to extend one’s fist and keep control over those around him. Tarantino uses the gun not as a tool for defense or retribution that Eastwood did; instead it is a means to flex the hyper-masculine muscles that all these characters posses. The gun has a very specific role, unlike most other films, where most other films dare not to go, that is the realm of violence sadism and thirst for control. Tarantino reminds us of the destructive power the gun has and how easily it can calm, tame and conversely bring about the ultimate acts of hatred. Of course there are the violent tendencies of the characters, but what is Tarantino trying to say by combining an all-male cast with one female at the center of the entire plot? This structure leads to a great reveal that another extremely masculine character is that of Daisy Domergue. After appearing in a role as a victimized woman being brought to hang by her captor for the crimes she committed, we learn that she is just one of the masterminds that lead to the downfall of those in the cabin. Sigmund Freud and Laura Mulvey both wrote of the idea of the fetishized female figure. This theory can extend into the view of violence toward women and how that violence is fetishized on screen. The spectacle of violence toward women within Hateful Eight breaks the mold of a fetishizing view by explicitly showing the act of violence. There is no desire or want for the violence to ensue like one would perhaps from another film that may not directly show the violence or treatment of another. This is the gift that Tarantino brings to the screen, it is one in which all characters are brought to the same level of despicability that allows the viewer to comprehend the violence on screen without fetishizing a character based on their gender. This is one of the areas where Tarantino breaks the mold of his own films, keeping the viewers on their toes. There are other Tarantino films in which women are fetishized and made to be objects of desire. One other tendency is brought to light by John Cavallero as he discusses this film violence by saying “Sometimes Tarantino uses violence to advance his thematic concerns or implicate the audience in the on-screen action. Many of the most violent scenes in his movies are not shown at all. They occur in the minds of viewers when the camera pans away from police officer Marvin Nash (Kirk Baltz) while Mr. Blonde/Vic Vega (Michael Madsen) slices off his ear, or when viewers turn away themselves as Vincent Vega aggressively plunges an adrenaline shot into an overdosing Mia Wallace’s (Uma Thurman) heart” (Cavallero, 134). This, again, is not the case with Hateful Eight, in which much of the violence is depicted with great detail. The film contains several shootouts or instances of a character dying when the camera does not cut away but instead lingers on the act of killing for several seconds show it is great detail. There are other acts, such as the body of John Ruth being shot and maimed over and over by the surviving members of the group. We witness all of this violence as it occurs; it may happen to someone who is already dead, but the viewer still witnesses the spilling of blood and the tearing of flesh in a way that is almost animalistic. There is a contradiction that Tarantino includes in this film that distinguishes it from his others, and that is his willingness to break the mold of his usual style in a way that simultaneously adheres to the visual imagery that reminds us so well of his early work.

One of the captivating pieces of the film is the genius use of masculine drama to create tension for the viewer. The action is small throughout the film, yet the eye can’t be taken away from the screen. This comes from the masculine dialogue between the characters that leads us to feel as though anything could happen at any time. Two thirds of the film is spent with relatively no violence of location change. We sit in the same cabin and watch as conversation unfolds. The action is small, yet the amount of adrenaline begins to pump fast and fast as we move into the film. This is due to the tension that has been built by the sense of impending doom that builds more and more, faster and faster as the film progresses. An overall sense of ease comes from the first gunshot being fired. It is something the viewer spends the entire film waiting for. The buildup is almost unbearable; Tarantino knows this and toys with this idea until the audience sees the blood begin to spill. There is much technique that goes into leading the viewer to the point where they are ready and willing to see the violent spectacle unfold before them, the key to this is suspense. There are instances where one expects a fight to break out or shots to be fired but the hesitation lets the viewers’ desire for the gore build to a tipping point, as if we spend the first one hundred minutes riding to the top of a roller coaster waiting for the first drop to come, and when it does, we only want more. Unlike other films, the use of suspense builds the viewer toward a desire for violence. In most cases, the use of suspense shows the audience that something bad may happen and prepares the viewer for the impending scene they may not want to see. After the long buildup and tension, it becomes something that the audience thirsts after, all due to the conversations within film. What much of the film comes back to is the use of language, the words that come to life on screen. These words