A Separation: Exploring Class, Marriage, and Morality Through Iranian CultureBy Ben Becker Asghar Farhadi’s drama, A Separation, was without a doubt a successful film. It was the first Iranian film to win a Golden Bear Award, and currently sits with a 99% rating on Rotten Tomatoes and an 8.4 user score on IMDB. So what exactly makes the film work, and why is it resonating so well with its audiences? One could point to the fact that it is simply a well-made and cohesively told story, but the answer is a lot deeper than that. It is because the film touches upon several themes and issues that any audience member can relate to regardless of their background. What makes it feel fresh to so many, however, is how it uses Iranian Culture to explore these topics in a manner that is unfamiliar to anyone outside that country, and provides the audience with a new way of viewing the situation.

The first theme presented in the film is the dynamics of marriage and the relationship between men and women in Iranian society. The movie begins with a meeting between main characters, Nader and Simin, and a magistrate discussing the possibility of divorce. Simin does not wish for her family to remain in Iran, but Nader believes that he needs to stay and care for his father, who has Alzheimer’s. While the viewers may find themselves agreeing with one character’s reasoning over the other, they are both portrayed in a way that allows one to be sympathetic towards both sides. This is the area from which the dramatic heft of the film is primarily derived. Obviously, this situation serves as a backdrop to drive the emotional struggle between the two, but also informs the viewer of the complete dominance that men possess in Iranian society and how widely accepted it is. In the opening scene of the film where Nader states that he is unable to leave Iran because he cannot abandon his father, it is a valid motivation that the audience can most likely identify with, but the real intention of his side is to portray the way Iranian government favors one sex over the other. Because of Nader’s position as the husband in the relationship, the law sides with him. Simin, while disappearing off-screen for a significant amount of time in the movie, also presents a strong viewpoint that is comparable to Nader’s, but meets great oppression when trying to obtain it. Her primary motivation for wanting to leave Iran stems from the oppression that women face there, and that she does not want her eleven-year-old daughter to have to grow up in that environment. When Simin makes her claim to the magistrate, she says that she would rather her daughter “not grow up in these circumstances.” When the magistrate asks what circumstances she is talking about, Simin does not give an answer, because none is necessary. The low position of women in their culture is such common knowledge that it needs no explanation in common conversation. The film uses the conflict to commentate on the male dominance in the Iranian culture. Despite the formalities that are given to discuss the issue, Simin’s attempts at obtaining a divorce are never taken very seriously by anyone outside of the family. She is belittled and is only granted the separation from the magistrate because Nader becomes irritated and agrees to it. The difficulties that Simin faces in her situation serve to illustrate the male-driven politics that run throughout Iran as well as the subservience that women are expected to accept in that society.

There is also a third party as well, which is that of Termeh, the daughter. Termeh is an interesting character in that she essentially serves as the viewpoint of the audience. As the sides are not presented in black or white, but rather in a sort of gray area, the audience is meant to feel split and unsure of which is the right side to take. Termeh is the representation of this feeling in the story, stuck between the two most important people in her life who are currently in opposition of one another, and finds herself unable to affect the situation in any meaningful way, due to her position as both a child and a girl. Therefore, she can only attempt to solve the problem in small incremental ways. She initially makes the decision to stay with her father, but it turns out to be less of a definitive choice as it is a method to bring her parents back together. In the end, however, her results prove fruitless as she is and has no real power in the situation. She is only presented a choice in the matter when Nader and Simin allow her one in the final scene. We are not given an answer to what decision she made, and are instead left hanging to make our own prediction as to with which parent she will choose to stay. The harsh separation between men and women in Iranian culture can also be seen in the relationship between the couple of Razieh and Hodjat. Their story begins when Rozieh accepts a job from Nader to look after his father while he is out working during the day. When Razieh finds the job too overwhelming, she attempts to convince her husband, Hodjat, to come in and take her place. However, it is revealed that Razieh had not told him that she had already been performing the job. This is because in Iran it is illegal for a woman to accept work without her husband’s permission. As the audience, this scene served to be our first moment of suspicion at her character’s actions and motivation, as well as educate us as to the true dynamic between spouses in Iranian society. The second major theme of the movie is that of social class. The main events of the story revolve around the conflict that occurs between Nader and Razieh and the possibility of him killing her unborn child by accident. When Nader becomes angry with Razieh for leaving his father unattended, he throws her out the door in a temper when he knows she is pregnant. While the actual events that transpired would have been enough, a prime factor that drives this confrontation comes from the fact that Nader belongs to the upper-middle class, while Razieh is much lower on the social ladder. While the conflict serves the purpose of furthering the characters and drama, it also acts as an insight to Iranian law and politics. When Razieh and her husband take the issue to law enforcement, Nader is given time in prison if he is found guilty. However, the time he faces is only the minimum amount, despite the fact that his crime is second-degree murder of an unborn human being. This is because in Iran, murder is viewed as a private crime. It is not a wrongdoing against God, but rather against people. There is even an option for the guilty party to pay compensation to the victim’s family as an alternative punishment, which is later revealed to be Razieh’s real intention behind her accusation. Due to her social standing and her husband’s debts, she saw the situation as an opportunity for financial gain.

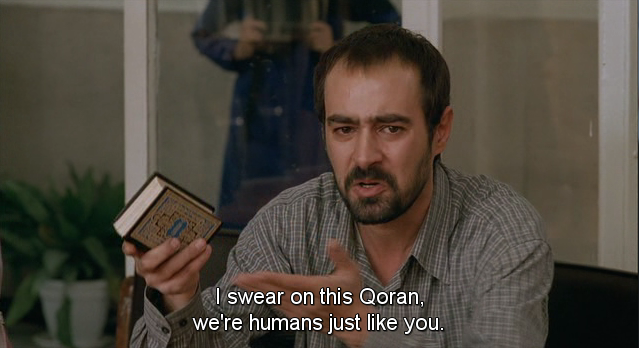

Farhadi makes a point to emphasize disrespect that exists between Nader and the husband, Hodjat, in the film as well. On the surface, it will most likely appear to be a result of the conflict over the death of the unborn baby, but it also speaks to the deeper political themes on which the film is commentating. Nader is of the upper-middle class. He is fairly wealthy and more civilized in public conversation. Hodjat, belonging to the lower class, is the exact opposite of this. He’s short- tempered, deep in debt and holds little influence in society. If the two men had belonged to the same social class, chances are they may have handled their encounters in a completely different manner. Nader observes their social standing and writes the conflict off as being beneath him, as can be seen from his exasperated attitude throughout the film. On the other end, Hodjat looks at Nader as someone higher on the social ladder and views him as being very bigoted, and is outraged that the loss of his unborn child is being taken less seriously than the mistreatment of Nader’s father. The way the characters view each other in this situation provides commentary into the way the people of the lower class are portrayed in Iranian society. In said society, there is an idea that has been reinforced by the wealthy that the poor are dangerous. It is because of this idea that the underprivileged find a great amount of oppression. You can see this theme present in the way Hodjat is viewed by the other characters. Simin sees him at Termeh’s school and believes that her daughter is in danger because she assumes Hodjat to be dangerous. The others also assume that Hodjat might actually be the one responsible for his wife’s miscarriage. Due to his social standing, he is assumed to be an abusive husband that may have killed his unborn child through physical violence directed at his wife. All of this serves to reinforce what the view of the lower class was at that point, providing subtle commentary on the issue in the background of the central conflict. The third major theme of the film is that of honesty and basic morality. The central conflict of the film is essentially a vehicle to explore the ethics of these characters and Iranian society as a whole. While one side may have technically been in the wrong, there are several factors to the situation, which show some form of moral failings from each side. All of these characters are faced with some sort of moral decision at some point in the film. One side is later revealed to be considered morally in the wrong, but the film provides enough of their motivations and actions to make both ends of the conflict slightly sympathetic, and also show that neither one of them is completely blameless. Despite the fact that Nader was not actually at fault for the death of Razieh’s child, he himself does believe that there is a possibility that he was to blame. When Termeh asks him whether or not he knew that Razieh was pregnant, he admits that he overheard her mentioning it in the dining room. He justifies being untruthful with the fact that he would be unable to provide for his father and daughter if he were in prison and cannot afford to admit his guilt. We even see Nader investigating whether or not it was actually possible for him to push Razieh in such a way that she would fall down the stairs, revealing his desperation to prove to himself that he wasn’t guilty. But when faced with the fact that he may be responsible, he does eventually meet with the couple to reimburse them for his actions, making the moral choice to do the right thing and accept the consequences. The ideas behind basic morality in Iranian society actually become the deciding factor in the film’s climax. At the end of the film, Nader meets with Razieh and Hodjat to discuss the terms of their settlement. Before his confession though, Nader asks Razieh to swear on the Qur’an that her claim that he killed her child is true. To us, as an outside audience, our