are the last true form of violence that is seen, or in this case heard from the film. The use of typical modern day profanity may be little, as the film is set in the west during the late 19th century, but there comes a form of violence from the use of racial and ethnic slurs that flow throughout the film. The use of racial slurs has become another well-known aspect of Tarantino, as he does not hold back in his writing and keeps it true to the character. When asked about the racial slurs for his characters in Reservoir Dogs, Tarantino said “ The thing is, do I think these guys are true racists? No. I just think they’re a bunch of guys getting together and talking a lot of shit. There’s a difference there. Do I think, you know, when Mr. White says a couple of things in the movie, do I think Mr. White thinks that blacks are like lesser human beings than him? No, I don’t. The main thing these guys are coming from is that they don’t look at blacks as professionals in their job, alright. They rob liquor stores. Now if there was like a black guy, say, a gunman that they trusted, they’d be different” (Cavallero, 142). This statement is still true for the characters within Hateful Eight. They spoke as though they were true to their time. Many of these characters fought on opposing sides of the Civil War, and there was no civility for the treatment of Black or Mexican Americans following the war. The film holds true to its time, even though it may be jarring for viewers to hear so many slurs used in one film. These prove to be a constant reminder of the state of the characters’ minds and their shared hatred for each other. The more slurs a character uses toward another shows the amount that they like each other, as is the case with Ruth when he strikes Domergue for using a slur against Warren. This is the last aspect of violence that the audience encounters other than the physical on screen. It serves the same purpose as the physical violence, which is to shock and bring the viewer into the claustrophobic world before them. The use of the ‘n word’ in a film is not something done lightly, it is usually something that in the case of Tarantino’s films is to stress the fact that “the racial identity of the characters who use the word (or the authors who write it) significantly affects the word’s context and therefore its meaning. Historically, whites have used (and some continue to use) the word to enforce racial hierarchies” (Cavallero, 142). The words used do change with context, and, in the case of this film, the character context is several people filled with hate trying to show their dominance. All of this violence has a purpose, or so Tarantino likes us to believe. It is possible that a version of this film could exist with little violence and be a much shorter affair, but that’s not how Tarantino works. There is a direct correlation between violence and masculinity in the various films of Quentin Tarantino, which reach a tipping point in Hateful Eight. Truly, this film is the most extravagant and violent of all the films over the director’s two-decade career. Does it mean that the violence will continue in future films? Not necessarily; while the amount of violence and masculinity has grown over the years with the films that Tarantino directs most of this has come from the cultural context for the time period for which the film was written. What the viewer must come to terms with while watching Hateful Eight is how much of this combination between male bravado and violent outcomes they are willing to accept. It is not every day a film like this comes along, and it provides a good opportunity for humans to embrace their more primal, animalistic sides that, at times, hunger for the violence that life may offer. Can this idea be considered radical? Yes. Is it one of the ways Tarantino helped build his career? Of course. Tarantino and violent masculinity go hand in hand, and films like this prove it. All we can do when watching a Tarantino film is sit back and enjoy the ride we know we’re about to go on. Works Cited: Hoffman, Karen D. “Giving up the Gun: Violence in the Films of Clint Eastwood.” The Philosophy of Clint Eastwood, edited by Richard T. McClelland and Brian B. Clayton, University Press of Kentucky, 2014, pp. 131–156, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hk087.10. Grønstad, Asbjørn. “Screen Violence: Five Fallacies.” Transfigurations: Violence, Death and Masculinity in American Cinema, Amsterdam University Press, 2008, pp. 25–62, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n1k3.6. Greven, David. “Contemporary Hollywood Masculinity and the Double-Protagonist Film.” Cinema Journal, vol. 48, no. 4, 2009, pp. 22–43., www.jstor.org/stable/25619726. Cavallero, Jonathan J. “Quentin Tarantino: Ethnicity and the Postmodern.” Hollywood's Italian American Filmmakers: Capra, Scorsese, Savoca, Coppola, and Tarantino, University of Illinois Press, 2011, pp. 125–150, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1xch6p.9. "Quentin Tarantino, Spike Lee, Violence and Racism in The Last Days of Obama." The Artifice. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2017. https://the-artifice.com/quentin-tarantino-spike-lee.../ Eschholz, Sarah, and Jana Bufkin. “Crime in the Movies: Investigating the Efficacy of Measures of Both Sex and Gender for Predicting Victimization and Offending in Film.” Sociological Forum, vol. 16, no. 4, 2001, pp. 655–676., www.jstor.org/stable/684828. |