solution for the scene would probably seem simple. Anyone unfamiliar with Iranian culture would most likely assume that all Razieh would have to do to win the case is lie, since she has been lying about the cause of her miscarriage the entire film. However, she can’t bring herself to do it, because her steadfastness in her beliefs prevents her from taking things that far. The strong dedication to religion that is present in her culture is shown at multiple points, most notably when Razieh calls a religious hotline to ask whether or not it was morally excusable to change Nader’s father. We can see throughout the film that Razieh felt her need for compensation justified the lies that she was telling, but the moment her faith was brought into the situation, she couldn’t bring herself to betray it. Seeing how uncivilized and ill-tempered Hodjat has been throughout the duration of the movie, a viewer may feel as though he may not share her sentiment, but when Razieh gives him the truth in a back room, he becomes enraged, not at her reluctance to lie, but at the fact that they are now in, what they see as, an unwinnable situation. He completely gives up on the fight as well because his beliefs also take precedence over compensation. The end confrontation also gives a fascinating insight to the morality of the characters of Razieh and Hodjat comparatively. Despite his harsh demeanor, Hodjat is revealed to actually be the one with the greater sense of morals. Throughout the film, we see Hodjat harassing Nader’s family, but it was all in service of what he believed was justice. Then, when he finally learns of Razieh’s dishonesty, he abandons his side of the argument, realizing that he has been in the wrong. He even hits himself out of frustration, and doesn’t lay a finger on his wife, which provides a stark contrast to the abusive husband we had suspected him of being throughout the film. Razieh, in direct contrast with her outward appearance, is the one who lies in order to gain reimbursement, even though such action can be seen as immoral. Until her faith and the Qur’an are brought into the conflict, she fully intended to force Nader to pay for something that wasn’t his fault. The majority of the film had set up Hodjat to be an unhinged, possibly abusive husband, but is revealed to have a pretty decent sense of right and wrong. On the other end, Razieh is portrayed as extremely timid, but is shown to have ulterior motives to her actions. The film makes a point to illustrate that outward appearances can often be misleading, as well as showcase the ways that human beings will often attempt to justify their own actions to convince themselves that they are the ones in the right.

When analyzing Asghar Farhadi’s drama, A Separation, and what makes it such a critical success, it is important to look beneath the surface. The central conflict is extremely compelling on its own, but it is the added subtext and complexity that make the film resonate so well with audiences. Farhadi uses the primary characters and their confrontations to commentate on Iranian culture and society. While everyone can relate to subject matter such as marriage, social class structure and basic human morality, seeing it in a context that an outside audience may be unfamiliar with gives the film an air of freshness. That is what makes A Separation so successful. Works Cited: Burke, Joseph. Rediscovering Morality Through Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation. Senses of Cinema, 2011. Cheshire, Godfrey. Scenes from a Marriage: Iranian Cinema breakout Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation and its Intricate Emotional Standoffs. New York, Film Society of Lincoln Center, 2012. Haqshenas, Saleh. Badiei, Sediqeh. Narmani, Hamid. Iran's Perspective: A Deconstructive Analysis of "A Separation Movie" Through Application of Binary Opposition. The International Research Journal “International Researchers”, 2013. Mandell, Zack. ‘A Separation’ Reflects on Iranian Culture. Cultural Weekly, 2012. |